On a typical day in the lab, Clemson University graduate student Mel Walker might analyze blood and tissue samples from sharks caught off South Carolina’s coast or water and sediment scooped up from nearby estuaries.

It’s not what the second-year master’s student in environmental toxicology pictured when she decided to return to school after working in the finance field.

“I’ve always appreciated sharks, but it was actually my advisor who encouraged me to take on an existing shark project on the west coast with a small grant she received from the Save Our Seas Foundation and develop my own project on the east coast,” she said. “I never imagined I would be working with sharks when I decided to go back to school, but it has been an unforgettable experience.”

Walker’s research examines how pollutants like mercury and PFAS — short for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances often called “forever chemicals” — accumulate in coastal shark populations. These chemicals are known for their persistence in the environment and their potential to cause health problems in wildlife and humans.

In decline

“Most shark populations across the world are in decline, and it’s from a variety of factors — extreme weather, climate change and overfishing. We want to know how much pollution could be contributing to those declines,” said Kylie Rock, a toxicologist and assistant professor in the Clemson Department of Biological Sciences and Walker’s advisor. “Specifically, we want to know whether dietary preferences contribute to the accumulation of contaminants and maybe put some species at more risk than others.”

Each field season (mainly in spring, summer and fall), Rock and Walker join South Carolina Department of Natural Resources biologists on survey boats, using a combination of gill nets, longlines and drum lines to catch two species of sharks — finetooth and sandbar. Both swim in the same waters but eat very different diets. Finetooth sharks feed mainly on small Atlantic menhaden, while sandbar sharks are less picky.

The dietary difference could make a big difference in contamination.

Sharks are caught, and blood and tissue samples are taken before they are released.

Samples show accumulation

“Blood samples capture what’s circulating in the body at the time, and levels can be affected by how much time has passed since the shark last ate,” Rock said. “Tissue samples, which are taken from the muscle near the dorsal fin, provide a more long-term picture of the accumulation of the chemicals in their body.”

“We’re seeing higher mercury concentrations in larger and older sharks and in species with more varied diets,” Walker said.

“Sharks are telling us a story about our ecosystems and what we’re putting into them. If we listen to that story, we have a better chance of keeping both wildlife and people healthy.”

Kylie Rock, toxicologist and assistant professor in the Clemson Department of Biological Sciences.

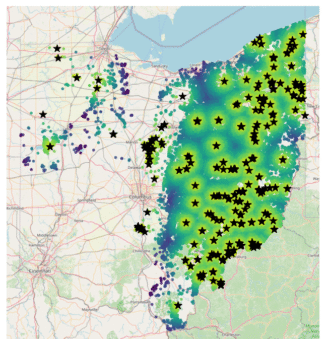

The researchers are also seeing elevated PFAS in South Carolina coastal waters and the estuary floor. Walker is working to test the shark samples for PFAS as well.

“Both may indicate bioaccumulation potential for both mercury and PFAS up the food chain, but our results are not finalized yet,” Walker said.

One estuary with no major industrial or other known pollution sources showed higher PFAS levels in water than more urbanized sites, which may indicate that unique characteristics of each estuary, such as water movement, may shape contaminant exposure more than proximity to pollution sources alone, she said.

“These pollutants don’t break down easily,” Rock said. “They can linger for decades and move through every level of the food chain, from microbes to top predators like sharks — and even to humans who eat seafood from those waters. Understanding which species accumulate contaminants most quickly could help refine federal seafood safety guidelines and support the development of better water-quality policies.”

Wider effort

The shark project is part of a wider effort in Rock’s lab to understand how chemicals affect both the environment and human biology. One research branch investigates endrocrine-disrupting chemicals and reproductive health, while another focuses on ecosystem-level contamination.

Many of the Rock lab projects build upon each other, integrating different aspects of ecosystem toxicology research. One graduate student is working to develop models to predict contaminant levels in shark organs, while another is studying whether certain bacteria in estuaries might break down PFAS, which could be key to potential future cleanup strategies.

For Walker, the hands-on experience will be advantageous for her future career.

“I may not become a marine biologist per se, but this project has helped me build skills in sample collection, testing and the ability to look at different aspects of an ecosystem, such as sediment or soil, water and species at all levels of the food chain from microbes to predators. That will help me in a role such as environmental risk assessment of specific sites identified for construction or building, or alternatively as sites in need of cleanup,” she said.

“The Upstate region in South Carolina is growing rapidly, and I would like to play a bigger part in helping our local community expand in a safe way so that we can all enjoy this beautiful area and all its natural wonder to its fullest.”

Rock said that sharks are uniquely charismatic animals that naturally capture public attention, an interest scientists can leverage to communicate broader environmental messages.

“Sharks are telling us a story about our ecosystems and what we’re putting into them,” she said. “If we listen to that story, we have a better chance of keeping both wildlife and people healthy.”