On Feb. 28, 2021, the Call My Name (CMN) project hosted its second gravesite tour.

The tours are designed to inform Clemson University students, faculty, staff and others about one of the most important African American burial grounds in South Carolina while also honoring the African American contribution to the University’s history.

The first tour was held October 2020.

Participants toured the Woodland Cemetery, which serves as a burial ground for the Calhoun family and for faculty members of Clemson University. The cemetery also serves as the final resting place for 667 unnamed persons who are believed to be African Americans who worked on Fort Hill Plantation as enslaved persons, sharecroppers, convicted laborers and wage workers.

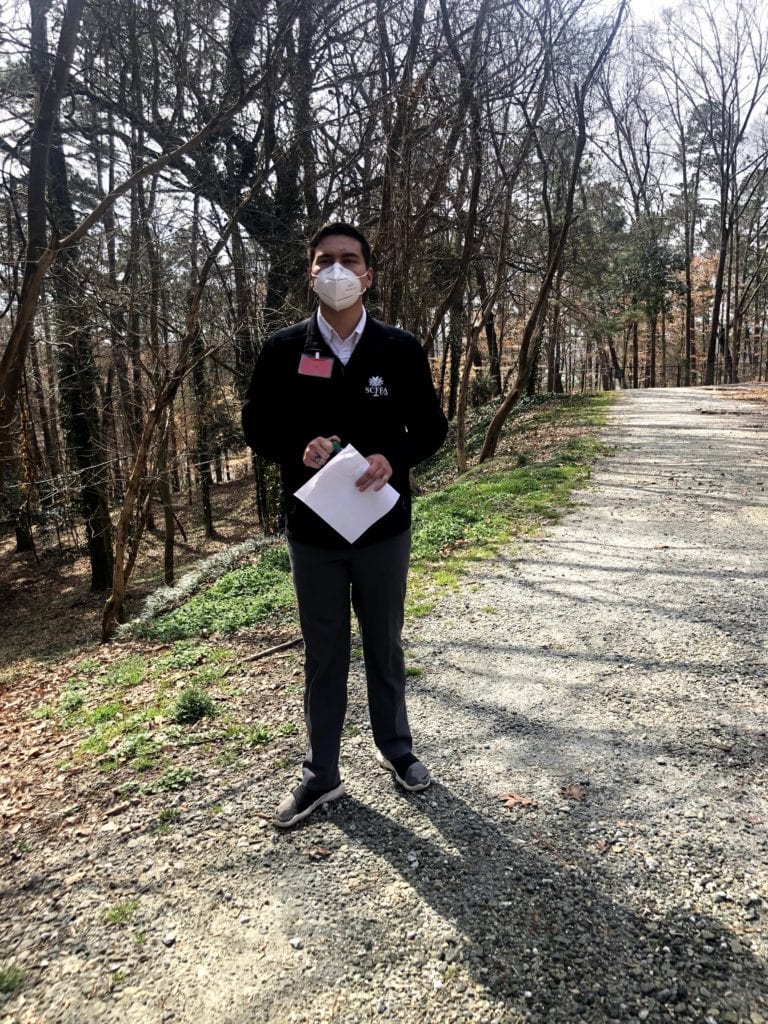

Many students volunteered to helped with the tour. Among them were Nathan Kilcoyne and Jake Faulkner, students in Clemson’s College of Agriculture, Forestry, and Life Sciences (CAFLS).

Kilcoyne, a sophomore Food, Nutrition and Packaging Science major from Greenville believes it is important to tell Clemson’s complete history even if it has some warts.

“This project is really important to me because I believe it is my duty as a Clemson student, resident, and White ally for equal rights to know the Black history that lives under this gravesite,” he said.

He also believes that you can’t look at the present, without looking at the past.

“It is not until we examine the lives of those who came before us, such as the African Americans under those burial grounds that things can change for the better,” he said.

Faulkner is a junior Agricultural Education major from Indian Land, and he learned about the CMN project through an English class he took his freshman year. Since then, his interest never wavered and he felt that helping the community with the graveyard tour would bring something positive to the Clemson community.

“I decided to work with the Call My Name Project because I feel like it is making a positive difference on campus and in the community. I’ve always been a service-driven person and to be able to help with leaving that positive impact is one of the best things in the world to do,” he said.

Falkner believes that being a CAFLS student gives him a unique understanding of the project.

“I believe that as a CAFLS student, I have a different perspective and understanding of certain aspects of the project. For example, I know much more about the agricultural history that relates to and develops along with the stories of the many African Americans who worked hard on this land for so many years. Also, with my major being Ag. Ed., I feel very deeply connected with the roots of the university. This makes me feel such a greater connection to those who physically built this university from the ground up — all of the laborers who made me education possible from the very start,” he said.

Faulkner also believes that the tour is important because it reflects a lost narrative from Clemson’s history.

“CMN is very important to me because so many great important stories of great, important African Americans are so easily lost over time,” he said. “Not only are we learning about the history our great university and its roots, but we are honoring the legacies of those who worked so hard and deserve recognition, perhaps more so than many of the other people already recognized for their works,” he said.

With help from students like Kilcoyne and Faulkner, Rhondda Thomas, Calhoun Lemon Professor of Literature, faculty director and director of the CMN project, had first been made aware of the unmarked graves in February of 2020.

“I was angry when I learned that the African American burial site had been neglected, littered with trash and that the chain link fence that enclosed it was falling down, especially when the larger Woodland Cemetery was well kept and respected. I did not understand why Clemson allowed this sacred, historic burial site to fall into such a state of disrepair,” she said.

Once she learned about the horrific condition of the burial site, she and her team worked tirelessly to get the area cleaned up and restored. July 2020 through Jan. 2021, ground-penetrating radar tests were conducted, revealing more and more unmarked graves, and bringing the total number to 667. Each grave is marked with white and pink flags. Those that are under road or concrete are marked with a white circle with a pink dot in the middle.

Like Thomas, Faulkner realizes that the passing of history from one generation to the next is important.

“That’s the whole purpose of CMN. Passing these stories down and making it known who exactly provided the opportunities for us to be here today,” he said.

###

by Malaysia Barr, Junior, Communication ‘22

Get in touch and we will connect you with the author or another expert.

Or email us at news@clemson.edu