Children gathered at the Greer Center for the Arts to paint ceramic butterflies and honor one of their city’s native sons on April 18. The late Horace Berry ’41 probably could never have imagined such an event happening in his honor a century after growing up in the close-knit mill town, but heroes often come from humble beginnings.

Berry was the son of a rural postal carrier — initially by horse and buggy and later by motorcycle — who owned several hundred acres of land north of Greer that was home to the Berry mills, a family operation powered by two large waterwheels that ground corn, wheat, and sawmill and operated a cotton gin. Berry grew up on Main Street, but the family land also had a fishing pond, so the young man spent school days in town and much of his free time helping the family with the fishing pond and mills. After high school, there was only one place he wanted to go and that was Clemson University, just 50 miles to the west.

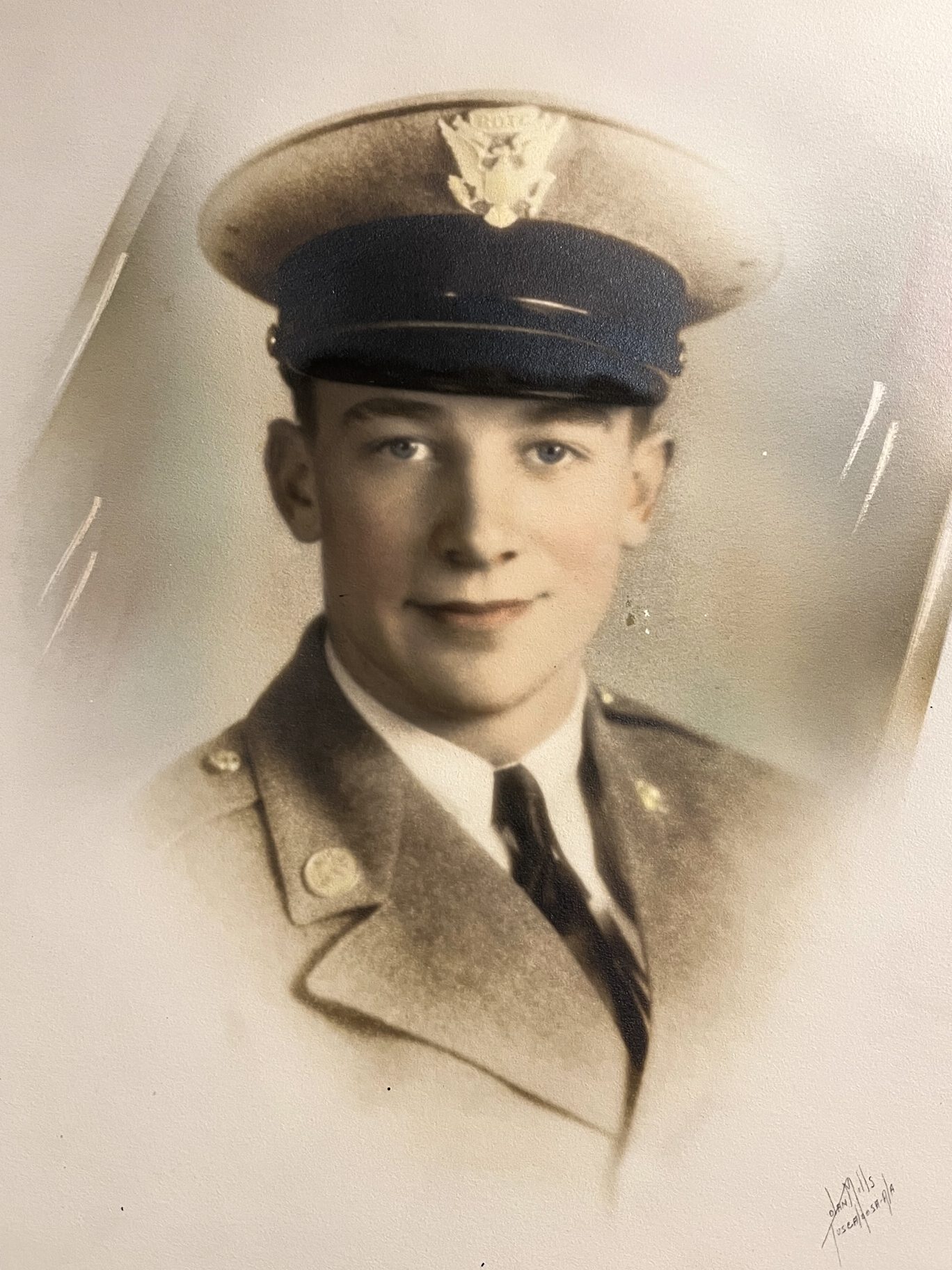

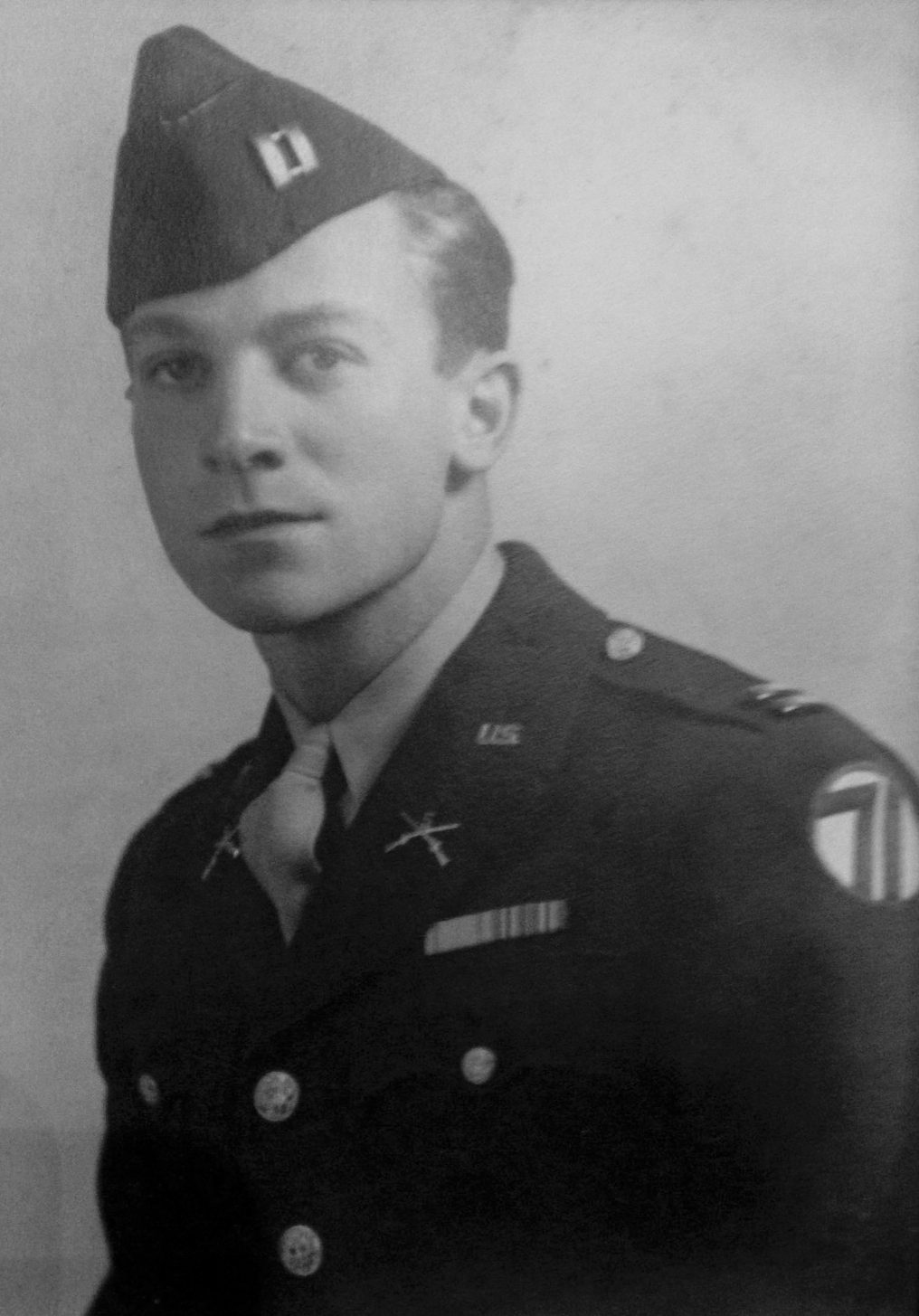

After graduating from Clemson with a degree in entomology, Berry was commissioned into the U.S. Army and went directly to active duty. He served at various bases in the U.S. for the first two years and then at the Panama Canal for a year before finally being deployed to Europe with the 71st Infantry Division in January 1945 as WWII was rumbling to an end. His company faced sporadic fighting as the Germans retreated, and he earned a Bronze Star for valor during one such engagement where he exposed himself to enemy artillery fire to call in coordinates.

