Their Clemson degrees and decorated U.S. military careers have spanned more than four decades and multiple continents. Most amazing of all, their lifelong friendship continues to this day.

George Bresnihan ’92 and Louis Mitchell ’91 were a couple of 9-year-old rascals when they first crossed paths on the suburban streets of the West Ashley area in Charleston, South Carolina, in the late 1970s. It was a time when parents of young boys bursting with energy could release them out into the community without fear, and it was pretty much inevitable the two would bump into each other. What wasn’t assured was a friendship that would endure 45 years and counting and carry them both to the highest echelons of military service.

As youngsters, they were outside constantly, tearing through the neighborhood on their bikes, playing basketball and football, or doing laps and finding friends at the local roller-skating rink.

“Sports, music and girls are what brought us together,” says Bresnihan, whose father, George was a veteran of the Vietnam War who retired from the Navy and then worked in the private sector. Bresnihan’s mother, Marguerite, taught high school for 30 years and is a fourth-generation Charlestonian.

“Most people who knew us back then will tell you if they saw one of us, they saw the other,” Bresnihan says.

“We were almost always outdoors,” says Mitchell, whose father, Louis Sr., was also in the Navy before becoming a nuclear machinist in the Charleston Naval Shipyard and whose mother, Wilma, worked as a civilian for the Air Force.

“Home video consoles had just started coming out,” Mitchell recalls. “George got really good on the Atari platform, and I was decent at Intellivision.”

When they outgrew kids games, they became entrepreneurs and teamed up to start a lawn-mowing business. They were 14.

Above: Mitchell (purple shirt) and Bresnihan reminisce on a basketball court that they used to play on as kids in their old neighborhood of West Ashley, Charleston.

In high school, they gravitated to community service and joined Civitan International, an organization of volunteer service clubs dedicated to helping people wherever the need arises.

Once, they challenged each other to try out for the school play, “My Fair Lady,” and got cast.

One night after rehearsal, feeling mischievous, they decided to play a game they called Fox and Hound with some friends on the way home, chasing each other through the streets in their cars. Mitchell and Bresnihan, still dressed in their Edwardian-era costumes, got pulled over by Charleston’s famous police chief, Reuben Morris Greenberg, the first Black police chief of Charleston, who took one look at them and asked what on earth they were doing.

“We said, ‘Uh, we’re in a play?’” laughs Mitchell. “He asked us what play, and when we told him, he started drilling us about the characters because he knew it! Since we were able to answer his questions, he let us go, and, man, were we relieved!”

Not all of their childhood memories are that comical. Bresnihan recalls an incident when the two worked at a fast-food restaurant and a deposit went missing. The owner immediately blamed his only two African American employees. The two were summoned to the police station, fingerprinted and then placed in separate rooms to be interrogated.

“These detectives came in and told me, ‘Hey, your buddy told us you did it, so what do you have to say for yourself?’” recalls Bresnihan. “I said, ‘I know he didn’t tell you that.’”

Meanwhile, Mitchell was in another room hearing the same lie that his friend had confessed to the crime and was not as restrained with his answer: “That’s a damn lie! He didn’t tell you that.”

The two were released, and the girl who stole the money was caught shortly after.

Looking back, the incident was just another bump in the road that didn’t stop their momentum.

