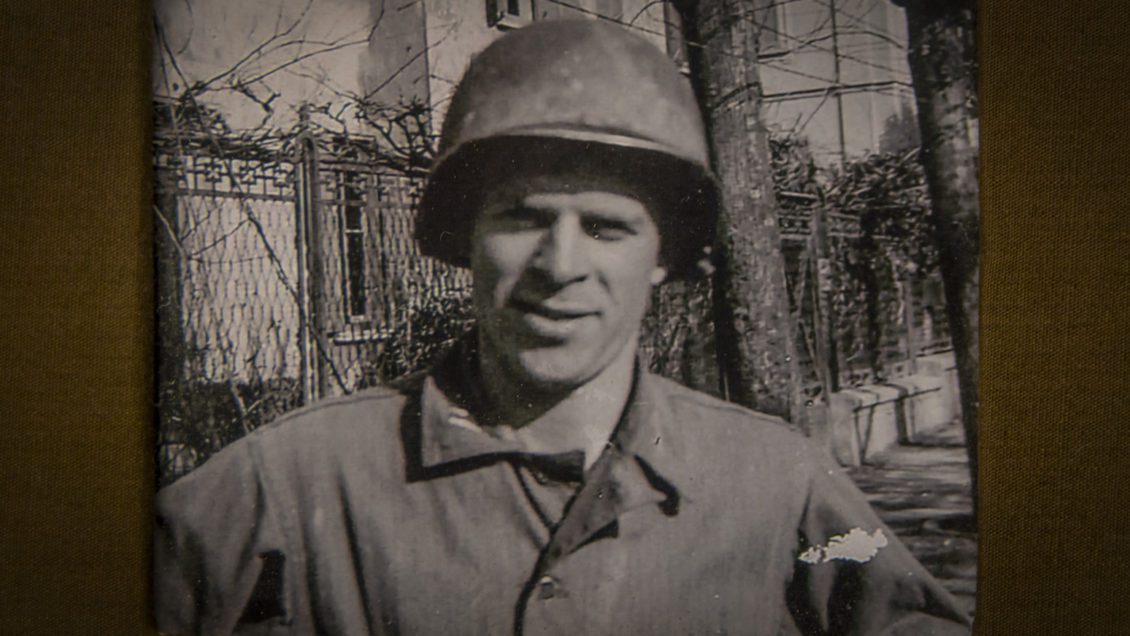

U.S. Army Capt. William Cline was a lot of things: husband, father, proud Clemson Tiger, war hero and – thankfully for future generations of Clemson students and researchers — a meticulous cataloger and avid photographer.

Several years ago, his son, William “Bill” Cline Jr., a 1970 Clemson graduate, discovered a stack of dusty boxes hidden in the shadows of his mother’s attic in their home in Greenville.

He dug through the contents of the boxes and pulled out one amazing discovery after another: his father’s Clemson graduation program, report cards, Christmas cards, a job recommendation letter from one of his father’s professors, World War II-era Clemson decals, military orders and two albums of letters Cline wrote to his parents from the battlefield.

Downstairs in the living room, two albums of photographs that had been resting on a shelf for decades took on a whole new meaning. They were full of pictures his father took while serving in Europe in World War II.

Put together, the collection is a remarkable archive of one of the most significant times in American history.

“It was kind of an accident,” Cline Jr. explained. “It had all been sitting right over our heads for 30 years after dad passed away.”

As a second-generation Clemson graduate, Cline Jr. spent his life filled with pride in his dad’s character and service to the nation, but the items inside those thin cardboard containers revealed a side of his father he had never known.

“I’ve always felt the story of my dad is very unique,” he said, “but it was very emotional to discover the whole truth of his service in World War II.”

William Cline Sr. was commissioned into the U.S. Army upon graduation from Clemson in May 1941. From there, he was sent to Fort Knox to train in tank tactics and mechanized warfare. In 1943, he was assigned to the 758th Tank Battalion, a rare all-African-American unit that was part of the fabled 92nd “Buffalo” Infantry Division.

At the time, the Army often assigned white officers to segregated units as company commanders. The Army had three segregated tank battalions in World War II: the 758th, 761st and 784th. By 1945, the 761st had African-Americans in most of its officer positions, while the 784th was led only by white officers. Officer positions in the 758th were split half-and-half, with the black company commanders commanding combat units while the white officers commanded service and administrative units. Cline was assigned to the 758th Service Company, which recovered damaged vehicles and provided maintenance and repairs.

The 758th deployed to the Mediterranean Theater of Operations in 1944 and became the only all-black armored unit to fight in Italy in World War II. This was during the Germans’ last desperate stand in Italy and the fighting was fierce. The 758th used M5 light tanks and fought the Nazis and the Fascists in northern Italy, from the beaches of the Ligurian Sea through the Po Valley and into the rugged Apennine Mountains, where they helped breach the Gothic Line — the Germans’ last major defensive line of the Italian Campaign.

