As sunseekers flock to South Carolina’s coast for summer, the alligators that call the Lowcountry home and play a vital role in its ecosystem also begin to bustle with activity.

So, while hurricane season is still several weeks away, a perfect storm is already brewing when it comes to chance encounters between the two groups.

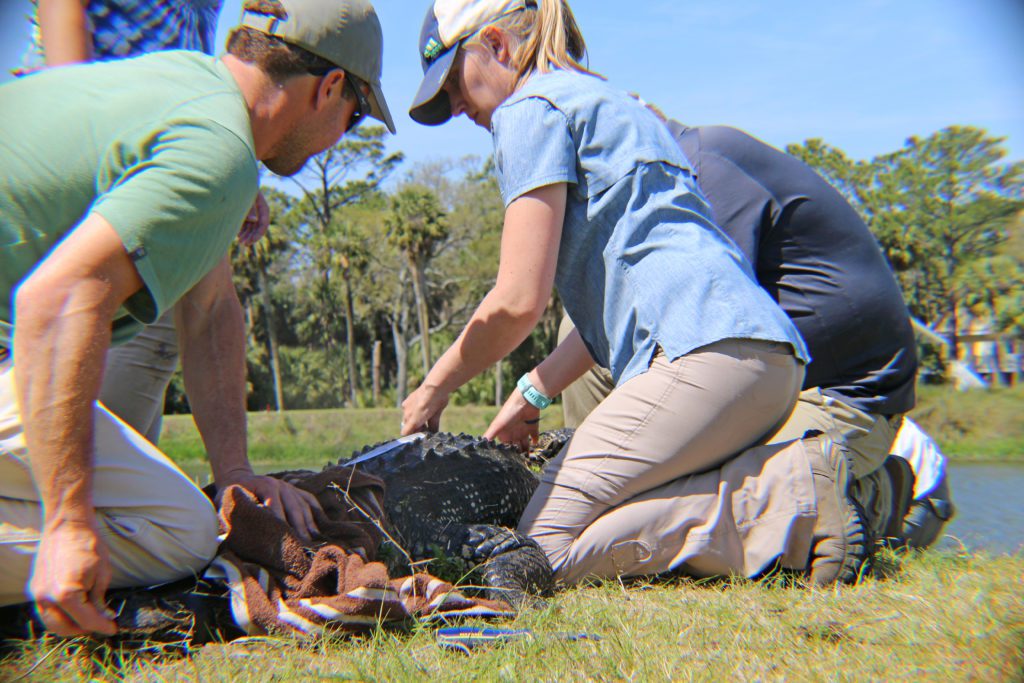

And with urban sprawl and human encroachment on the rise, Clemson University scientists are looking for novel ways to mitigate those interactions — specifically, studying whether capture-and-release protocols are effective in reducing alligator tolerance of humans.

The data from this aversive conditioning, researcher Anje Kidd-Weaver says, is promising.

“While it seems we can teach alligators to be warier of humans, that is only half the battle.”

Clemson Researcher Anje Kidd-Weaver

“Alligators are learning to live with humans, but whether they learn to be tolerant or wary of humans depends on human behavior,” she said.

In a research article published recently in The Journal of Wildlife Management, Kidd-Weaver and collaborators measured the behavioral response to an approaching human of South Carolina alligators with three different levels of capture experience and compared the animals’ responses and likelihood to flee.

On Fripp Island, where captures did not occur during the study, the team found the youngest and smallest alligators were most likely to flee from humans and the probability of flight decreased as alligator size — and age — increased. For example, alligators measuring just 3 feet long moved away from people about 50% of the time, while 6-foot-long alligators fled only 20% of the time, and 10- or 12-foot-long alligator fled on only 10% of occasions.

Simply, the animals became more comfortable around humans and less likely to flee with age.

“In a place where alligators are having primarily benign encounters with humans, these data appear to support our hypothesis that alligators are learning to be increasingly tolerant of humans over time based on the nature of their interactions with humans,” Kidd-Weaver said.

On the flip side, on Spring Island, where scientists spent 9 years capturing and releasing alligators — there was consistently an 80% or greater chance that an alligator would flee from an approaching adult human, and larger and older alligators were the most likely to flee.

Significantly, in this scenario, adult alligators were nearly 100% likely to flee from approaching humans.

“Rather than alligators learning to be tolerant of humans, it appears that they are learning to be warier of humans when their interactions are stressful,” Kidd-Weaver said.

The researchers also found that exposing alligators to capture-and-release doesn’t just increase the likelihood that they will move away from people, it also seems to determine how close they will allow humans to get before fleeing.

“Among alligators that did flee, we found that size and experience was a predictor of how close they would allow a human to approach,” Jachowski said. “Small alligators, less than 3 feet and not having lived around humans for long, typically allowed us within 20-30 feet before they fled, regardless of whether they had witnessed or experienced capture.

