If you ask longtime educator, three-time superintendent and Pickens County Board of Education trustee Betty Bagley how her career in public schools began, she’ll tell you: “By accident and good fortune.”

The “accident” has something to do with growing up as an ambitious young woman in the 1950s and saying “yes” to every opportunity that came her way. The “good fortune?” That came from the people she surrounded herself with as a high achiever who cares deeply about children.

A member of the Class of 2023’s educational leadership cohort, Bagley spent 10 years working toward her Ph.D. from Clemson’s College of Education. Her pursuit of knowledge, however, began seven decades earlier.

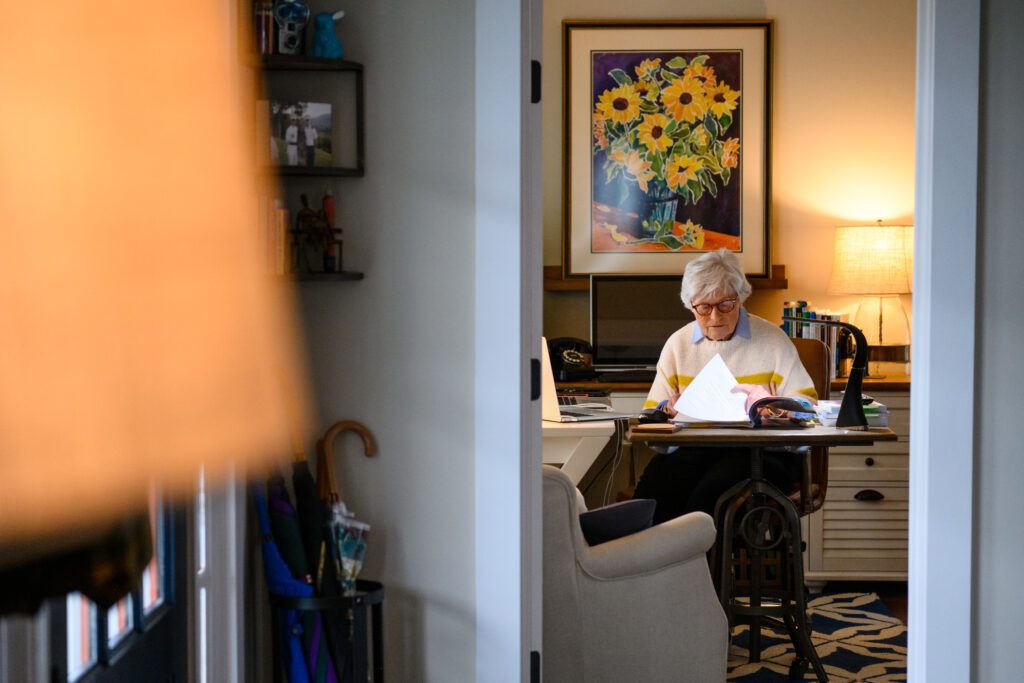

“I look in the mirror, and I’m shocked,” Bagley shared recently from her Clemson home office, cap, gown and hood hanging from a bookshelf brimming with moments from a storied career.

That’s because even though many decades have passed since her earliest school days, if you ask her, she still views the world with the eyes of a schoolgirl. Bagley was a pupil at Norris Elementary School, attending class in a two-story brick building just a few miles from the University’s campus. When she started grade school, Clemson was still an all-male military academy.

Pigtails in her hair and wearing a plaid shirt, corduroy pants and Buster Brown shoes, one of her earliest memories was of the principal ringing the bell on the school’s front steps, loudly.

That simple sound filled her mind with possibilities.

Eventually those possibilities became a passion. Now, Ph.D. in hand, she’s setting about the work of helping others see what she sees, in hopes they will set their minds toward making a difference in the lives of South Carolina’s children.

“She believes in herself and everyone around her,” says Karla Kelley, current Pickens County School Board chair. “Nothing is too hard for Betty Bagley. She consistently pursues innovation for our student population, and she is always looking for ways to make the world around her better. She is a superhero without a cape.”

