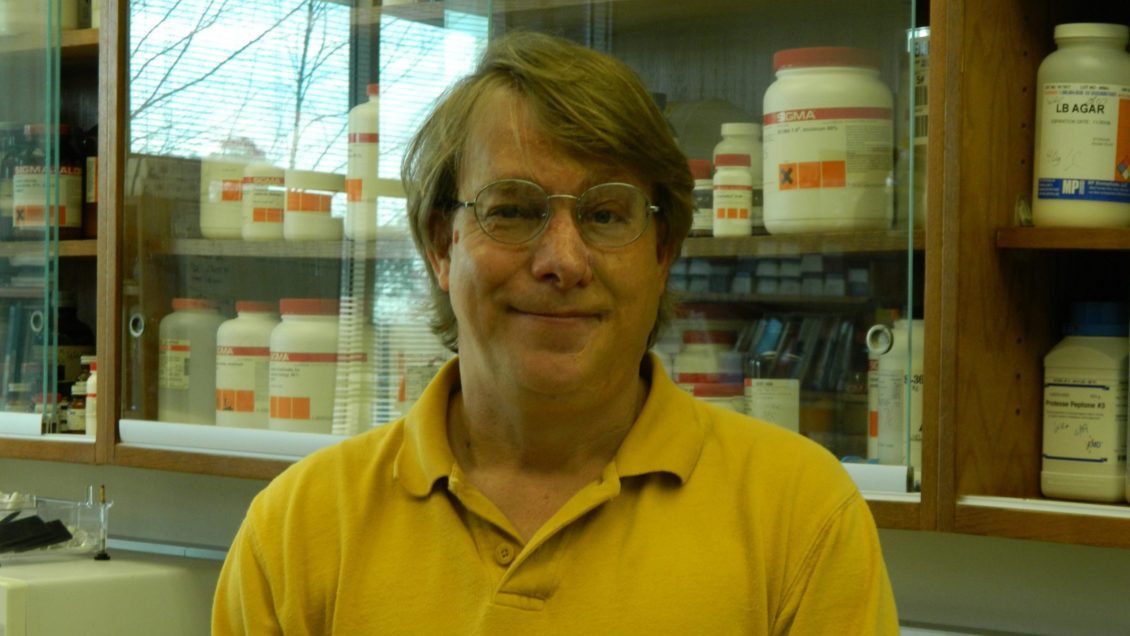

When Patrick Wechter was hired as the new Director of Clemson University’s Coastal Research and Education Center (CREC), moving into his new office didn’t require much logistical expertise.

“Literally, if I’d cut a hole in the floor of my previous office, I could’ve just dropped into my new office,” Wechter joked. “I should’ve just done that. It would’ve been easier than hauling all my stuff downstairs.”

But for a research plant pathologist such as Wechter, who spent the previous 17 years with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) at the U.S. Vegetable Laboratory (USVL) in Charleston, S.C., there’s nowhere else on earth he’d rather be.

“Charleston is unique, and it’s not just unique for South Carolina, but it’s really important for both U.S. and world agriculture: Charleston is by every measure the proving ground for plant disease and plant resistance,” he said. “If there is a plant pathogen — whether it’s bacterial, viral or fungal — it would be at home in Charleston. It’s hot and it’s humid a good part of the year, and pathogens love that. I’ve always told people, ‘If a breeding line we develop can survive in Charleston, it will survive anywhere.’ And sure enough, the lines that we have released have done just that.”

The CREC conducts applied research, education and public service programs on vegetable and specialty crops. The center includes 325 acres in addition to laboratories in the USVL building. So Wechter has already been successfully collaborating there with Clemson faculty and students for many years.

And Wechter admits the move is a bit like “coming home again,” as he earned both his Master’s degree and Ph.D. in Plant Pathology from Clemson after getting his bachelor’s degree from Winthrop University.

“I kind of got a start down here a long time ago while working on my graduate degrees,” he said. “I’m able to work with all the same people I was working with before. I tell people: Clemson and USDA are basically the same people; you can’t tell them apart. We have many of the same goals and work together to solve agricultural issues, and the two entities have been one big, happy family for a while.”

“It’s been a simple transition — nothing has really changed except the color,” he added. “I’ve gone from green for USDA to orange for Clemson.”

Over his career, Wechter has worked with a variety of pathogens and vegetable crops and has developed important cultivars with significant impact on the vegetable industry.

Wechter was selected for the position after a national search, and his career accomplishments made him the top choice to lead research efforts at Coastal REC, according to Paula Agudelo, Director of the Clemson Experiment Station.

“He developed the mustard green cultivar ‘Carolina Broadleaf’, the only commercially available brassica leafy green with resistance to Bacterial Leaf Blight, an important disease in the southern U.S.,” Agudelo said. “He also developed, in collaboration with Clemson scientists, the watermelon grafting rootstock ‘Carolina Strongback,’ which has high levels of tolerance to Fusarium wilt and resistance to root knot nematode. Carolina Strongback has been licensed to Syngenta Seed and has been made available in many countries around the world.”

Clemson’s six Research and Education Centers, collectively known as the Clemson Experiment Station, are strategically located throughout South Carolina and are an interconnected network of labs and collaborative scientists and students tackling challenges in the areas of precision agriculture, plant genetics, natural resources management, sustainability, soil health, agribusiness management, livestock production and more.

The CREC, in particular, conducts research to improve production technology for the vegetable industry. In cooperation with the Clemson University Extension Service, local problem-solving and grower educational programs receive major emphasis.

“This is a very rare unit where the University is embedded with the USDA; it’s usually the opposite of that. But this has been a working model for quite some time,” Wechter said.

Wechter has performed as Acting Research Leader for the U.S. Vegetable Laboratory on several occasions. He has also served in different capacities in the American Society of Microbiology, the American Society of Horticultural Science, and the American Phytopathological Society, including service as Senior Editor for bacteriology for the journal Plant Disease. He is the recipient of the prestigious T.W. Edminster Research Associate Award by USDA (2014) and has over 70 peer-reviewed publications.

“For me, my happiness is in my research. I haven’t been able to spend as much time on my research over the last few weeks, but that will all come back,” Wechter said. “I don’t plan to be an administrator who sits in his office all day. I’m still on a lot of graduate committees, so I spend a lot of time with my students. I spend a lot of time with the other Clemson faculty, as well as the USDA scientists. I was always very close to all the students and all the faculty before I made this move.”

And for Wechter, the name of the game in agriculture these days is “host plant resistance,” trying to move disease resistance into a crop that South Carolina growers and producers can utilize while maximizing both sustainability and profitability.

“What I’m passionate about is figuring out ways to use host resistance — basically, finding resistance in plants that we can move into something you can actually eat,” he said. “To me, it’s always been about vegetables. If you can’t eat it, I’m really not interested in it.”

Wechter said a major part of what his research team does is to develop molecular markers that allow them to track the resistance in our breeding programs.

“This allows us to shorten, or even skip a lot of steps, and push that resistance into the crops much faster, and that’s kind of the key now in agriculture,” he said. “Because new pathogens can move into our state fast; we have to be able to identify the pathogen, identify sources of resistance and incorporate that resistance into cultivars that would be acceptable to our growers and processors.”

“Clemson and USDA are uniquely situated to perform all this work very quickly. If we’re going to stay on top of the growers needs in South Carolina and making sure that they can keep growing, this is the only way to do it. Because they can’t wait 10 years for a new, resistant cultivar to be put in the field,” he added.

Get in touch and we will connect you with the author or another expert.

Or email us at news@clemson.edu