“Larger and older alligators — measuring 8 or more feet — that had never been exposed to aversive conditioning typically allowed humans to approach within 30 feet, while those that had been exposed to capture-and-release for several years rarely allow humans within 120 feet before fleeing.”

PART OF THE PROBLEM

Humans and alligators have lived in proximity for decades and only four alligator-related human fatalities in South Carolina have been recorded, but all have occurred in the past six years — at least preliminary evidence to suggest attacks are increasing in South Carolina.

Cathy Jachowski, an assistant professor in Clemson’s Department of Forestry and Environmental Conservation, said while she suspects a large part of the population “likes the fact that alligators are there and enjoys or values” their presence, she also knows more incidents can change those attitudes quickly.

“There’s probably also a very vocal minority that may have a problem with their presence,” she said, “and that minority may grow as the demographics of those regions change. If nothing is done, the likelihood of negative alligator/human interactions occurring is probably going to increase.”

Jachowski said in terms of management, alligators in South Carolina occur in drastically diverse areas — from extremely rural areas and wildlife preserves on one end of the spectrum to bustling coastal golf course communities on the other.

“The areas where the most complaints originate are the areas that are growing the fastest, those coastal residential areas, Beaufort County specifically,” she said. “So, people are coming there and many of them have never been around alligators before and may not know that there’s a risk of an alligator showing up in their backyard until they’ve been living there for a while. So, it can come as a surprise.”

As with other reptiles, cold weather limits the ability of alligators to feed and move around. They become more active as the temperature warms up, as they court and breed from May to June — when males can be territorial and compete for female attention — and females attend nests from June through August.

Tourism is South Carolina’s biggest industry, worth nearly a quarter-trillion dollars to the state in 2019 and driven by coastal destinations such as Charleston, Myrtle Beach and Hilton Head, meaning the Lowcountry is bustling with humans while alligators are also at their most active.

“Humans are not part of the alligator’s natural diet,” Jachowski said. “An adult human is larger than most prey items an alligator would take down, while children and pets definitely fall within the range of potential prey-sized items for large alligators, which can take deer.

“But we also know that humans often feed alligators — despite it being illegal to do so — and we also know that alligators learn from their experience. So, illegal human actions are one possible reason why an alligator might begin associating humans with food.”

And feeding alligators is just one of the very bad ideas humans sometimes have when it comes to interacting with the massive reptiles. In early August, The (Hilton Head) Island Packet reported three teenagers, “driven by boredom,” captured an alligator with a makeshift slipknot in a nylon rope. The three teens involved were issued citations from the S.C. Department of Natural Resources totaling $260 each.

LOOKING FOR SOLUTIONS

That combination of factors is why Jachowski, Kidd-Weaver and their collaborators have been studying the effectiveness of capture as aversive conditioning for American alligators in human-dominated landscapes and, ultimately, led to the recently published paper with Clemson alligator expert Thomas Rainwater and retired S.C. Department of Natural Resources (SCDNR) scientist Tom Murphy.

SCDNR alligator biologist Morgan Hart said the research Clemson is leading on human/alligator interactions is especially important as human populations in the Lowcountry and surrounding areas continue growing rapidly.

“More people are moving into areas where alligators already live, which can increase the likelihood of encountering an alligator,” Hart said. “The more we know about alligator behavior in human-dominated landscapes, the better equipped we are to handle alligator issues before they become dangerous.

“The research done by Clemson has the potential to impact the way alligators in urban areas are dealt with in South Carolina.”

SCDNR Biologist Morgan Hart

And the research is not just of interest to the scientific community, as municipalities and other communities around South Carolina have partnered with Clemson to help alligators and humans coexist more harmoniously in the state.

The recently published article also traces the project’s smaller-scale beginnings to Spring Island, a 3,000-acre nature preserve and island residential community in Beaufort County where retired SCDNR biologist Murphy and George Rock spent nine years studying its alligators.

On Spring Island, a 3,000-acre nature preserve and island residential community in Beaufort County, retired SCDNR biologist Murphy and George Rock spent 9 years studying its alligators.

Over the course of the study, Murphy and Rock concluded tagged alligators showed a greater flight distance than was observed at the onset of the study — in layman’s terms: alligators that had been captured and tagged would not let people get as close as they would before capture.

Working with Murphy, Spring Island Trust Director Emeritus Chris Marsh investigated ways to expand the result of Murphy and Rock’s work on Spring Island.

“We approached then Nemours Wildlife Foundation Executive Director Dr. Ernie Wiggers, who reached out to Clemson to help spearhead the expanded project that used six sites including continuing work at Spring Island,” Marsh said. “Since Spring Island had already been doing this research for 9 years, we had already solved our initial problem, that being drastically reducing negative alligator/human interactions by making the alligators more wary of humans. The next question was could this methodology be applied in other communities.”

