Associate Professor Joshua Catalano was looking to discover the outline of Fort Rutledge, a Revolutionary War fort on Clemson’s campus, when he located the organic matter that changed Clemson’s historical record.

In the spring of 2018 Catalano, a scholar of the American Revolution, was invited to a meeting with Historic Properties. The team was discussing historical sites on campus, of which they noted Fort Rutledge. At that meeting Catalano met his soon-to-be research partner David Markus, and the pair bonded over the same question: why is there a revolutionary war battle site on campus that no one is talking about?

When the COVID-19 pandemic ended out-of-town research projects for both professors, they decided to explore the history in their own backyard.

History of Fort Rutledge

Fort Rutledge sits near what used to be the Cherokee town of Esseneca (where modern-day Seneca gets its name). Today the village is submerged under Lake Hartwell.

On August 1, 1776, the South Carolina militia came through the town of Esseneca, wrongfully assuming that the place was vacant. British and Cherokee forces sprung a trap and a small battle happened, which we’ve come to know as the Battle of Esseneca. The militia later came back and destroyed the village before establishing a fort. In 1780, the fort was surrendered to the British and destroyed.

Nothing was left of the fort, not even a drawing or written description. Catalano and Markus hoped to find the boundaries of the fort. They discussed project collaboration with the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, set up a field school, recruited students to participate and began digging.

Finding Lost History

“We didn’t know it at the time, but at our first field school we were already a thousand years before the revolution,” Catalano explained. “Farming equipment and construction had taken the top layer of soil off.”

The team’s research question changed after realizing the bounds of the fort might be geologically lost. What they did discover led to even more questions about Clemson’s history.

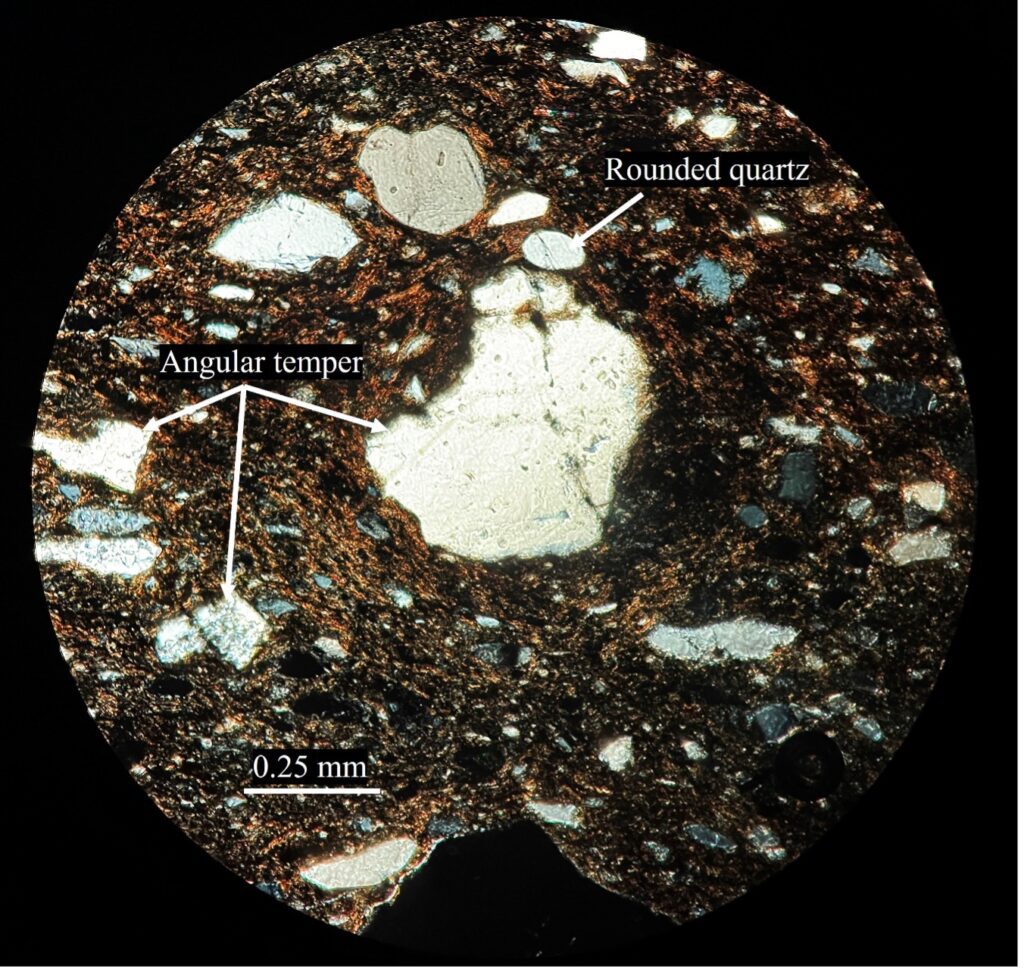

The team kept finding old pottery pieces and stone points used for hunting in the soil. Organic matter in the pottery returned a radiocarbon date of 677–873 A.D. Previously, the earliest historical record of human settlement on the land that later become Clemson dated back to 1720.

“For us, this is the earliest piece of history we now know about Clemson,” Catalano explained.

