The Town of James Island estimates 17,000 pounds of fecal material were collected in the first year after its Pet Waste Station Program began, meaning roughly 8.5 tons were kept out of its picturesque coastal waters and marshes in Charleston County.

That, by virtually any measure, is a massive amount of poop.

But according to Public Works Director Mark Johnson, the program’s success has been built on anything but a load of bull.

“We have used the Clemson Extension and Ashley Cooper Stormwater Education Consortium materials and educational programs as the foundation for educating the public on these water quality issues,” Johnson said. “Picking up the poop, rainwater harvesting and storm drain medallion programs have all helped get the public interested in clean water around our island.”

Carolina Clear, Clemson Extension’s stormwater education program, works to educate the people of South Carolina on issues associated with polluted stormwater runoff and raise awareness of actions and behaviors that ultimately protect water resources.

More than half of the 75 Municipal Separate Storm Sewer Systems (MS4s) in the state partner with Carolina Clear to educate residents on matters such as pet waste, along with maintenance of septic systems, the potential of rain gardens to protect water downstream and the problems with putting fats, oils and grease (FOG) down the drain.

In order to address those problems, however, Carolina Clear first needed to identify them, and a big part of the process were statewide surveys in 2009 and 2013. A third iteration of the survey, conducted in partnership with survey company Responsive Management, began in 2019 with a twofold purpose: to gauge knowledge and behaviors related to stormwater and water quality across South Carolina and to measure the impact of Clemson’s Carolina Clear educational programs.

“We’re always sort of triangulating and getting that directive from other places, as well, but this is certainly a foundational component of how we decide to deliver information and what information we decide to focus on as it relates to stormwater and water resources in general,” Carolina Clear Program Coordinator Kim Morganello said.

About 2,000 South Carolinians participated in the latest survey, and the good news is the results show the state’s residents have increased their understanding of how their actions affect water quality in the state. Ninety-four percent of residents think clean water is very important to the state’s economy and 87 percent are concerned about pollution in their local waterways.

The survey also showed, however, plenty of educational work remains. For example, a frequent misconception is stormwater flows directly to a water treatment plant and is cleaned before being released into the environment.

But stormwater isn’t treated at all in South Carolina; it flows directly from the landscape into ditches and pipes and out into local waterways untreated instead. While 40 percent of those surveyed recognized that fact — a major increase over the 23 percent who knew that stormwater goes untreated in 2009 — it also shows a need to further increase awareness.

Those who participated in the survey, which focused on urban centers but included regional sampling across the state, were asked to rank the threats posed by various sources of water pollution, and one of the most common that ranked highly was industrial sites.

And that, according to Clemson University Assistant Professor Amy Scaroni, who also serves on Clemson Extension’s Water Resources Program Team, is another misconception that needs to be addressed.

“This is similar to what we’ve seen in previous surveys,” she said. “The problem with that is stormwater is actually the biggest threat to water quality across South Carolina. There’s this tendency to attribute pollution to things like factories and industry, and not to recognize the impact that residents themselves have on water quality through stormwater runoff.”

In reality, industrial sites are regulated point sources of pollution, which makes them easier to control due to constant monitoring, measurements and regulation — unlike stormwater pollution which runs from private properties and cannot easily be pinpointed back to a specific source.

“We call that non-point-source pollution,” Scaroni said. “That’s what we really have to manage, and that’s what we all have to play a role in preventing.”

When it came to behaviors, the survey attempted to ascertain if knowledge about stormwater pollution translated into taking actions that reflect that knowledge. The 60 percent of those surveyed who believed stormwater was treated prior to being released into waterways closely correlated with the 40 percent who said they had dumped something down a storm drain.

“Those sort of pair in that if you think it’s treated, you don’t feel so bad about dumping your paint wash or soapy water from washing your car down the storm drain, forgetting or not realizing that it’s heading right out to your local stream or creek,” Scaroni said.

Only 12 percent of those surveyed said they dump FOG down the drain, but even such a low percentage represents a big problem — clogging drains, causing sewage backups and many other issues with water quality.

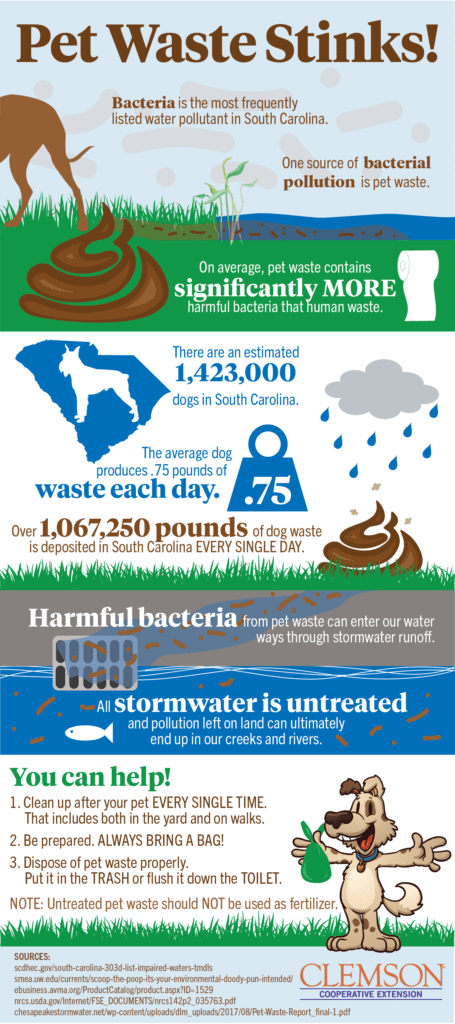

While 67 percent said they always picked up after their pets, showing state residents are taking that message to heart, bacteria remains the most common water quality pollutant in South Carolina, making it the biggest impairment in the state’s waterways.

“Picking up pet waste might sound like a small thing, but it’s extremely important,” Scaroni said. “It’s not just something you want to avoid stepping in, it’s a contributor to pollution in our local waterways. And bacterial pollution can lead to things like beach closures to swimming and closures of shellfish beds — because it is a health hazard.”

The most common reasons people did not pick up after their pets were: because it was on their property, a belief pet waste is biodegradable, inconvenience or lack of a place to dispose of it.

Such information from past surveys helped inform James Island’s Pet Waste Station Program, created after years of complaints about pets defecating in yards or owners putting pet waste bags in other people’s garbage cans.

A partnership with the James Island Public Service District, which collected the aforementioned 8.5 tons of solid waste from cans at seven neighborhood stations and three park stations in the town, the program has been a major success.

“This is fecal material that has been kept out of our coastal waters and marshes,” Johnson said.

And that’s the kind of impact Clemson Extension aims to make on a statewide scale.

“The majority of state residents visit beaches or spend time near water while hiking, hunting or walking in nature,” Scaroni said. “So, our waterways are really important and highly accessed and used by our residents, not just at the coast but across the state. This is important for the Carolina Clear program because it can help to identify target audiences for their messages.”

Get in touch and we will connect you with the author or another expert.

Or email us at news@clemson.edu