Clemson research suggests revision to endangered seabird’s marine range

The devil is in the details, and for the seabird known as the “little devil,” one significant detail — a consensus on its geographic marine range — has long proven difficult to pin down.

But in a recent paper, Clemson University scientists suggested the marine range of the globally endangered species with the nefarious nickname be modified after the birds were observed throughout the northern Gulf of Mexico during a series of at-sea surveys.

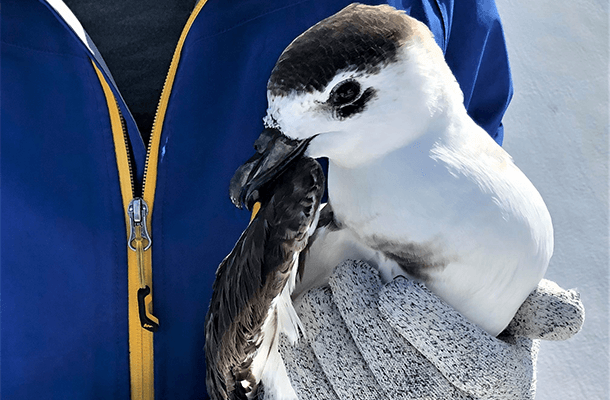

The black-capped petrel, known on Hispaniola as “diablotín” or “little devil” because of its eerie call and the sound produced by air moving over its wings during nocturnal flights, is endemic to the western north Atlantic region — or above the equator on the North American side of the Atlantic Ocean — and the only known breeding sites are at a few locations in Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

Due to limited data, however, there is currently no consensus on the geographic marine range of the species and none of the currently proposed ranges included the Gulf of Mexico — until Clemson’s recent publication.

Clemson Professor Patrick Jodice, leader of the S.C. Cooperative Research Unit, said, in general, marine birds tend to be less well studied and less understood than other groups of wildlife due to the difficulty of working in a marine environment and the birds often being hundreds or thousands of miles out to sea.

“The advancement of technology has allowed us to track birds in a way we haven’t been able to before; there are a lot of marine birds for which the ranges are being reimagined or revised,” Jodice said. “Black-capped petrels have turned out to be one of those.”

That’s due in large part to vessel-based survey efforts throughout the northern Gulf of Mexico from 2010−2011 and 2017−2019. Across 558 days and almost 34,000 miles of surveys, 40 black-capped petrels were tallied. While most observations occurred in the eastern Gulf, birds were observed over much of the east−west and north−south footprint of the survey area.

The recent surveys were supported by the Gulf of Mexico Marine Assessment Program for Protected Species, which aims to provide information to the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management for regulatory needs, as well as other agencies and stakeholders involved in effective management and conservation of Gulf protected species. The earlier surveys were conducted as part of the Deepwater Horizon response effort.

After the extent of occurrence and area of occupancy were used in predictive models to delimit the geographic range of the species within the northern Gulf, Jodice and his team suggested in publishing their findings that the marine range for black-capped petrels be modified to include the northern Gulf of Mexico.

Clemson Post-Doctoral Research Associate Pamela Michael, one of the paper’s co-authors, said revising the range of an endangered species helps understand the potential threats it could encounter while at sea.

“Improving the understanding of the areas where black-capped petrel occurs can also help identify opportunities to protect this species, including creating collaborations with local communities, researchers, managers and other organizations concerned with the persistence of this unique species,” Michael said. “Even with species that are easy to see, it can be challenging to understand where they may go in a day, month or year. This challenge can be even greater when studying a species that can travel great distances … and not leave footprints.”

Black-capped petrels nest relatively high in the mountains. And while many think of Hispaniola, as with the Caribbean in general, as filled with sandy beaches and clear water, it also contains extreme elevations — such as Pico Duarte in the Dominican Republic, which rises to over 10,000 feet above sea level.

“They nest high up in pine forests on Hispaniola. When I was there a couple years ago, we were up at 7,000 feet and they’re in these high-elevation forests, down in these ravines, and they nest in burrows that they excavate or natural holes that they find,” Jodice said. “So, you’re walking around a forest floor where you’re literally crawling under vegetation because it’s so dense in places and you’re looking for a (small) hole that a bird might be in. They come into the nest at night, so they’re not easy to see, and they don’t make any noise when they come in for the most part.”

Still, only about 100 black-capped petrel nests have been located at two sites in Haiti and three sites in the Dominican Republic. And while there is some evidence the species may be breeding in other places such as Cuba and Dominica, that has yet to be confirmed.

The species was believed extinct until the mid-1960s when nests were found on Hispaniola. Scientists consider the breeding population to be between 2,000-4,000 individuals, or 500-1,000 breeding pairs, though the limited nests located in the ensuing 50-plus years makes even that figure a rough estimate.

“To be honest, it’s still a big deal when we find a nest,” Jodice said.

Thus, much of the focus from a conservation standpoint has been on land — finding nests and protecting those nests — since the nests are subject to human influence such as deforestation and losing an adult in a nest means losing significant reproductive potential for the species.

But following seafaring surveys done in the Atlantic in the 1980s and continuing into the 1990s and 2000s, it was determined that the core of the black-capped petrel’s marine range was the Gulf Stream of the Atlantic Ocean.

Through the whole process of nesting, from incubation through rearing a chick, the birds make regular trips to sea to forage, and conventional wisdom among scientists suggested they were going back and forth between Hispaniola and the Gulf Stream off the coast of North Carolina. Other research conducted by Jodice’s lab showed that they also were frequenting waters of the Caribbean Sea while raising their chicks.

But while the Gulf of Mexico was considered an area where the birds would occasionally visit or wander — as seabirds are wont to do — their presence was believed to be uncommon.

“It was like, ‘Yeah, you might see them there, but I wouldn’t bet on it,’” Jodice said.

What the research published by Jodice and his team showed, however, was that the species can be found in the Gulf on a regular basis and occurs throughout its entire east-west footprint. The surveys were restricted to the northern half of the Gulf, the U.S. exclusive economic zone (EEZ), where the U.S. has jurisdiction over natural resources.

“Through the surveys we did in 2017-19, we saw enough petrels to think, ‘There’s something going on here. They’re here more regularly than we thought; they’re spread out more than we thought,’” Jodice said. “Then we went back and looked at the surveys from 2010-11 when a colleague was doing surveys during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. I think he found eight or nine petrels during those surveys, and he said, ‘I wasn’t sure what to make of those, but now that we’ve got these three years of data … these fit right in.’ It’s kind of like a jigsaw puzzle. Now it made sense.”

Michael’s role was designing and running the statistical analyses that contributed to the revised range description. These models aim to improve the understanding of where species go and what habitats they use.

“It can also be nerve-wracking because I know that people and agencies will look at our results and potentially use them to make important decisions,” she said. “This is where my favorite part of research comes in: co-workers and collaborators. The work that produced the revised range of this species was the synergy of the knowledge and experiences of our co-authors and co-workers and official reviewers who evaluated this study before it was published. Everyone contributed unique insights, leading to some thoughtful conversation and increasing the quality and relevancy of our research.”

That gave the scientists evidence to espouse that the Gulf of Mexico should be considered part of the black-capped petrel’s marine range, something that — although models vary — hadn’t been the case before.

“Given that the species is globally endangered and we know of so few birds and, given that the species is currently being considered for listing under the Endangered Species Act by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, we thought this was a good opportunity to put out there all the data that we have … and say, ‘Here’s what we found. Here’s what we think is going on. The data we’ve got suggests that the Gulf of Mexico should be considered part of the range,’” Jodice said.