Growing and going to Clemson: together

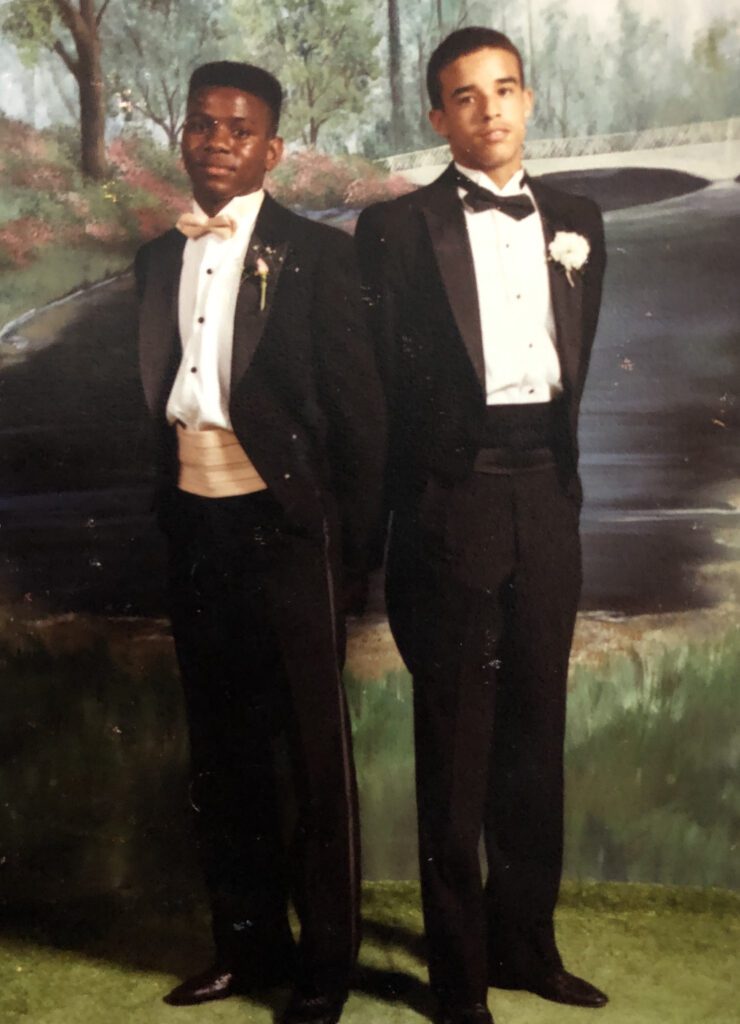

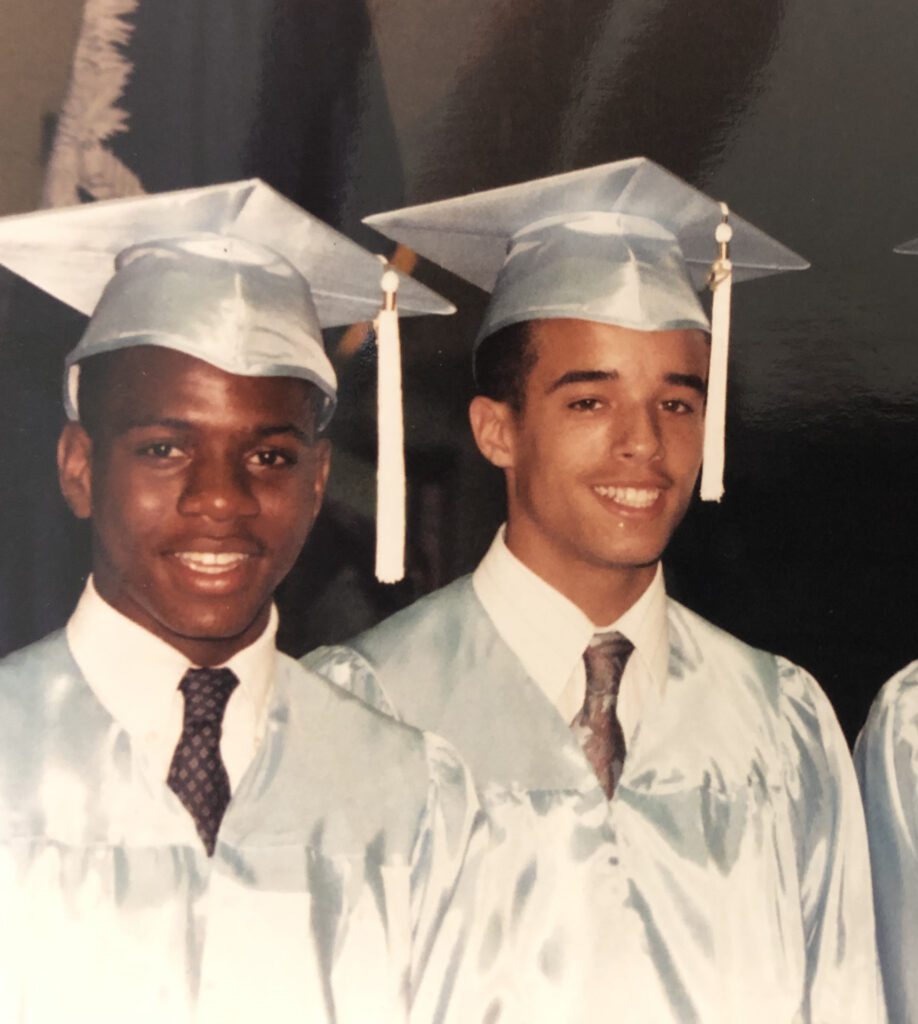

The two young men kept each other moving forward and excelled in school, and as the end of their senior year of high school came into sight, they started preparing for the next chapter. Once again, their teamwork kept them on the right path.

“We were underexposed,” says Bresnihan. “We consistently lacked guidance counselors or teachers providing us with college information. We often found ourselves among only two or three African American students in college prep classes, but when representatives announced workshops for African American students at Clemson in the summer, our counselors never presented the opportunity to us.”

So, when they were 16, they took it upon themselves to drive four hours north to South Carolina’s most prestigious institution of higher learning and sign up for a tour. It impressed them so much that they both applied and started their Clemson journey in 1987 straight out of high school.

Mitchell secured a three-year scholarship from the Army to attend Clemson’s Reserve Officer’s Training Corps (ROTC) program. Bresnihan signed up for the program, too, “to see what it was like.”

They moved into Johnstone Hall together as undergraduates and remained roommates for the next four years, eventually moving to Calhoun Courts and then an apartment off-campus. Mitchell completed the ROTC program, graduated with a Bachelor of Science in civil engineering in 1991, and was commissioned into the Army Reserve. Bresnihan left the ROTC program after two years.

“I wasn’t quite ready to make the commitment,” he says. He earned a Bachelor of Science in management in 1992, returned to Charleston, and spent 18 months working in the private sector before deciding he was ready to commit to something bigger than himself.

With his father’s encouragement, he applied for and was accepted to Navy officer candidate school and received his commission in 1994.

Giving back