A Collaborative Community

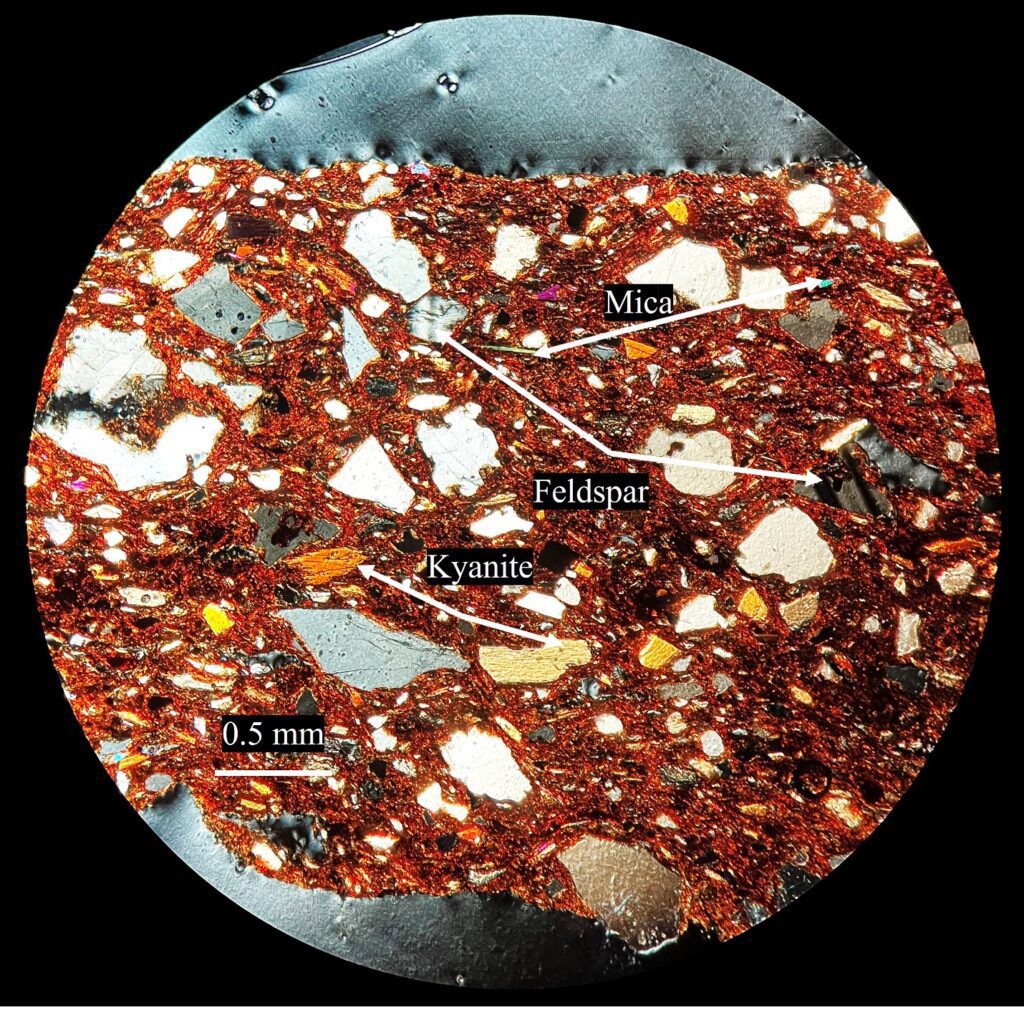

As postdoctoral fellow C. Trevor Duke studied the pottery under a microscope, the team noticed that, despite being made in a variety of Indigenous art styles, the pieces were made from local clay.

“Underneath what we thought was going to be a whole study of a revolutionary war fort we find this meeting place of different indigenous cultures all bringing their own styles of pottery and techniques, but all using local clay, which means they were making things here, together,” Catalano said. “Long before there was a university bringing people from all over the world together here, people have been gathering in this place for thousands of years.”

To Catalano, these findings indicate that people knew the land we now know as Clemson as a place where they could gather, hunt and rest together.

One of a Kind Student Experience

Catalano and Markus knew they wanted to invite students into this experience. “Because how cool is it to literally unearth your campus’ history?” Catalano remarked.

Students in the field school participated in every aspect of the project. They began by learning the basics of archeology, specifically how to document each step of the process. “It’s the most important thing,” Catalano explained. “If we lose the context of where we found something, we lose it all.”

Students learned how to mark units, properly dig and scrap the soil, sift through soil layers and document the findings. They made 3D coordinates of each dig site to get a visual representation of their findings and learned how to process their findings in the lab.

The field school was an educational catalyst for many students.

“A few students wrote research papers, and a lot of the students went on to get jobs in cultural resource management firms,” Catalano said. “A few of them went to graduate school. There was a lot of success from the project on the student end.”

From modern-day work on collaborative research projects to ancient agreements of cohabitation, Catalano’s work has affirmed the adage about this land: there really is something in these hills.

Those interested in pursuing similar projects are encouraged to explore undergraduate history and archaeology courses offered by the Department of History and Geography and the Department of Sociology, Anthropology and Criminal Justice. Graduate students can explore options offered through the Digital History Ph.D. program.