June 6, 2024, marks the 80th anniversary of D-Day landings along the Normandy coast during World War II. Lifelong Tiger and reporter Wright Bryan made history that day, too, by broadcasting “the first hour” of his eyewitness account.

Did you know the first voice America heard from the frontlines on D-Day belonged to a Clemson man?

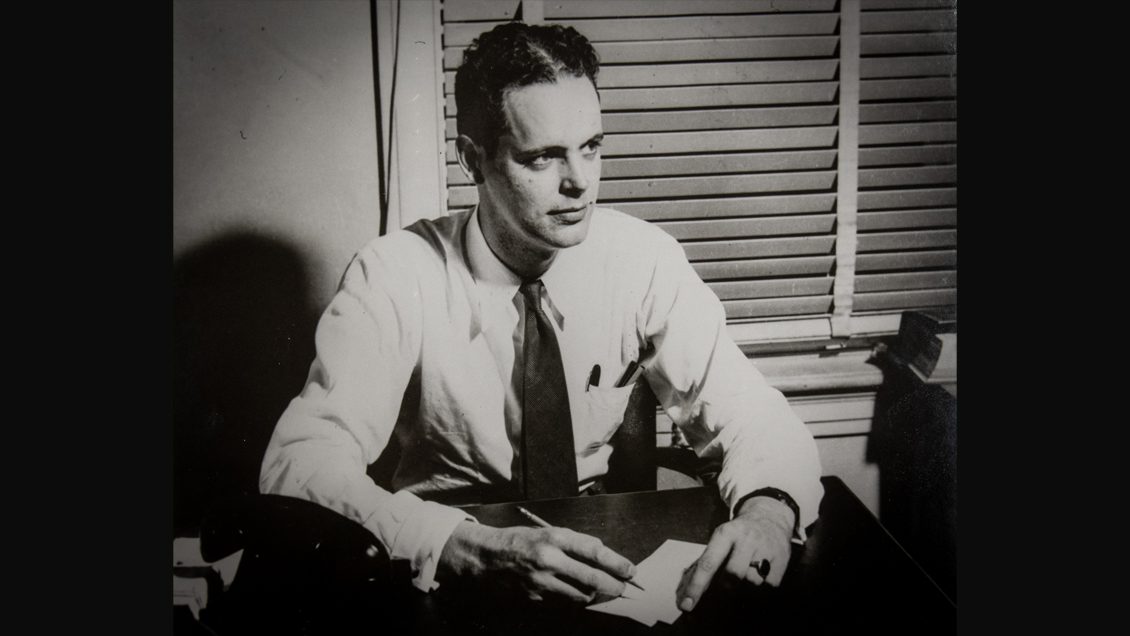

Wright Bryan was a distinguished journalist, University administrator and historian whose love for Clemson spanned his entire life. A 1926 graduate, Bryan literally grew up on the Clemson campus. His father, Arthur Buist Bryan, enrolled in Clemson in 1890 (one year after the doors opened), graduated in the second class in 1898, and was a faculty and staff member for 47 years.

After getting his first professional experience in journalism at the Greenville Piedmont, Bryan joined the Atlanta Journal staff in 1927. He had worked his way up to managing editor/associate editor when he left his executive position in September 1942 to cover the war in Europe for The Journal, Atlanta radio station WSB and NBC.