Mitchell and Bresnihan are both proud Clemson Black Alumni Council members and teamed up with a group of fellow Clemson alumni to set up an endowment to help students find their way to college through the Clemson Career Workshop. The F.E. Brothers Endowed Diversity Scholarship was established to support the scholarship efforts of the Snelsire, Sawyer, & Robinson Clemson Career Workshop, a summer program designed to support the readiness of high-achieving students from diverse populations to enter college.

In the meantime, Mitchell was off to the races in two roles: as an Army Reserve officer and as an engineer for the North Carolina Department of Transportation. He would accomplish equal success in both. One of the benefits, he says, of being a “citizen soldier” is the opportunity to thrive in both military and civilian careers.

When asked why he didn’t choose the Navy like his friend, his father and his friend’s father, Mitchell is matter-of-fact:

“My dad was a nuclear machinist at the Charleston Naval Shipyard, and they would have family days there,” he says. “Going into those submarines was not my thing. Turns out I have claustrophobia, so the Navy was not for me.”

Above: U.S. Navy Rear Adm. George Bresnihan, director of logistics for United States Africa Command (AFRICOM), and U.S. Army Reserve Brig. Gen. Louis Mitchell, deputy commanding general for operations, 416th Theater Engineer Command, in the Upper Battery Park area of Charleston, South Carolina.

Life after Clemson: education and service

For the next 30 years, the two men would steadily climb the ladder of their respective services, always leaning on each other through the hard times, including multiple deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan for each.

Both men also continued their education with gusto; Bresnihan earned master’s degrees in business administration from Webster University and military strategic studies from the Air Force’s Air Command and Staff College, and Mitchell earned certifications as a registered professional engineer and a certified public manager as well as a master’s degree in strategic studies from the Army War College.

