Clemson animal health experts are educating South Carolina livestock producers, veterinarians, meat processors and pet owners about the New World screwworm (NWS), a parasitic blowfly whose larvae feed on the living tissue of warm-blooded animals and could threaten the state’s agriculture industry.

Although no animal cases have been reported in the United States, the Mexico National Service of Agro-Alimentary Health, Safety, and Quality (SENASICA) on Sunday confirmed a new case of NWS in Sabinas Hidalgo, Nuevo Leon, less than 70 miles (113 km) from the U.S.-Mexico border, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) said.

“USDA is analyzing all new information related to the recent case in Nuevo Leon and will pursue all options to release sterile flies in this region as necessary,” USDA said.

The risk to humans is considered low, but public health officials urge caution. On August 4, a Maryland resident who had traveled to El Salvador was diagnosed with an NWS infestation, the first confirmed human case in the United States in years. The patient has since recovered, and no further spread has been identified.

South Carolina State Veterinarian Michael Neault, director of Clemson Livestock-Poultry Health, said his agency is working with state and federal officials to monitor NWS, create trapping protocols and educate the public.

“We are working with the U.S. Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service and animal health agencies in other states to monitor the movement of NWS and prevent its spread should it enter the U.S.,” Neault said. “But we can’t be everywhere at once, so that’s why we are educating the public and asking them to report any suspicious findings. Also, it’s important for the public to understand that NWS is treatable and animals can make a full recovery if it is detected early.”

Signs and Symptoms of New World Screwworm

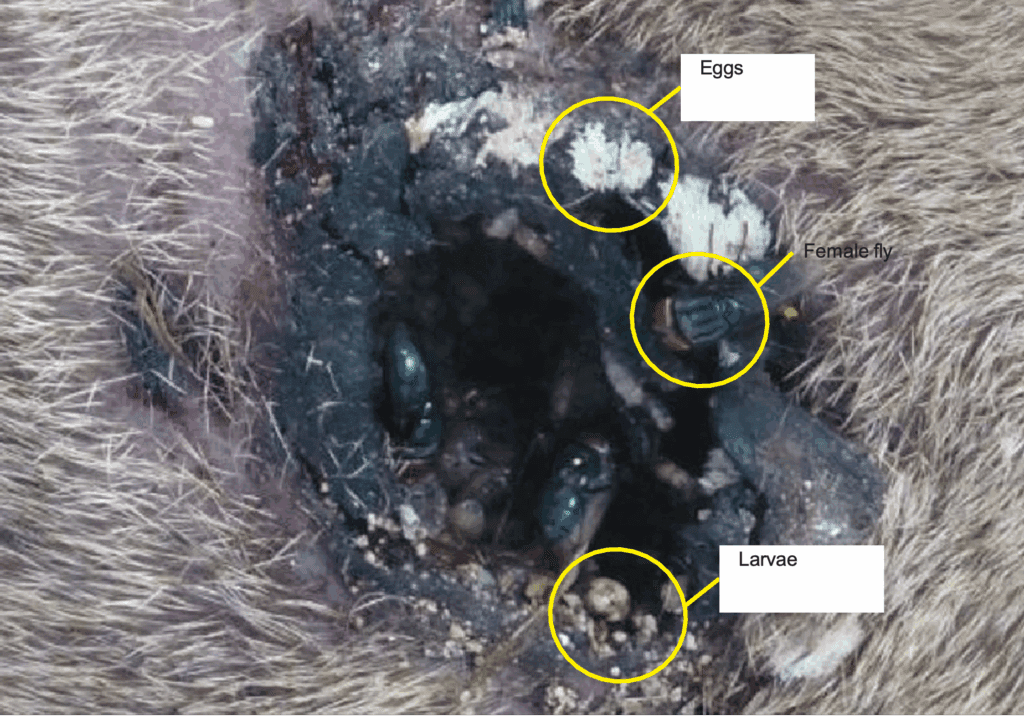

- Visible maggots in or around wounds, nostrils, eyes, ears, mouth or umbilical cords of newborn animals

- Foul-smelling discharge from wounds due to tissue destruction

- Rapidly enlarging wounds that do not heal normally and may deepen with time

- Restlessness or irritation in affected animals, including rubbing or scratching at wounds

- Loss of appetite or reduced weight gain in livestock due to pain and infection

- Lethargy and weakness as infestations progress

- Secondary infections around the wound site, often with swelling and redness

- Behavioral changes, such as isolation from the herd or reduced mobility

- In severe cases, death from untreated infestations

Report Suspicious Cases Immediately

Suspected cases of NWS should be reported to:

- If you suspect a case in a person: Report immediately to South Carolina Department of Public Health via the regional epidemiology office or the statewide emergency number (1-888-847-0902).

- If case is in deer and wildlife: S.C. Department of Natural Resources, Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries Division, (803) 734-3886

- If suspected in domestic animals: Clemson University Livestock-Poultry Health, (803) 788-2260

Steps to Prevent Infestation

While no NWS cases have been reported in South Carolina, vigilance is essential if outbreaks escalate in nearby regions. Livestock and pet owners are urged to:

- Monitor animals for suspicious wounds, visible maggots or behavioral changes, and report concerns immediately.

- Clean and cover wounds promptly and use appropriate repellents on animals and people, especially outdoors.

- Recognize that human cases are rare, but those with open wounds or frequent animal contact should exercise caution.

- Stay informed about ongoing federal prevention efforts, including sterile-insect releases, border surveillance and emergency treatment protocols.

Movement of Animals is Strictly Regulated

- Certificates of Veterinary Inspection (CVIs): Federal regulations require accredited veterinarians to issue CVIs for interstate animal transport, enforcing quarantine, sanitation and animal identification protocols.

- Prohibition on Transport of Diseased Animals: Animals infected with exotic diseases, such as NWS, cannot be moved interstate under federal law.

- Suspension of Imports from Mexico: In response to NWS detection in southern Mexico in 2024, USDA suspended imports of live cattle, horses and bison.

Federal Efforts to Prevent Outbreaks

The United States relies on the Sterile Insect Technique (SIT) to prevent NWS spread. In this program, millions of male screwworm flies are reared in specialized facilities, sterilized with radiation and released into the environment. When sterile males mate with wild females, no offspring result, reducing the population and breaking the cycle of infestation. USDA and its partners maintain ongoing sterile-fly releases along the southern border, creating a protective barrier against reintroduction. This program is recognized as one of the most effective and environmentally safe pest control strategies in modern agriculture.

History of the Last Outbreak

The screwworm was once widespread across the southern U.S., causing severe losses in livestock. After SIT was introduced, the pest was declared eradicated from the country in 1966, with programs extended southward through Mexico and Central America.

The most recent U.S. outbreak occurred in 2016 in the Florida Keys, affecting endangered Key deer and domestic animals. Hundreds of deer died before state and federal agencies launched an emergency SIT program, releasing 150 million sterile flies over several months. By March 2017, the outbreak was declared eradicated. Since then, continuous surveillance and sterile fly releases along the Panama–Colombia border have served as a protective barrier until NWS broke through the protective barrier and moved over 1,600 miles from southern Panama to southern Mexico in about two years.