Shark Week has invoked admiration and fear among Discovery Channel viewers for more than three decades.

As this year’s Shark Week approaches (it’s July 23-29), scientists are fearful, too. Not because of the cultural phenomenon’s portrayal of sharks as one of the world’s most menacing and deadly killers, but because the ocean shark population has plummeted 71 percent since 1970. One of the main causes is overfishing.

A 2021 study found one-third of the world’s shark species are threatened with extinction. Sharks reproduce and grow slowly, and heavy fishing over the past half century has drastically outpaced the population’s rate of renewal.

Connections

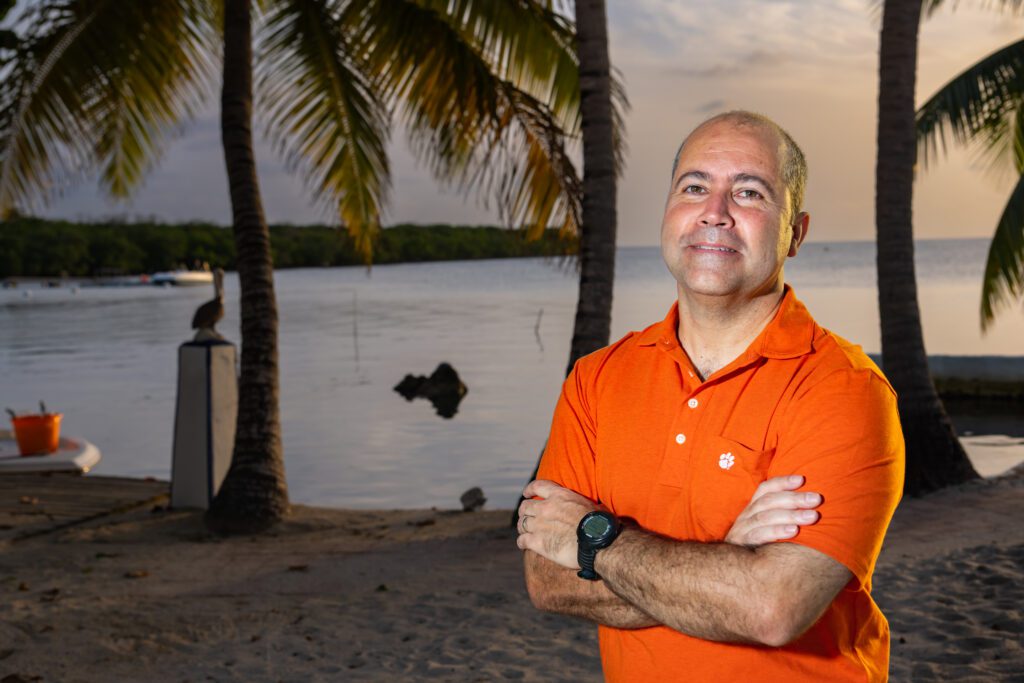

Antonio Baeza, an associate professor in the Clemson University Department of Biological Sciences, and his students are investigating the genetic connectivity among populations of different shark species in and across oceans using mitochondrial genome markers.

Their ongoing research has shown there are long-distance genetic connections among shark populations, even between different hemispheres and across oceans. His and collaborators’ studies indicate the way fisheries are managed needs to change if sharks are to be fished in an environmentally sustainable manner.

“The assumption that fisheries can be managed as independent units doesn’t appear to hold true anymore,” Baeza said. “We cannot assume that if a population is heavily fished in the western Atlantic that there’s no effect in the eastern Atlantic because of this connectivity among populations. These fisheries cannot be managed separately.”

A good example is the porbeagle shark Lamna nasus, a large, highly migratory shark distributed in cold and temperate waters of the North Atlantic and the southern hemisphere.

Baeza said there is a little known but well-developed fishery for porbeagles in the U.S. and in England. In the latter, the species is overfished. The two fisheries on opposite sides of the Atlantic have been managed as independent units for decades, the assumption being that intense fishing in the eastern Atlantic will not cause a decline in the western Atlantic U.S. fishery. Baeza’s data suggests that is not necessarily true because of migration.

In a previously published study, Baeza and his team found the population of the porbeagle sharks in the northwest Atlantic were genetically connected to the population found in the northeast Atlantic.

In a new study, they researched south Pacific Ocean populations of the blue shark Prionace glauca and the shortfin mako Isurus oxyrinchus, two large and highly migratory sharks inhabiting temperate and tropical waters worldwide.

The study showed an overall pattern of high genetic connectivity among hemispheres and across ocean basins with a signature of shallow genetic structuring worldwide. Detailed findings will be in an upcoming issue of the journal Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems.

Not a barrier

“For many shallow water species, smaller bony fish for instance, tropical latitudes act as a barrier for dispersal and stop or decrease the probability of connections among populations via adult dispersal or larval drift. If you think of a little fish that’s born in the cold waters of the north Atlantic, it’s very difficult for these little guys to travel long distances, traverse warm tropical waters, and establish themselves in the south Atlantic. Low dispersal ability and the high temperatures of the tropic limit their ability to travel long distances” Baeza said.

“But sharks can swim long distances for long time periods. They can even swim relatively deep where the waters are not too hot. Tropical latitudes are not necessarily as strong a barrier for several shark species. That’s something that explains, in part, connectivity among hemispheres for sharks,” Baeza continued.

Other than understanding long-distance connectivity among populations of imperiled sharks, the Baeza lab is generating genomic resources for endangered sharks and rays.

Students are assembling and analyzing in detail mitochondrial genomes for other species of sharks and rays as a part of Baeza’s Creative Inquiry program. These resources are likely to be instrumental for biomonitoring and bioprospecting of shark and ray populations impacted by human activities using state-of-the-art environmental DNA.

For a long time, we’ve known a lot about how to fish for sharks, but relatively speaking, we know very little about sharks.

Antonio Baeza, associate professor in the Clemson University Department of Biological Sciences

“For a long time, we’ve known a lot about how to fish for sharks, but relatively speaking, we know very little about sharks. Why? For many years, there was a lack of interest. Now, we know that they are important, and there’s more of an effort to try to understand them,” Baeza said. “There’s plenty more to know about these iconic marine vertebrates that are heavily impacted by human activities and global change.”

Get in touch and we will connect you with the author or another expert.

Or email us at news@clemson.edu