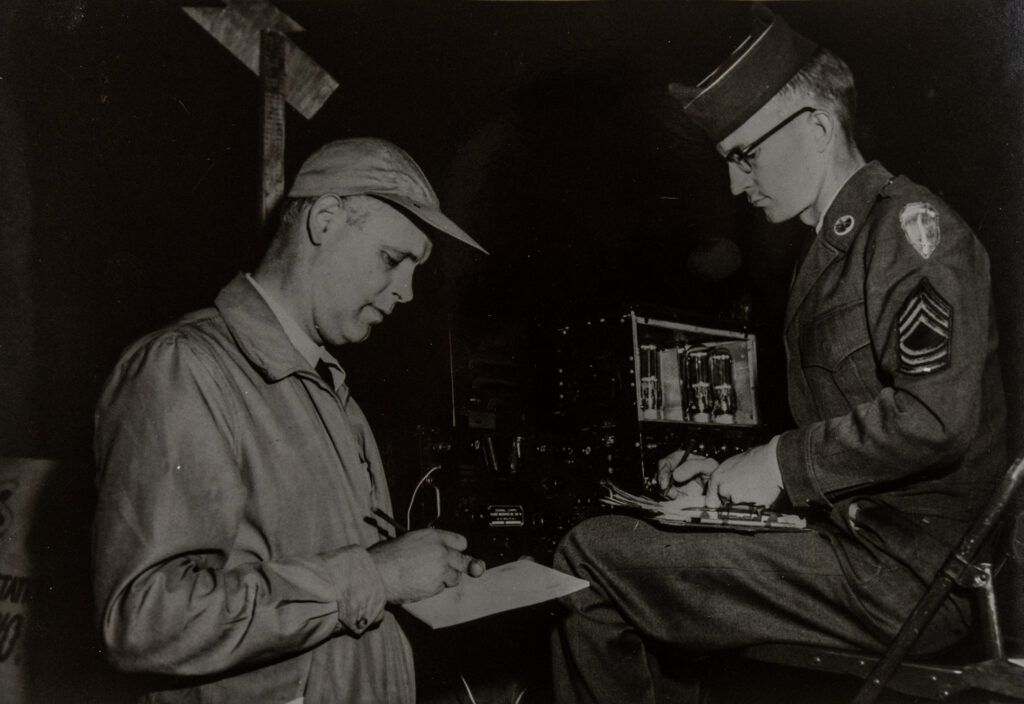

Gen. Dwight D. “Ike” Eisenhower, commander of Operation Overlord, the code name for the Normandy invasion, believed that “an informed public will help win the war.” Bryan was enlisted to help accomplish that mission.

Eighty years ago, on June 6, 1944, Bryan made history by broadcasting the first eyewitness account of D-Day after jumping at the chance to fly over Normandy from southern England’s Greenham Common airfield in a C-47 transport plane with paratroopers from the 101st Airborne Division.

In the early morning, the plane took off and flew over the moonlit English Channel, where more than 5,000 allied ships were driving towards the French shores. The plane was at the tip of the spear of the more than 11,000 aircraft that were mobilized to provide air cover and support for the invasion.

As they reached their designated drop zone over Normandy, Bryan watched as the paratroopers quietly jumped out the back of the plane and floated to the ground — the first Allied soldiers to set foot behind enemy lines that fateful day and the beginning of the end of Germany’s brazen attempt to take over the world.

The plane doubled back to England after spending just 11 minutes over France. Bryan furiously typed out a 10-page, double-spaced radio script at the Ministry of Information in London. Other correspondents on the beaches couldn’t get back, so he was about to scoop more than 600 reporters on one of the century’s biggest stories.

Shortly after 9:33 a.m. in London — the prearranged time for revealing that the invasion had begun — Bryan made his broadcast, following a one-sentence announcement by the Allied command and tape-recorded statements by King George VI and President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

“This is Wright Bryan speaking from London,” he began in his distinct Southern accent. “In the first hour of D-Day … the first spearhead of Allied forces for the liberation of Europe landed by parachute in Northern France. In the navigator’s dome of the flight deck of a C-47, I rode across the English Channel with the first group of planes from Troop Carrier Command to take our fighting men into Europe.

“Just before we left French soil for the return trip to England, I watched from the rear door of our plane, named ‘The Snooty,’ as 17 American paratroopers led by a lieutenant colonel jumped with their arms, ammunition and equipment into German-occupied France. Our group at the head of the leading wing from the U.S. Ninth Air Forces Troop-Carrier Command was met with only scattering small-arms fire from the fields, which were dark and quiet as we entered enemy territory. As we headed back toward the English coast, we saw tracers arching through the air behind us and a steady parade of Allied planes moving out over the course we had just navigated to strengthen the ground forces we had left below.”

Bryan’s masterful report continued for another 12 minutes, describing not just the harrowing flight to and from Normandy but the week in the camp leading up to it and the shifting mood among the soldiers as the day approached. At one point, he described how one of the paratroopers stumbled in the rush to get out of the plane and, missing the window to jump, was inconsolable as he had to ride back to England with Bryan and the crew.

The broadcast had audiences from coast to coast leaning toward their radios from the edges of their seats.

Telegrams from dignitaries and competing newspapers congratulating Bryan on his scoop filled 13 columns of The Journal the next day. Later, he received one from President Roosevelt, who called Bryan’s report “a grand piece of work.”

Bryan, ever the Southern gentleman, remained modest about getting the big story throughout his life.

“I saw the paratroopers jump, saw ground fire, and that was about the extent of what I saw,” Bryan said in a 1984 interview with The Greenville News.

Bryan, whom The Journal described as “an imposing man who stood 6 feet, 5 inches tall,” continued to report on the war in France until he was wounded and captured by the German army on September 12, 1944. He spent six months in hospitals and a prisoner-of-war camp in Szubin, Poland, until Russian troops freed him on January 21, 1945.

He returned from the war a hero and was named editor of The Journal. In 1947, Eisenhower awarded him the Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor.

He was president of the American Society of Newspaper Editors in 1953. In 1954, he left The Journal after 27 years to become editor of the Cleveland Plain Dealer. He was editor of the Plain Dealer from 1954 to 1963 before returning to Clemson University to be vice president for development from 1963 to 1970.

He never lost his keen interest in his alma mater, serving as the president of the Alumni Association in 1958 as well as being on the board of the Clemson University Foundation. He had the distinction of delivering the commencement address at Clemson College in 1946 and 1956. He was awarded an honorary Doctor of Laws degree at the 1956 ceremony.

Upon retirement, he continued living in Clemson and devoted himself to researching and writing his book “Clemson: An Informal History of the University 1889-1979”, still considered one of the seminal accounts of the University’s history.

In 1987, Clemson University awarded Bryan the Clemson Medallion, its highest honor.

Bryan passed away in 1991.