A student and a teacher

An educational leadership Ph.D. is not the first advanced degree Bagley has earned — or even the second. It’s not even her first Clemson degree.

But her most recent diploma is significant because it encapsulates every class she’s taken and every experience she’s had throughout a storied 50-year career in public education.

South Carolina has nearly 80 school districts that employ more than 51,000 educational professionals. However, there is no single mechanism for connecting one superintendent to another to share professional experiences. So, for her dissertation, Bagley inquired of South Carolina superintendents: “Who is this person who chose the profession of education and rose to its highest leadership level, assuming both school communities’ trust and burdens of accountability?”

For three state school districts, the answer to that question was simply, “Betty.”

The decade she spent pursuing her Clemson degree meant reliving those school district appointments, one by one. “There was,” she says, “a lot of life in between those years.”

The focus of her dissertation answered the autobiographical question: “What does my journey, what do my experiences, reveal about educational changes in the last 30 years that influenced the office of a public-school superintendent?”

The data sources for Bagley’s dissertation included 827 artifacts — professional documents, archival notes, and perspectives from colleagues and state officials — all drawn from her own professional life as a career educator and school superintendent. The answer to helping others succeed, she found, was this simple message: “Share your story.”

From small beginnings to school leader

Local school superintendents carry responsibilities for instruction, school operations and accountability; yet the communities that superintendents serve often do not know them well, if at all. Bagley explains this from her tidy home, just a few miles from campus in Clemson’s Patrick Square community.

Her home, which she graciously opens to friends and family, is an extension of her life. Music is always playing in the background. Each room is always perfectly decorated for the season (including more than 30 decorated trees last Christmas), and as one moves from room to room, it feels like a cross between a small-scale Biltmore and a Gilmore Girls movie set. Glimpses of her life and family are everywhere.

She refers to her home as her “project,” and it is dedicated to the family she loves,

And Bagley’s dissertation was dedicated to “past and present superintendents who can fill the gap in our literature about the day-to-day operations of the school superintendent.” She urges them to share their stories and contribute to a needed body of work that can aid in developing future superintendents.

This void will continue to deepen if we as superintendents do not lead the way.

Betty Bagley, Class of 2023, Ph.D., Educational Leadership

Over the course of her career serving public schools, Bagley has seen it all. Leading from a place of experience means sharing those experiences with the people who will follow in your footsteps, she says.

When she got to college, she had the support of her family, but professionally, expectations for her achievement weren’t that high. In the 1950s and 1960s, girls could be teachers, nurses or secretaries, so she focused her work on human behavior, interactions and relationships. But she also focused on friends and having fun.

She cheered; she competed; she celebrated. And, she says, she found her way a little later than others, something that guides her learning philosophy even today.

“My message to kids is, ‘Who said we had to be ready for school at age 6? Who said we had to graduate at 18?’ It takes some people longer to mature,” and she counts herself as one of those, even offering that she has a processing difference that still requires her to make special notations when delivering a public speech.

By her sophomore year at Central Wesleyan College, now Southern Wesleyan University, Bagley began to see clearer glimpses of her future. She was still working on her B.A. in psychology with minors in education, Bible and social studies when her first job offer came from the principal of Pendleton High School in Anderson County.

Before she’d graduated or even earned a teaching certificate, he offered her a contract to teach psychology, mathematics and physical education and coach the varsity girls basketball team.

Bagley accepted. “I taught these classes with a major in psychology, without the benefit of student teaching and absent a teaching certificate,” she recalls, “but I soon remedied the latter.”

Within the year, she secured a permanent teaching certificate and enrolled at Clemson University to pursue an M.Ed. in school counseling. She also added special education certifications to her initial teaching certificate and finally added an advanced school counselor certificate upon completion of her M.Ed.

It was the beginning, but far from the end, of a habit of saying “yes” to every educational opportunity that came her way.

She married, and her husband Sack’s career then moved them to Bamberg, a rural county in South Carolina’s coastal plains. It was the middle of the school year, so she secured the only teaching position available to her in a kindergarten classroom. In short order, she was appointed director of student services, and she enrolled in South Carolina State University to begin earning her certificate in administration.