To help honor Berry and his role as a liberator, the city of Greer is participating in The Butterfly Project, a campaign started in California in 2006 to create and display 1.5 million unique butterflies worldwide, one for each child who died in the Holocaust. The city of Greer is partnering with the Greenville Jewish Federation to take part in the project. So far, the city has collected 550 colorful tributes.

His story and the accounts of his fellow soldiers have been well-documented: On May 4, 1945, just three days before Germany surrendered, Berry and his unit were sent into the woods outside Lambach, Austria, to inspect the Gunskirchen concentration camp. As they approached the camp, they found themselves moving against a stream of hundreds of people so thin they looked like walking skeletons, fleeing the opposite direction — away from the place. Emaciated bodies were scattered along both sides of the muddy road. It was the most horrible sight they had seen in the war — but even then, in their worst nightmares, Berry and his men could not have imagined the scene they found once they arrived at the camp: thousands of sick and starving people — some so emotional at seeing American soldiers they sobbed uncontrollably, some so weak they couldn’t lift their heads — and death everywhere.

Berry’s unit was swarmed by the starving prisoners and set about the daunting task of helping — first giving away all the rations and water they had and then arranging for food and water deliveries from nearby towns and Nazi-owned warehouses. Despite the mass exodus in the days before, it is estimated there were some 15,000 prisoners still there when the 71st entered the camp.

One of Berry’s comrades, Cpt. J.D. Pletcher, described the scene in a written account used in a pamphlet produced by the U.S. Army:

“It is not an exaggeration to say that almost every inmate was insane with hunger. Just the sight of an American brought cheers, groans and shrieks. People crowded around to touch an American, to touch the jeep, to kiss our arms — perhaps just to make sure that it was true. The people who couldn’t walk crawled out toward our jeep. Those who couldn’t even crawl propped themselves up on an elbow, and somehow, through all their pain and suffering, revealed through their eyes the gratitude, the joy they felt at the arrival of Americans.”

The American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise (AICE) describes what Berry and his men experienced in the weeks that followed this way in the Jewish Virtual Library:

“It was V-E Day. While the world celebrated, the weary men of Company ‘K,’ 5th Regiment, 71st Infantry Division, commanded by Capt. Horace S. Berry of Spartansburg (sic), S.C., faced the task of cleaning up Gunskirchen Lager, a German concentration camp near Lambach, Austria; of sending the living to hospitals, of supervising the burying of the dead, of trying to cover the stench coming from the half-finished buildings in the woods. They had been working at the job since May 5, the day after Company ‘M’ and Company ‘K,’ like all others who saw it, will never forget.”

On May 8, 1945, World War II in Europe came to an end. Even after the liberation, some 1,500 former prisoners died due to their mistreatment in Gunskirchen. The camp had only been operational since March 1945, but in less than three months, between 2,700 and 5,000 prisoners were murdered there. If Berry and his fellow brothers-in-arms hadn’t arrived when they did, there is no telling how high those numbers would be.

After the war, Berry returned to South Carolina and used his Clemson degree to forge a successful career in the peach and apple crop business, working with the South Carolina Peach Growers Association, Clemson Extension and the Ortho Division of Chevron. He never spoke of what he’d experienced in Austria. Even his children didn’t know what he’d seen until Berry did an interview with the South Carolina Council on the Holocaust in the early 1990s.

“He was a humble man that accomplished many things but did not want or care for the limelight,” said Berry’s son, Carl. “He and other concentration camp liberators witnessed firsthand the atrocities of the Nazi regime. They would want the story to continue to be told.”

Berry passed away just a year after he gave that interview.