Serving with honor

Bresnihan and Mitchell have each served their country admirably for more than three decades, as evidenced by the piles of decorations they’ve earned:

Bresnihan’s awards include the Defense Superior Service Medal, Legion of Merit (two awards), Defense Meritorious Service Medal (two awards), Meritorious Service Medal (four awards), Joint Commendation Medal, Navy Commendation Medal (three awards), Navy Achievement Medal, and various service and unit awards.

Mitchell’s awards and decorations include the Legion of Merit, Bronze Star Medal; Combat Action Badge; Meritorious Service Medal; Army Commendation Medal; National Defense Service Medal; Global War on Terrorism Service Medal; Iraqi Campaign Medal; Army Service Ribbon, Armed Forces Reserve Medal (with “M” Device); and Overseas Service Ribbon.

When challenges presented themselves as they inevitably do in any career, each man knew his counterpart was just a phone call away.

“You always need a sounding board,” says Mitchell, who retired from the NCDOT after 29 years and now works as a senior vice president for Volkert Inc., a national engineering firm. “The military culture is what it is. Only people who are in it can really understand it. Having a comrade who can give you a different perspective and who understands the culture has meant so much. There was never any competition, only encouragement. When we misstepped, we would correct each other’s azimuth as colleagues and friends.”

Lifelong bonds: military, family and college

Today, the determined duo is closer than ever even though they live in different countries. Bresnihan is currently stationed in Stuttgart, Germany, with his wife, Janine, and Mitchell lives in Charlotte, North Carolina, with his wife, Karen, a fellow 1991 Clemson grad. Between the two men, they have five kids and three grandkids.

“Be sure to mention Louis’s daughter Karina just commissioned as a second lieutenant into the Army Reserve!” says Bresnihan, beaming like a proud uncle.

Both men wear stars on their shoulders: Bresnihan as a rear admiral in the U.S. Navy and Mitchell as a brigadier general in the U.S. Army Reserve.

“There are only 13 African American flag officers in the entire Navy,” says Bresnihan, currently the director of logistics for United States Africa Command (AFRICOM). “There are about the same number of African American generals in the Army Reserve. That’s improbable in and of itself, but if you take two little Black kids from the same neighborhood in Charleston, and fast forward 30 years, I just don’t know what those crazy odds are that we would both become one-stars. There are so many things that could have gone wrong.”

Mitchell says one thing they had in their favor was having a friend with the same ambition and work ethic making his way up the ranks right next to him.

“We both have a big group of friends, but then there are those few people you trust implicitly,” says Mitchell, currently the deputy commanding general for operations, 416th Theater Engineer Command in Darion, Illinois. “I know I can call Louis and vice versa if I need something. For instance, if Louis is spending time in Charleston and my parents need anything, Louis is there, and I don’t find out until afterward. My parents tell me, not him.”

Bresnihan said when he thinks about himself and his friend, he sees two young men who were hard workers and big dreamers who lifted each other. Not only did they work and play side-by-side through their childhoods, their young adult lives, and then at Clemson, but when it came time to pin on the ranks of general and admiral, each man acted as master of ceremonies for the other’s promotion.

“I would say that, in many ways, what motivated us was never wanting to disappoint each other,” Bresnihan says. “You never want to let your boy down. That translated directly to pride in each other’s accomplishments. When he made one star, that was it for me. I was fine if I didn’t get it because we’d already made it.”

U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM), headquartered in Stuttgart, Germany, is one of 11 U.S. Department of Defense combatant commands, each with a geographic or functional mission that provides command and control of military forces in peace and war. U.S. Africa Command employs the broad-reaching diplomacy, development and defense approach to foster interagency efforts and help negate the drivers of conflict and extremism in Africa.

The 416th Theater Engineer Command, headquartered in Darien, Illinois, is one of only two Theater Engineer Commands in the Army, providing technical and tactical engineer support to U.S. forces. The command has a national and global impact as it participates in humanitarian operations and joint training exercises throughout Europe, Central America, South America, Asia and the Middle East. Domestically, the 416th TEC trains and equips units and Soldiers in 26 states west of the Mississippi River.