Nestled on the edge of the City of Seneca in Oconee County, South Carolina, the Perry Hill and Utica Mill Communities have enjoyed a thriving past, but have struggled in recent years.

“When the mill left here, it created a lot of issues that have affected the community,” said Seneca Mayor Dan Alexander. Then in 2020, a tornado struck.

“The whole scope of it is natural disaster, economic development, and quality of life. Definitely, the storm played a major role and put us farther behind,” he said.

Blue Ridge Community Center, located in what was formerly Blue Ridge High School, serves as a hub for the neighborhood. Before desegregation, it was the “colored” school for minority students in surrounding communities. Today, it’s where Helen Rosemond-Saunders and other volunteers work to ensure that community members stay connected.

“This is home,” says Rosemond-Saunders, who taught at the school for decades. “This is my heart.”

In 2019, community leaders saw a huge opportunity for the area—literally—when it was designated as an Opportunity Zone. Opportunity Zones were established by Congress as a part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, designed to encourage long-term private investments in low-income communities. The program provides a federal tax incentive for taxpayers who reinvest unrealized capital gains into “Opportunity Funds,” which are dedicated to investing in low-income areas called Opportunity Zones. The designation has led to an effort from local government officials to ensure that businesses, companies, and entrepreneurs are attracted to the area.

“We want to take away the reasons for a private investor to say ‘no,’” said Paul Cain, District III Oconee County Councilman and Chairman of the Planning and Economic Development Committee.

The Opportunity Zone designation offered both hope and a challenge for the community and its leaders. They needed to determine not only how to revitalize the area to attract investment, what sort of improvements should be made when investment opportunities came and how to balance the desires of businesses with the needs of residents.

In other words, they needed to do research. Enter the Landscape Architecture program at Clemson University.

Landscape Architecture Professor Hala Nassar’s second-year design studio teaches students to tackle precisely the kind of questions that leaders in Seneca were faced with. In the fall of 2021, she set her students to the task of not only analyzing the community’s needs, but also visualizing design solutions that capitalize on the community assets while addressing problems.

“Landscape Architecture design studio presents a unique opportunity for service learning,” Nassar said. “There are many communities around us that have needs. Addressing community design needs in a studio setting is a win-win.”

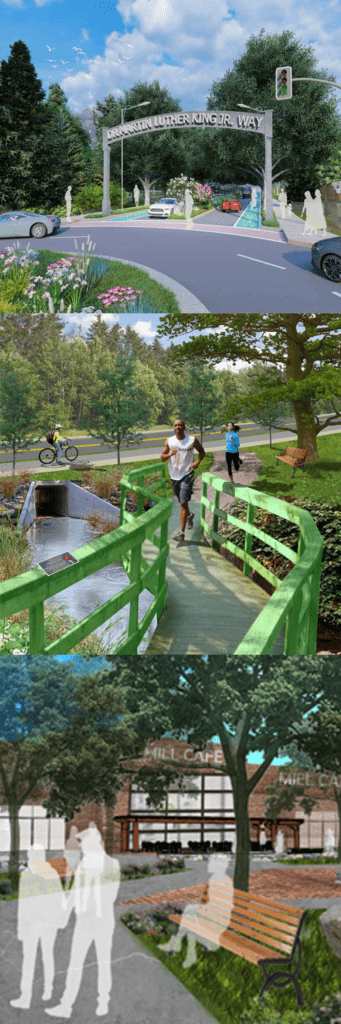

Her students completed a 13-layer analysis of an area encompassing the South 6th Street corridor, which Nassar describes as the “spine” of the Opportunity Zone. The street, recently designated “Dr. Martin Luther King Junior Way,” is central to the area’s cultural past and economic future.

Their research included Geographic Information System (GIS) analysis, historical study, aerial photography, site observation, visual analysis and more. Then, they began to research the most important perspective: the views and opinions of the people who live there.

In September, 2021, the Blue Ridge Community Center opened its doors for what landscape architects call a “charette,” an opportunity for members of the community to give concrete feedback about the kind of changes they would like to see.

“Community is funny, you go out here and you share the information, but you don’t know if they’re going to come,” said Rosemond-Saunders, who promoted the event throughout the neighborhood. “It’s warmed my heart to see the people coming in,” she said. “That means somebody cares. They want to know. They want to get involved, that’s what it says to me.”

For Nassar’s students, it was a chance to see how the design process works in the real world.

“When Professor Nassar showed us the site and I saw that there was an old mill on it, I was so excited because I love the idea of refurbishing brownfields,” said Kinzer Hurt, a second-year landscape architecture major.

Hurt and his classmates set up four stations at the Community Center to garner feedback. The first station was to identify “community assets,” or things that people wanted to preserve. The second was to identify “concerns” that community members would like to see addressed. The third station was dedicated to “opportunity areas,” or new ideas that neighbors would like to see incorporated into future plans. At each of the first three stations, members of the community were given color-coded stickers to mark their ideas on each map, and students took careful notes. At the fourth station, the students administered a survey.

“51 people showed up to tell us exactly what they cared about and what they wanted to see, and I think that was really helpful for future designs,” Hurt said. “A lot of people actually said that they wanted dedicated signs at either side of the street so that people actually know it’s ‘Dr. Martin Luther King Junior Way.’”

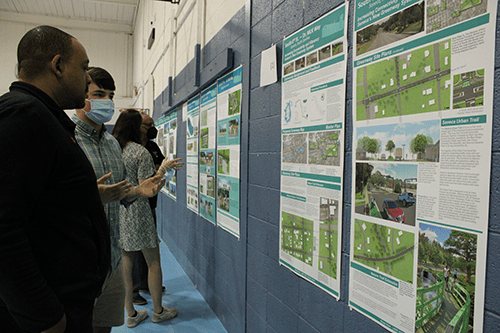

After the feedback session in September, the long design process began for the students. Despite the wide range of potential ideas for improvement, Nassar noted that once students brought the dot maps back to the studio, most of the feedback centered on the same areas. After months of careful work in the studio, students had the opportunity to return to Blue Ridge Community Center in March 2022 to present their designs.

Proposals included a greenway system, commercial plazas to revitalize closed industrial sites, and a stunning new Dr. Martin Luther King Junior gateway. Each design seeks to capitalize on the sites’ current strengths and flows from the feedback of people who know the area best.

“There were 13 different very strong proposals, and when we presented them, they were very well received by people who attended,” Nassar said. “We’ve gotten a lot accomplished in a relatively short time. Community members commended students on their design work. More than one official said they wanted copies of the projects because they can envision them being implemented.”

The students’ design boards were plotted and displayed in the same gymnasium where community members were able to give input. The project fulfills Clemson University’s land-grant mission, providing immediate value to South Carolinians while equipping students with the experience they need to make an impact in the future.

“Not only do they learn design, but they also employ their skills to bring positive change,” Nassar said. “It gives them an extra dimension of understanding the value of the design as an agency for supporting community development.”

About the College of Architecture, Arts and Humanities

Established in 1996, the College of Architecture, Arts and Humanities celebrates a unique combination of disciplines—Architecture; Art; City Planning; Construction Science and Management; English; History; Languages; Performing Arts; Philosophy; Religion; Real Estate Development and interdisciplinary studies—that enable Clemson University students to imagine, create and connect. CAAH strives to unite the pursuit of knowledge with practical application of that knowledge to build a better and more beautiful world.