National Puzzle Day is January 29 and celebrates all types of puzzles from jigsaws to crosswords

Whether it’s a crossword at the kitchen table before work or opening up New York Times Games before heading to that 8 a.m. lecture, many people start their day with a puzzle, often without realizing the mathematics and logical thinking that go into both creating and solving it.

Two faculty members in the Clemson University School of Mathematical and Statistical Sciences — Professor Neil Calkin and Associate Professor Eliza Gallagher — decided to make the connection more explicit by teaching puzzle classes, including their “Puzzles and Paradoxes” Honors seminar.

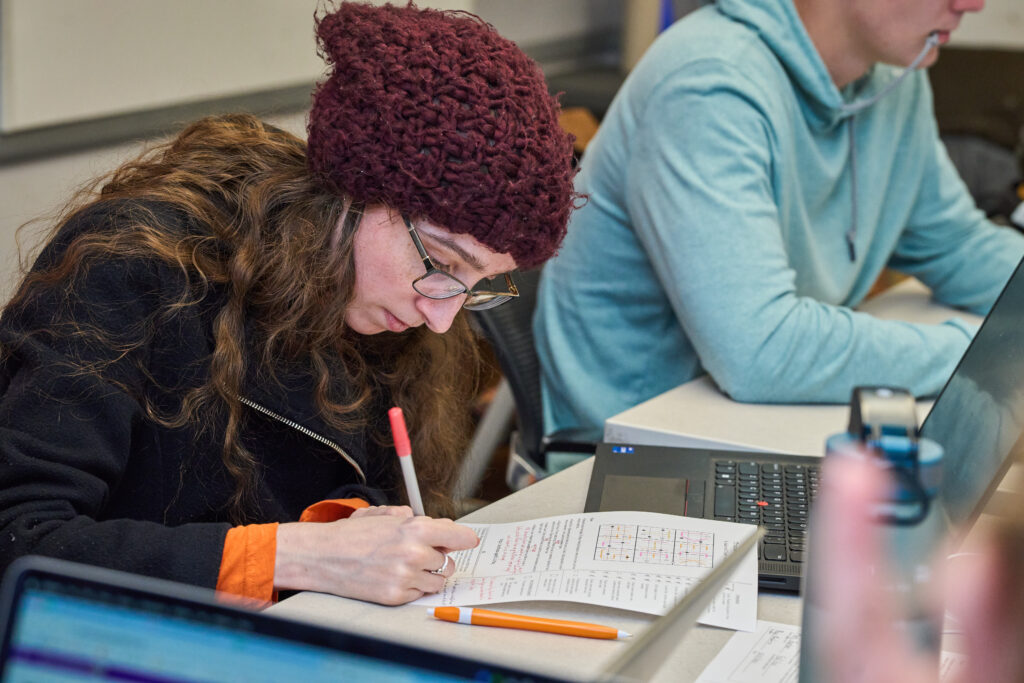

Some students in the course were intimidated by puzzles they had never tried before, while others came to see it as a welcome “brain break” from their usual classes. STEM majors in the class said it was an unexpected way to apply and develop skills essential for their major.

Hands on approach to math

Junior honors student Taylor Henry enrolled in “Puzzles and Paradoxes” after taking Calkin and Gallagher’s “Math and Magic” class.

“This has been one of my first positive steps into math,” Henry says, adding that this hands-on approach to applied math could be even more impactful if introduced earlier in students’ education.

One staple of the class is the cryptic crossword. Each morning begins with the “Minute Cryptic,” a puzzle that people around the world attempt to solve with only a single-word clue. Cryptic puzzles have different grids and clues than traditional crossword puzzles. They often rely on wordplay — including anagrams and homophones — and often include British translations and spellings. Social media videos explaining how to solve each day’s puzzle are part of the reason some students became interested in the class.

Student curiosity

“If you have carefully justified each logical step through a puzzle, what you have done is construct a proof that the solution you found is a unique solution,” Gallagher says.

The professors also hoped the class would change some opinions and attitudes about mathematics.

Misconception about math

Although puzzles usually only have one solution, there’s a level of creativity that most people don’t expect in math that students practice through solving puzzles.

Calkin and Gallagher developed the class after noticing students’ curiosity about patterns in sudoku puzzles and whether those patterns always hold. They emphasized mathematical reasoning, asking students to justify each step of a solution, whether that meant explaining a cryptic crossword clue or walking through solving a sudoku puzzle.

“There is a misconception about mathematics that there is one way to solve this problem. In reality, there are multiple paths to get to an answer,” Calkin says.

Calkin and Gallagher wanted the course to go beyond solving different types of puzzles, however. By also teaching students how to create the puzzles, the pair aimed to build confidence, encourage creativity and help students find joy in puzzles.

Up to the challenge

Creating puzzles initially made some students nervous, but the class gradually worked through the process together before transitioning to creating their own cryptic crosswords and sudokus.

Calkin and Gallagher later compiled student-created puzzles into three volumes of books, with class alumni still submitting work they created years later.

Many of the students have since joined the international puzzle-solving community, signing up together for time slots in a 24-hour livestream puzzle-solving event.

“There’s a benefit to solving puzzles with other people because most puzzles have more than one way to reach the solution, and every person’s brain works differently,” Calkin says.

The livestream is through a group that Calkin and Gallagher participate in called Sudoku Con, to help promote an international conference on sudoku. Last year, the conference was held in Boston. Calkin and Gallagher brought three students from the class with them to participate.

Calkin and Gallagher plan to select student-created puzzles to send to BremSter, a YouTuber with approximately 6,000 subscribers who regularly solves puzzles online.

“If BremSter features a puzzle, it can get a thousand solves. When you think about a puzzle taking 10 to 20 minutes for an ordinary person to solve, even 100 solves adds up to about 300 hours of joy,” Calkin says.

Gallagher and Calkin have created a website where they have posted a new set of variant puzzles every day for the past two years.