As most Clemson University students were settling back on campus for the fall, Dana Nelson set off in the other direction — back to Montana — to continue her education.

With experience working as a biologist with endangered species, Nelson came to Clemson with a clear vision of what she wanted from a Ph.D. program. And as she returned to Fort Belknap Indian Reservation this fall to continue working on swift fox restoration, Nelson said she’s found just what she was looking for.

“I came to Clemson specifically to do this kind of work: to work with Dr. (David) Jachowski and the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute and numerous important partners on this team. It’s given me the opportunity to ask bigger and broader questions and get some important answers for management of species that are going to help folks in the role that I used to have,” said Nelson, a Smithsonian Research Fellow.

Getting those answers, in this case, means being part of a wide-scale reintroduction effort to move swift foxes from parts of their range where they are thriving to Fort Belknap, which, including tribal lands, encompasses 650,000 acres of the plains and grasslands of northcentral Montana where swift foxes have been gone for over 50 years.

The smallest canid in North America, the 5-pound, smaller-than-a-housecat swift fox is native to the shortgrass prairies of North America. But in addition to their importance to the culture and ecology of northcentral Montana, swift foxes also serve as a subtle indicator species of grassland health and function as a mesocarnivore within the ecosystem, meaning they predate upon small mammals but are prey for larger animals.

“They have this really nuanced and important role in the ecosystem. And it’s also important to try to restore them from the tribal and cultural perspective, as the folks who live on Fort Belknap really do value having all the species there that used to be there,” Nelson said.

More than 30 foxes in Colorado and 45 foxes from Wyoming have been trapped thus far to help restore a self-sustaining swift fox population at Fort Belknap in northeastern Montana, with a return trip planned to Wyoming this year.

Led by the Fort Belknap Indian Community and the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute — with support from Colorado Parks and Wildlife, Wyoming Game and Fish, Calgary Zoo, WWF, American Prairie, Defenders of Wildlife, University of Wyoming and George Mason University, among numerous organizations and government agencies contributing to the overall reintroduction program — the ambitious translocation project involved live-trapping the animals near Lamar, Colorado, and Laramie, Wyoming, and then transporting them to Montana.

Smithsonian National Zoo & Conservation Biology Institute Research Ecologist Hila Shamon said the reintroduction project is a perfect example of the power of people.

“We managed to convene over 15 organizations across jurisdictions to work collaboratively for a common goal. The research will advance our understanding of swift fox ecology, it will help connect two portions of swift fox range and it will advance our reintroduction methodologies in general,” Shamon said.

Jonathan Reitz, wildlife biologist with Colorado Parks and Wildlife, said the project seeks to address the absence of the swift fox species across a large swatch of “a landscape where it belongs” and where suitable habitat exists.

“What happened with swift fox is that they were extirpated in Montana and southern Canada mostly due to poisoning when there was a campaign to eradicate coyotes and wolves in those areas. Swift fox weren’t the intended target, but unfortunately those areas lost their swift fox. So, it’s really exciting to be part of a project trying to recover a species in an area where it doesn’t exist currently and adding a component back to the ecology of that system,” he said.

Nelson said multiple tribal members have mentioned how important it is to the reservation to have an “intact species assemblage,” meaning the work is important for multiple reasons.

“First, moving swift foxes to the good habitat that’s on Fort Belknap means that we’re doing our part to prevent any further extinction risk and promoting biodiversity by returning a critter to a habitat where it ought to be. The other really cool thing about the project is that returning a species has cultural importance. It’s returning a species to the sovereign lands of the A’aninin and Nakoda nations,” she said.