BOOTS ON THE GROUND … AND GOLF COURSES

Other coastal communities in the Palmetto State had been already looking for the same answers.

Sea Pines, a 5,000-acre community on Hilton Head Island with private neighborhoods as well as a resort, PGA Tour golf course and more, became involved in the project though a meeting between Director of Special Projects and Operations David Henderson and Clemson Research Scientist Thomas Rainwater at a 2017 alligator symposium.

Henderson said because little scientific information existed on alligators in developed areas, Sea Pines Community Services Associates, Inc., had already been working to glean whatever information it could on the topic.

“Sea Pines Community Services Associates, Inc. is proud to partner with Clemson University in its continued efforts to research how humans and wildlife can live harmoniously in developed/populated areas,” he said.

Jachowski gave much of the credit for the early genesis of project to Wiggers, who approached her as a relatively new faculty member at Clemson about the project and worked to bring the private partners on the project together.

Thus, the goals of the Spring Island project were expanded into a broader project to include Sea Pines and Fripp and Kiawah islands, as well as wildlife areas in the state, and Murphy’s existing research gave Clemson’s researchers a significant body of pilot data to work with.

But while the research began with the intent of tracking alligators by GPS, Jachowski said it quickly “expanded and morphed from some of those early ideas.”

While the project relies on hard data, Kidd-Weaver said she gleaned plenty of observational knowledge from interactions with humans during their surveys, often traversing golf courses and being asked by curious golfers what they were doing.

“We would tell them we’re studying the alligators to understand how they interact with people, how wary they are of us and how close we can get to them before they flee,” she said. “Then I would explain that we were going to be doing this capture project to see if we could teach alligators to be more wary of people, and for the most part, I was really interested in the human side of answering those questions.”

Kidd-Weaver said she generally got one of two responses from people when they learned of her work.

“One was people saying, ‘Well, the alligators aren’t the problem, the people are the problem.’ Their attitude was we shouldn’t have to make the alligators more scared of people; people should be more respectful of the alligators,” she said. “And then I would have people who just said that they literally never considered that an alligator could be in the water when they lean down to pick up their golf ball. So, even just having that conversation of saying, ‘There are alligators out here, and we need to be aware of them,’ was an eye-opening conversation for them.”

THE MORE YOU KNOW

So, while the need clearly exists to expand human awareness of alligators, the study measures the alligators’ actions through two separate major components: movement data from a GPS telemetry data set and flight initiation distance.

“We have expanded flight initiation distance research to other communities to see if the data continues to show that capture and release will increase alligator wariness of people,” Kidd-Weaver said.

In addition, the team monitors 48 transmitters on alligators between Spring Island, Fripp Island, Kiawah Island and Sea Pines, as well as several wildlife management areas including Yawkey Wildlife Center and Bear Island Management Area.

“These two components provide a complementary view of alligator behavior: flight initiation distance tests can tell us how alligators interact with people on the ground — at a fine scale — while the GPS data can teach us how they’re interacting with their environment over broader spatial and temporal scales,” Jachowski said.

While the early data from the recently published article has already filled in knowledge gaps about alligators’ responses to approaching humans, Clemson’s researchers have continued to work since that data was collected to learn more.

In a new aversive conditioning study in Fripp Island, Kiawah Island, and Sea Pines, data showed that alligators’ probability of flight increased from approximately 40% to 60% after the aversive conditioning was implemented.

“With a single application of aversive conditioning, it seems we can increase their probability of flight … but we did not find support for an effect of aversive conditioning on flight initiation distance that we hoped to see. Still, we believe that our results are promising given that alligators were only exposed to one capture event over a relatively short period of time compared to potentially decades of benign experience with humans (as in the recently published study),” Kidd-Weaver said.

Paired with the data of Spring Island versus Fripp Island, these results continue to support the hypotheses that alligators are learning from experiences in their environment and adjusting their behavior in response.

From the GPS tracking study, the scientists are now comparing space use and resource selection of alligators living in wildlife management areas versus residential/golf course communities — and the results have been eye-opening.

“So far, we have learned that alligators in residential communities occupy much less space than alligators living in wildlife management areas,” Kidd-Weaver said.

For example, in the mating season when alligators are most active, the median activity range for male alligators in residential communities was 1.11 square kilometers — a striking contrast when compared to 15.24 kilometers for male alligators in wildlife management areas.

“While the formal resource selection analysis is still in progress, the activity ranges of alligators in residential areas appear concentrated around ponds or lagoons in neighborhoods or in golf courses, sometimes including only a single pond,” Kidd-Weaver said.

And that certainly seems to indicate humans aren’t the only ones in this study who are learning a thing or two.

Get in touch and we will connect you with the author or another expert.

Or email us at news@clemson.edu