CLEMSON – If you hear Adam Smith say something about a “bird brain,” don’t worry, he’s not degrading anyone. In fact, it’s a compliment of sorts.

Smith, a paleontologist and curator of the Clemson University Bob Campbell Geology Museum, is co-author of a study that shows how birds’ brains have changed over the millennia. Paleontologists study fossils to learn more about the history of the Earth. Smith said this study is a valuable tool to use for exploring the evolution of human intelligence.

“Studies of intelligence and cognition have been largely restricted to mammals,” Smith said. “But, more recently, scientists have discovered that some birds, particularly crows and parrots, have mental capacities that far exceed many types of mammals. I strongly believe that learning more about the ways avian and mammalian intelligence are alike, and different, is a valuable tool for exploring the evolution of human intelligence.”

The study itself

Birds are considered direct descendants of theropod dinosaurs. These dinosaurs moved around on two legs, had three-toed feet, a furcula (wishbone), air-filled bones, feathers, and laid eggs. Today, there are about 9,300 living species of birds.

The bird brain study samples three dinosaur groups – non-avian dinosaurs, archaic birds, and modern birds – to assess how brain size has changed over time. For their study, the researchers reconstructed the avian, or bird, brain’s evolution. They used a dataset of dinosaur brains that included information about extinct birds such as the Great Auk and Archaeopteryx, as well as living birds and even birds that didn’t fly. Some of these ancient birds would’ve been found during the Cretaceous Period when dinosaurs such as Tyrannosaurus rex and Triceratops roamed the Earth. The Cretaceous Period ended about 66 million years ago when a meteorite slammed into the planet, dooming non-avian dinosaurs and killing off a rather large group of archaic birds that do not have any descendants.

Birds that survived the meteorite-related catastrophe are believed to have been relatively small. Soon afterward, some lineages of modern birds expanded greatly in body size to fill roles left empty by the extinction of large non-avian dinosaurs. At the same time, other lineages of birds were miniaturizing to exploit other resources in their environment.

“Brain size, body size, and ecology are all interrelated in quite complex ways,” Smith said. “Conventional wisdom tells us that brain size and body size are relatively tightly linked. But, what we found was that brain size and body size were changing in much more complex ways than expected.”

Bird brains are remarkable

Corvids and parrots are two bird groups the team found to have a remarkable brain size. Corvids include birds like ravens, crows, and their close relatives. These bird groups have a remarkable cognitive capacity. They can learn and use language and tools, as well as remember human faces. Researchers say these birds’ brains evolved at a high rate to achieve these feats, as well as their sizeable brain-body size ratio.

“Fossils tell us that body sizes, skull sizes, and brain sizes have changed frequently throughout the evolution of birds,” Smith said. “Still, the complex relationship between these changes remains largely unexplored. We did find there are different ways birds achieve large brains and because larger brains typically correlate with increased intelligence, this study sheds some light on the beautiful complexity of evolution.”

The researchers say crows are the birds’ equivalent of hominins or human ancestors. The study shows crows evolved proportionally large brains by simultaneously increasing the sizes of their bodies and brains, with brain size increasing more rapidly.

“Anyone who has spent time around parrots and crows has seen for themselves just how smart these birds really are,” Smith said. “As a scientist who studies these fascinating creatures, it’s very satisfying to be able to find some hard data to back up what was already suspected, that being called bird-brained is actually quite a compliment. It’s also exciting to consider the complexity of potential paths to avian intelligence as this provides more questions and endless paths for future research.”

Joining Smith in this study are other paleontologists and evolutionary biologists from around the world. A report about the study, The Evolution of Large Bird Brains, can be found in the online version of Nature World News.

Anyone who wants to learn more about this study and others can visit Smith at Clemson’s Bob Campbell Geology Museum at 140 Discovery Lane Clemson, SC 29634-0174 when it reopens after the COVID-19 quarantine. Visit https://www.clemson.edu/public/geomuseum/ for information on when the museum will reopen.

“The museum does feature some fascinating exhibits that include all of the dinosaurian groups mentioned in this article – non-avian dinosaurs, archaic birds and modern birds,” Smith said. “There also is a very informative exhibit on hominid evolution that includes aspects of human cognitive development over time.

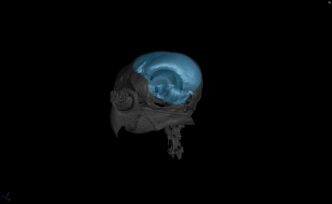

“We have plans to expand our exhibit on dinosaur evolution, which will include examples of brain endocasts, which is a 3D cast of a brain showing all of the folds and features. The expanded exhibit definitely will include some of the more exciting results from our recent study. We invite everyone to be on the lookout for our new exhibit and come visit the museum when we reopen.”

Until the museum reopens, Smith said there are great resources available on the museum’s website, including a virtual tour of the museum.

-END-