The more Bagley learned, the more her professional responsibilities grew, and the more she realized she wanted and needed to learn more.

“She’s never quit. Not once,” says her daughter Tyler Vereen, a pediatrician in North Carolina. One of her most indelible memories from childhood was sitting at her kitchen table and taking the “new tests” her mother would bring home designed to measure proficiency.

She is always practicing and gathering and reaching for knowledge. She wants to know everything she can, so she’s always learning more.

Tyler Vereen, daughter of Betty Bagley

Soon Bagley enrolled at The Citadel to pursue an administrative certificate and an Education Specialist (Ed.S.) degree. She re-enrolled at The Citadel and pursued an Ed.S. degree in school psychology. In addition to being director of special services for Bamberg District 1, she became the school psychologist for the district. That led to coursework at the University of South Carolina, where she took 30-plus hours in courses such as reading, curriculum management, attention deficit disorders and autism.

Bagley pursued her love of school and learning all the way into the Bamberg District 1 superintendent’s office. More than 15 years passed between when she arrived in the county and when the superintendent’s position became open. It was 1993.

“I submitted my resume and application to the district office within the last hour of the due date for applications,” Bagley recalls. “I did so in hopes of conveying to the board the need to move progressively into a 20th-century education model.

“I saw the community and its teachers, administrators and students as ready to embrace new ideas, strategies and initiatives.”

Her school district must have liked what it saw because Bagley got the job. However, she kept all her existing jobs, too. She maintained her roles as a school psychologist, professional development coordinator, curriculum coordinator, maintenance coordinator and technology coordinator for the district.

“For seven years, a fire burned in me that has been unmatched,” Bagley says of those frenetic days in the Bamberg superintendent’s office. “I experienced these years as a wealth of opportunity and growth for the district and me.”

Under her guidance, a district mission and vision that captured the essence of how the school and community traveled together were developed. It was a blueprint for district purpose and guidance, one that showed, Bagley explains, “our collective understanding of our direction.”

Advocacy close to home

That same year that she stepped into the superintendent’s office for the first time, Bagley said “yes” to yet another new role: advocate. In 1993, Bamberg District 1 signed on to the Abbeville County School District v. State of South Carolina lawsuit. The families and districts involved in the case accused the state of inequitable funding for schools in their part of the state.

Her daughter, Ty, was then 12 years old and in the seventh grade, and Bagley knew firsthand there were inequities between the Bamberg schools and the ones she grew up attending in the Upstate. Her daughter’s classes were minimally or even less than minimally adequate, held either in portables that were twice her age or in buildings constructed in the mid-1940s.

“On behalf of my daughter, I joined the lawsuit for equity and justice,” Bagley recalls in her dissertation. “As superintendent and as a mother, I felt morally compelled to stand for the district and my family in this lawsuit.”

In Bamberg, in particular, she says, “We could have been the mascot for zip code deprivation.”

To sustain their schools, parents, teachers and administrators sold trees to buy paint for 25-year-old portables and new roofs. She bought “the back end of a refrigerator truck” for $200 to make a room for speech classes.

“We sold thousands of donuts to buy basic equipment and materials,” Bagley recalls. “At one time, another school district adopted us and gave us desks, tables, chairs, filing cabinets and other equipment. The community came together on behalf of the students.”

The landmark lawsuit to improve access to and funding for public education for rural school districts would stretch on for more than 20 years and resolve unceremoniously in Bagley’s view. But there were more challenges to tackle, and so she carried on even as the lawsuit crawled forward.

“There is nobody I know who has more passion, more relentless drive, more enthusiasm and genuine care for kids than my mom.

Tyler Vereen, daughter of Betty Bagley

“She is perfect. She is my favorite,” Vereen says. “She’s so caring and always in your corner. It doesn’t matter who you are, what town you live in, how much money you have, what you do. She is in your corner.”