Cline carried a small Leica camera with him and snapped photo after photo, some in the thick of combat. In that, too, he was rare. Very few soldiers thought to document the war from their own eyes. The photos Cline took — a destroyed tank on the side of a dirt road, soldiers going about seemingly mundane chores, buildings and towns they traveled past, an enemy shell exploding in a field — stand as a testament to the bravery of the 758th.

Cline Jr. said that his father was offered a position in another unit but refused it. “The bottom line is those men formed a relationship. They worked together, they trained together, they fought together.”

White officers assigned to segregated units during the war didn’t have it nearly as hard as minority enlisted men, who had to endure the systematic racism that pervaded the U.S. military at the time. In spite of that, the three all-black tank battalions performed valiantly, with individual soldiers racking up a slew of awards for valor including Purple Hearts, Bronze Stars, Silver Stars and a Medal of Honor. Nevertheless, it was unusual for the white officers to stick with segregated units any longer than they absolutely had to.

“For a white officer to be assigned to segregated troops was a hardship obligation. They normally served their time and immediately displaced back into the Army’s mainstream where their careers could excel,” said Joe Wilson Jr., author of the book “The 758th Tank Battalion in World War II” and son of Joe Wilson Sr., an African-American soldier who served in the 761st in World War II and later became an instructor in the 758th. “There were some exceptions like Cline. A few others come to mind, including Capt. David J. Williams II from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, who recommended Staff Sgt. Ruben Rivers for the Medal of Honor.”

[Rivers, who served in the 761st, was killed on the battlefield leading an attack on German anti-tank guns and posthumously received the Medal of Honor in 1997. Two other African-American tankers from the 761st were also nominated for the Medal of Honor – Sgt. Warren G.H. Crecy and 1st Sgt. Samuel Turley – but only Rivers received it. Of the three black tank divisions, the 761st (known as the Black Panthers) saw the most conflict and was awarded a Presidential Unit Citation for its actions. In the end, the 98 black enlisted men of the 761st earned a pile of awards for valor including 11 Silver Stars, 69 Bronze Stars and more than 300 Purple Hearts.]

Wilson Jr. estimates soldiers from the 758th earned at least 10 Bronze Stars, three Silver Stars and 20 Purple Hearts. Unlike the 761st, the 758th was broken up and cross-attached as separate companies throughout its combat tour and thus never fought as a battalion. Perhaps as a result of this, the 758th’s tour of duty was poorly documented – making the William Cline Collection all the more important.

After he returned from the war, Cline carefully placed his photos in two neatly organized albums and kept them in a place of honor in his home.

Some three decades after his passing, his son took a closer look at those albums, which he’d seen on his father’s shelves since he was a child. For the first time, he pulled one of the photographs out of its sleeve and turned it over. His father had inscribed the back with a carefully written caption that included a description, date, place and names. In minutes he knew every photo in the albums held the same revelation.

“I want this to be for my dad’s legacy. Unfortunately, he passed away in 1987 when he was only 67 years old. I lost him way too young,” said Cline Jr. “He was a quiet man. He did the right things in life; came back from the war, went to work for GE for 40 years, raised a family, did the best he could.”

But, he says, there’s a greater meaning in his father’s story that he wants to pass on to the world.

“I’m not looking for glory for my dad,” said Cline Jr. “It’s not the story of Capt. Cline — it’s the story of the 758th Tank Battalion.”

Clemson benefited from Cline’s meticulous nature and love for photography as his son presented his father’s treasures to the Clemson Library’s Special Collections and Archives on Monday, Oct. 28.

“This is full documentation of someone’s life and what they accomplished in it,” Clemson’s Dean of Libraries Christopher Cox told Cline Jr. “I think the real value comes from the detail being provided. It’s not just the history of this individual at Clemson, it’s history of the war. Someone that’s doing research here could learn about World War II, mechanical engineering in World War II, tactics, African-American history . . . there’s just so many layers that get put together with this. People will be able to do all kinds of original research and your dad will be at the center of it all.”

It is an astonishingly well-preserved body of work that’s sure to captivate World War II historians, but there is one photograph in particular that Cline’s living son would like people to explore.

“The picture that’s the most phenomenal was taken in Genoa at the end of the war,” said Cline Jr. “It’s a group photo of his unit and he is the only white soldier in it. He wrote almost every name on the back. That picture tells the whole story of my father.”

This summer he will take a dream trip to Italy to follow his father’s path through the war and get an even better sense of what the men of the 758th experienced.

In the meantime, he’s ready to pass on his father’s things to a place he trusts.

“I need somebody to take it from here,” he explained. “I want the world to know about the 758th, and that my dad was a Clemson man.”