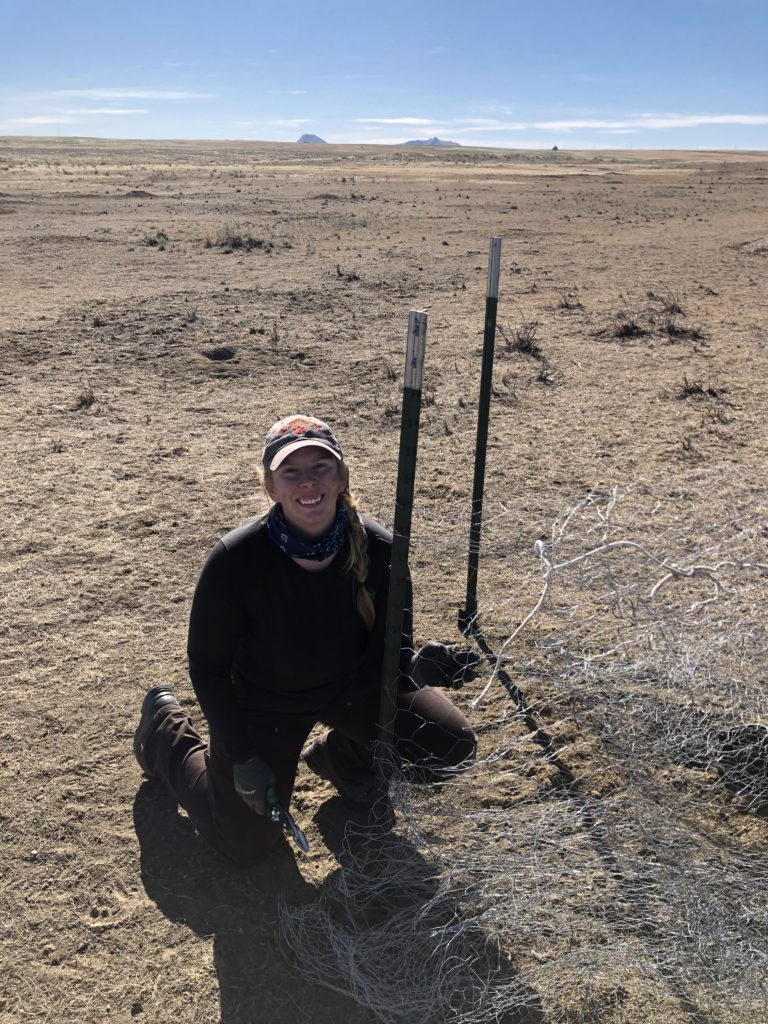

Nelson’s role is as a Ph.D. student and researcher, meaning she’s had the chance to do plenty of the on-the-ground work of trapping and moving foxes across state lines, but she said her true passion for the project lies in the research.

“We are basically using a couple main technologies to characterize this population as it is being reintroduced,” she said. “So, we’re looking at the short-term behavior of every single swift fox that’s moved and how that kind of scales up to their population growing, to their population becoming established and hopefully doing well from here forward.”

The information is gathered primarily through GPS collar data as the animals move and “non-invasively collected samples.”

“I’m picking up a lot of scat samples, and from that we’re getting as much information as we can — things like age, sex and which exact individual it was — so that’s really cool to tell us who’s moving where, who are they mating with and how is their population growing,” Nelson said. “And then we’re also looking at some cool technology to look at their diet and how that factors into the individual foxes picking the right habitat, selecting the right food and going on to hopefully be successful to have a lot of babies.”

Nelson’s work also continues Clemson’s swift fox research after Andrew Butler, a previous student of Jachowski’s, began on the project a few years earlier.

“The previous research was showing how limited swift fox were in the state, particularly this portion of Montana, and the project that Dana is part of is taking place in this gap in the swift fox range. So, Clemson, involved with many, many partners doing this, is helping put in that puzzle piece. It’s building on the research from before which was showing that swift foxes were having trouble connecting between those pieces and we need to actively put foxes in there to solve this problem,” said Jachowski, associate professor of wildlife ecology in Clemson’s department of forestry and environmental conservation.

In 1992, the USFWS received a petition to list the swift fox as an endangered species under the Endangered Species Act. These concerns prompted the 10 state wildlife agencies within the historic range of swift fox and interested cooperators to form the Swift Fox Conservation Team (SFCT) in 1994 and, in 1995, USFWS determined a threatened listing was “warranted but precluded by listing actions of higher priority.”

Through its partnering agencies and organizations, the SFCT continues to monitor and manage swift fox across their range to maintain the long-term population viability of this iconic prairie species.

“Swift fox, while being small and, as nocturnal animals, they’re not regularly seen my most people, they are abundant across the shortgrass prairie across eastern Colorado,” said Mark Vieira, carnivore and furbearer manager for Colorado Parks and Wildlife. “We have a very well-defined monitoring program that’s run at least over the last 20-plus years to make sure that we’re maintaining that level of occupancy for fox across their habitat types.”

And as she assists with rangewide expansion of swift fox and reoccupying traditional swift fox habitat, Nelson said the project is exactly the kind of experience she hoped for when she came to Clemson to pursue her doctorate.

“What I’m really excited about with this work is that I get to study a project that is actively working toward applied conservation goals. We’re really doing it. We’re bringing the species back, and I get to integrate that into my Clemson experience by sharpening my own skills and by improving my capacity for research and understanding — all while we’re doing good for the ecosystem,” she said.

After a semester on campus this spring, Nelson returned to Fort Belknap for the fall semester to collect samples, analyze data and continue to augment and build the swift fox population through 2024.

From Clemson’s standpoint, Jachowski said the work Nelson is doing has also helped create a new footprint for the university in the realm of ecosystem-level restoration by indigenous communities.

“Clemson is working on that landscape, but it’s in step with and following the leadership of the local indigenous community — and we’re just providing the technical skills,” he said. “And we’re learning a lot about these other cultural values that wildlife have that we often don’t think about. Here in South Carolina, we’re mostly private land and we tend to place more of a utilitarian value of wildlife for hunting or furtrapping or nuisance control. But there are important cultural values that can drive wildlife conservation and restoration that we’re also learning about through this project.”

Get in touch and we will connect you with the author or another expert.

Or email us at news@clemson.edu