Recent Clemson University Ph.D. graduate Rhett Rautsaw wanted to explore whether the evolutionary theory of character displacement — when two species live in the same area and evolve to avoid competing over resources such as food — extended to pit viper venom.

There was one problem. To study competition, Rautsaw had to know where each pit viper species lived, and there wasn’t a comprehensive source of that information readily available.

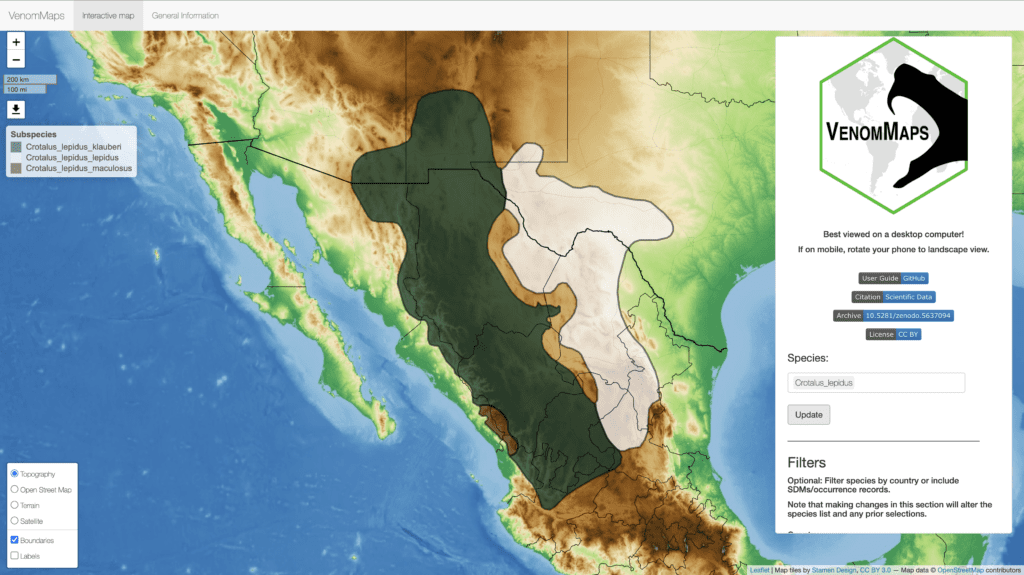

Rautsaw created VenomMaps, a database and web application containing updated distribution maps and niche models for all 158 pit viper species living in North, Central and South America. Pit vipers are a group of venomous snakes, including rattlesnakes, copperheads and cottonmouths. While Rautsaw needed the information for his evolutionary biology research, the maps provide vital information for conservation efforts, citizen scientists and medical professionals.

Venomous snakes are found on every continent except Antarctica. Most medically significant species — those resulting in hospitalization, permanent injury or death to humans — fall into one of two families: vipers and elapids (cobras, mambas and their relatives). Venomous snakebites cause nearly 100,000 deaths and 400,000 disablements globally every year.

“Pit vipers are responsible for more than 98 percent of snake bites in North, Central and South America,” Rautsaw said. “Having accurate species distributions is critical because snake venom can vary tremendously between and within a single species.”

For instance, some pit vipers have venom with 10 individual toxins while others’ venom has 100.

Mapping where they live

“With these distributions, researchers can better assess an area’s vulnerability to snakebite. By knowing which species live in their area, medical professionals will be able to treat envenomated patients better,” Rautsaw added.

Rautsaw and his collaborators constructed the app’s user-friendly, publicly accessible maps using global occurrence records from several databases, published distribution maps, field guides, U.S. Geological Survey maps, recent scientific publications and species distribution modeling.

The app uses scientific names — not common names — and shows ranges by country. The map shows the area where each species lives, but that doesn’t mean each species lives in that entire range. For instance, some species will live in the mountains of a distribution range but not in lower elevations in that same geographic area.

Critical information

Christopher Parkinson, a professor in the College of Science’s Department of Biological Sciences and Rautsaw’s adviser, said having an accurate range map provides critical information for researchers, medical professionals and citizens alike.

“In the U.S., range maps are pretty accurate, but they are still a living thing,” he said. “With global climate change, we’re seeing ranges change over time. With accurate maps, we can document species movements. These maps also help medical professionals have an idea of their local snake species and allow us to understand what forces help shape a species’ venom.”

Rautsaw will update distribution maps based on feedback from species experts. Additionally, he can project species distributions using future climate models. He hopes to make edits every few years to modify and add distributions

Educational tool

Rautsaw said the maps, which he hopes to edit every few years based on feedback from experts in the field and future climate models, can also be an educational tool for the general public. “They can facilitate interest in snakes and discussions about how important snakes are to the ecosystem. We want people to be aware of snakes, not be afraid of them.”

The journal Scientific Data published details of Rautsaw’s research in a paper titled “VenomMaps: Updated species distribution maps and models for New World pitvipers (Viperidae: Crotalinae).”

The College of Science pursues excellence in scientific discovery, learning, and engagement that is both locally relevant and globally impactful. The life, physical and mathematical sciences converge to tackle some of tomorrow’s scientific challenges, and our faculty are preparing the next generation of leading scientists. The College of Science offers high-impact transformational experiences such as research, internships and study abroad to help prepare our graduates for top industries, graduate programs and health professions. clemson.edu/science

Get in touch and we will connect you with the author or another expert.

Or email us at news@clemson.edu