Editor’s Note: The monthly “Elevate Well-Being” blog series shares thoughts and reflections of Clemson Well-Being Council members and University faculty, staff and students. Our latest blog is courtesy Patricia Whitener, 4-H Natural Resources Programs Leader and Wellness Ambassador for the College of Agriculture, Forestry and Life Sciences.

I am an environmental educator. When I share that with people, I can see the slight cock of the head as they try to decode what it means. Some imagine a teacher, a camp counselor, perhaps even a park ranger or tour guide — roles I have held at various times. Today, my job title as 4-H Natural Resources Programs Leader at Clemson University, within the College of Agriculture, Forestry and Life Sciences, reflects an evolving purpose.

I have guest lectured for classes in a variety of degree programs — Education, Parks, Recreation and Tourism Management, Food, Nutrition & Packaging Sciences, and Agricultural Education. My teaching has spanned K-12 public classrooms, Montessori, charter, private schools and homeschool groups. I’ve spoken for local garden clubs and Master Gardener & Master Naturalist programs, both certified through Cooperative Extension. As an Extension Associate, my honor is profound: I help fulfill the land-grant mission by serving communities across South Carolina and representing Clemson University far beyond geographical boundaries.

In my daily work, I strive to educate, connect and inspire people to forge meaningful relationships with their environment, encouraging them to become better stewards of our natural resources. “Environmental Educator” might describe what I do, but it hardly captures the essence of who I am or why I do it. This distinction — defining ourselves by what we do versus who we are — is central to how I view my purpose and the land I share with others. There is a large body of research supporting the numerous benefits of a connection with nature and how that connection “supports happiness and [helps us lead] more purposeful, fulfilling and meaningful lives” (Zylstra et al, 2014).

Aldo Leopold, in his landmark work, “A Sand County Almanac,” transforms this professional calling into a guiding philosophy: “We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.”

Through this lens, I see my role not solely as an educator or facilitator, but as a fellow member of the community — engaging in its integrity, stability and beauty. It brings me great joy to be out in our environment. When I engage in the soil, waters, fauna, flora and people, I feel most connected to the organization where we work.

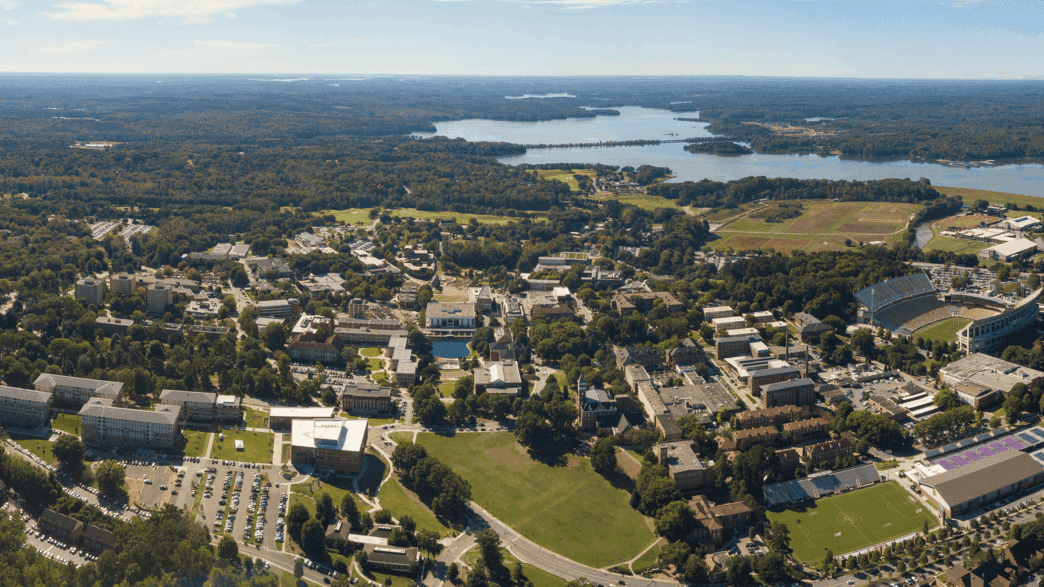

My work at Clemson, both on and off the campus, asks participants — children and adults alike — to see themselves as part of this living community, not merely consumers of its benefits. Clemson University’s campus, rich with green spaces, offers daily opportunities to practice Leopold’s ethic and enhance our well-being. From the serenity of the South Carolina Botanical Garden to the leafy refuges along the Walker Golf Course trails and the Carolina blue waters of Lake Hartwell in the Clemson University Forest, one need not look far for a place to step away from the screen, take a breath and remember our bond with this place. These spaces are not incidental — they are intentional invitations to pause, observe and renew one’s sense of membership in a complex, beautiful and shared community.

“There is profound beauty and connection to be found in developing a personal relationship with our environment,” Aldo reminds me, and anyone willing to listen. If you wander across Clemson’s campus, you’ll discover not only meticulously manicured lawns and flowerbeds, but also wild edges, pollinator gardens, arboretums and restored woodlands — living lessons in stewardship and reciprocity. In every class I teach or program I lead, I encourage others not only to recognize these landscapes, but to appreciate their role within them.

Ultimately, as Leopold so beautifully concludes, “That land is a community is the basic concept of ecology, but that land is to be loved and respected is an extension of ethics.” At Clemson, our green spaces are more than scenery; they are essential to our well-being, classrooms without walls, refuges for reflection and living proof that how we care for the land shapes who we are. Environmental education here is not a job title, but a daily act of belonging. So, I encourage you to look at this place we call “work” and think about it as a community where you too can engage in this amazing environment and make it part of your philosophy as well.