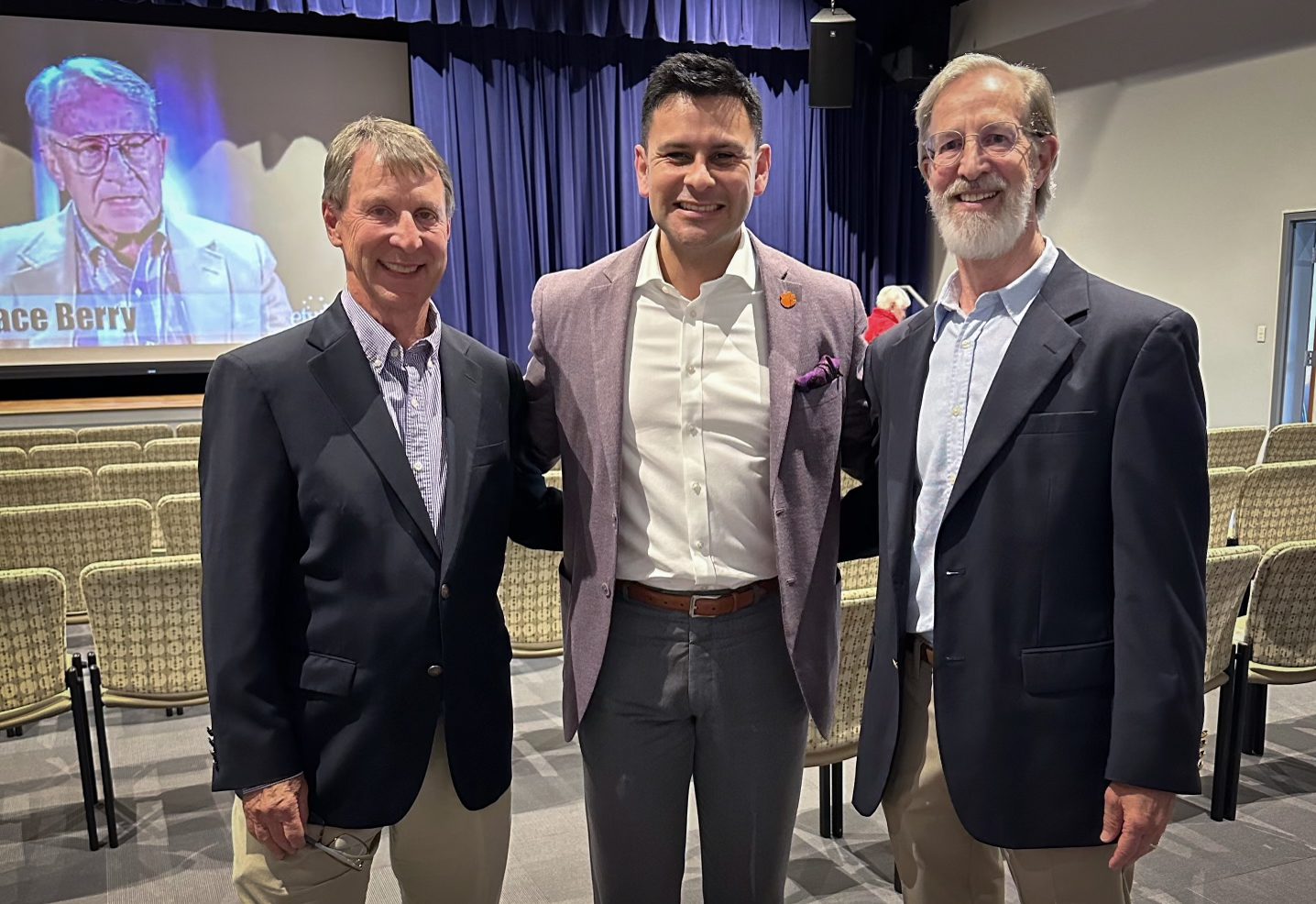

Three generations of Berry’s family attended the event on April 18. In addition to Berry, his brother-in-law James Gallman ’54, son Carl Berry ’76, daughter-in-law Susan Lee Berry ’76, and grandson Christopher Berry’10 are all Clemson graduates.

“The Berry family is truly honored that our father, Horace S. Berry, has been recognized and remembered by his hometown of Greer as a concentration camp liberator,” said Carl.

Julio Hernandez, assistant to the president for community outreach and engagement, attended the event on behalf of the Clemson Family.

“Horace Berry exemplified our Clemson values, and reflecting on his life of courage and service is inspiring,” said Hernandez. “We are thankful for the sacrifices Mr. Berry and his family have made to make a difference across our state, country and the world.”

“It is very much appreciated that Julio attended the ceremony in Greer,” said Carl. “It shows that we are one Clemson Family.”

Berry’s other son, Ladson, echoed his brother’s sentiment.

“Our family is very honored to have Clemson recognize him,” said Ladson. “Dad spoke fondly of his time at Clemson. He and our mom, Sara Foster Berry, attended many alumni events and were huge supporters of Clemson Football. They purchased season tickets starting in the early 1950s, and my brother’s family and my family still sit in those same seats. Our family has been attending Clemson Football games for 70 years!”

The butterflies created by the citizens of Greer will become an art installation that will be placed in Berry’s honor in the butterfly garden outside the Greer Center for the Arts later this year.