School choice and magnet programs

In 2000, the Anderson School District 5 board selected Bagley to become their superintendent, and she brought her passion for students and her urgency for change by way of unique magnet schools, which still remain in District 5 today as a model for specialized programs across the state.

An art school, a school of technology and a charter school are just a few of the innovative options Bagley helped grow for the district. A curriculum was developed from her work that became a model curriculum for the State of South Carolina. She won South Carolina Superintendent of the Year. It was 2008.

Not long after, Bagley reinvented herself yet again by transitioning out of the superintendent’s role and into a position traveling the state as an educational consultant. She used her experience and knowledge to observe and elevate the best practices of South Carolina’s public school teachers. Her role included promoting personalized learning and developing the profile of the South Carolina graduate adopted by the state department of education.

By this time, Betty was four years into her Ph.D. program at Clemson and sometimes putting hundreds of miles on her car each week as a consultant for the state education department. In 2016, a new challenge presented itself: running for office. She won a seat on the Pickens County Board of Education, eventually becoming chairwoman of the board. She continues to serve as the District 1 schools trustee, representing Clemson-area families.

“There is never a dumb question with Betty. She is always willing to teach, listen and entertain additional viewpoints,” says her colleague Karla Kelley from the school board.

“I can think of nights when we spent hours on the phone talking about how to make things better while the rest of the world is asleep,” Kelley says. “And every discussion always ends with a smile.”

Then, in 2018, while still going to Clemson, serving on the school board and being a wife and mother, she found herself back in the superintendent’s chair — on an interim basis for McCormick County.

The children needed her, so there was only one answer: “Yes.”

Celebrating a milestone

Nothing will ever replicate the fire and enthusiasm she experienced during her first superintendent’s appointment, Bagley says. She served in McCormick until a replacement could be found while also finishing up her degree.

“Everything I’ve done, I’ve felt like it was preparing me for something else,” she says.

In April 2023, she successfully defended her dissertation and then celebrated by traveling to Europe with daughter, Tyler who, Bagley says, “would not give me permission to give up.” The trip was Ty’s graduation gift to Bagley. But the true gift, says Bagley, was the steadfast love and support her daughter gave her throughout the journey.

“She has been my rock because there have been moments when I asked, ‘Why am I doing this?’”

Many of those difficult moments came while caring for her husband and love of her life, Sack Bagley. An avid Clemson sports fan and former Pendleton High School football coach, Sack was diagnosed in 2012 with a form of progressive dementia and Parkinson’s disease that slowly took him from her. Her “biggest cheerleader,” Sack died in August of 2022. They were married 52 years.

When it came time for Bagley to present her dissertation defense, Bagley’s son, Chad, his wife, Susan, along with daughter Ty and her husband, Will, were all present via Zoom; her three grandchildren were rooting her on from across the country. And Sack was there in spirit.

“I had my family with me,” Bagley says.

She spoke to the need for superintendents’ firsthand perspectives alongside curriculum leadership frameworks for practicing and aspiring superintendents and a call for practicing superintendents to use their position and voice in advocacy and accountability for their students and communities.

Her story will inspire generations of educators and public school leaders to learn from one another, to educate to and advocate for students, to navigate public policy with more transparency, and to support one another in their efforts.

“My story may generate more stories from superintendents’ reflections on their roles in educational policies and change among the towns, regions and states where they lived and worked,” she says.

Remembering the beginning

Bagley’s passion for public education was ignited in a two-story brick schoolhouse located in the shadow of an all-male institution from which she would one day graduate. Twice.

Her principal rang the school bell each morning to start the day. Until one morning, he allowed a student to assume the job.

Life as Bagley knew it was changed.

The feeling of her hand as the mallet struck metal.

The pigtails in her hair.

The worn leather shoes on her feet. The memory of it is as clear in her mind as if it happened yesterday.

“It made a huge impression on me,” Bagley says. “I said then, I’m not letting this go. And I haven’t. Every August, I’m still ringing that bell.”

Get in touch and we will connect you with the author or another expert.

Or email us at news@clemson.edu