The gap between four generations collapsed February 23 in Tillman Hall auditorium as a member of the Greatest Generation took the stage before a crop of America’s latest generation of warfighters. World War II hero Capt. Dick Nelms, 99, traveled to Clemson from Mercer Island, Washington, to speak and answer questions from cadets in the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps program during a once-in-a-lifetime appearance that left everyone there in awe.

“Quite frankly, there are simply not enough men and women like him left among us,” said Army ROTC cadet commander Morgan Davis, a senior from Fairfax Station, Virginia, studying management who facilitated Nelm’s trip to Clemson. Davis noted that of the 16 million men and women who served in World War II, there now are fewer than 200,000 still living and they are passing at a rate of more than 7,000 each month, according to the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs.

“He represents a handful of those who were combat pilots who not only survived the war but continued to give back to their community and the next generations of leaders like those assembled here tonight,” said Davis. “Without heroes like him, it is quite possible that many of our grandparents and even our parents would not have had the same opportunities, because freedom is not free.”

Nelms was born on February 17, 1923, in Cleveland, Ohio, and grew up in Niagara Falls, New York. In 1938, Nelms moved to Columbia at age 15 after his father passed away. He and his older brother George became fascinated with Clemson University and dreamed of visiting the campus, but the war interrupted their plans. Eighty-four years later, Nelms finally fulfilled that dream.

“It’s great to be here finally. I’ve always rooted for Clemson —unless they were playing the University of Washington,” joked Nelms, who has lived on Mercer Island in Washington since 1953. “My brother and I liked USC too, but we called it the ‘University of Second Choice.’”

During their time in Columbia, Nelms and his brother collected stickers as a hobby and Nelm’s most prized sticker was a 1938 Clemson decal, which he gifted to Davis before making the trip to Clemson.

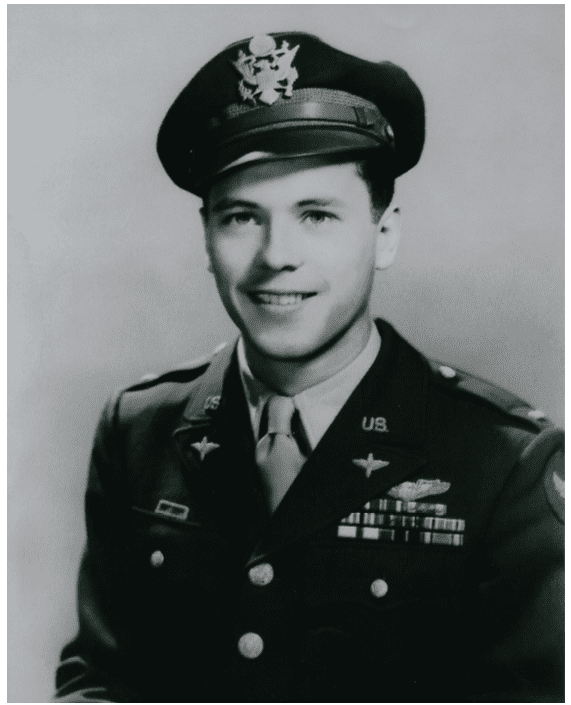

Nelms enlisted in the Army Air Forces (the direct predecessor of the U.S. Air Force) in 1942 and was accepted to Aviation Cadet and Pilot training for active duty in March 1943. After earning his wings in December 1943, he was assigned to the 447th Bomb Group, 8th Air Force, based in Rattlesden, England.

Nelms piloted the B-17 Flying Fortress, the iconic four-engine bomber that became a symbol of the United States’ airpower in the war. Nelms can still rattle off the specifications from the top of his head: “The B-17 was 75 feet long with a 104-foot wingspan and could carry more than 8,000 pounds of bombs, 13 50-caliber machine guns and 3,600 gallons of 100 octane fuel.”

Over the course of his service, Nelms flew 35 missions into Germany, France and other Nazi-occupied territories, sustaining battle damage in 25 of those missions. He also helped write and plan food and supply drops to the Marquis Freedom Fighters in France and others.

Nelms returned from his fourth mission, a 10-hour trip to Berlin, with more than 300 holes in his airplane, “Rowdy Rebel II.” The aircraft was repaired, but the drag created from all the eighth-inch thick patches slowed the plane so much that it could never fly in combat again. A large “WW” was painted on the tail for “war-weary” and it was used as a taxi for the rest of the war. Nelms and his crew were given a new plane, which they christened “Pandora’s Box” and completed an additional 31 missions.

The assembled ROTC cadets listened in silence as he described in detail what it was like to be on one of those missions, at the yoke of the aircraft and having to fly directly through the exploding shell barrages, unable to take evasive action as they were required to maintain their position in the formations. He recalled flying through the sudden bursts of smoke and then hearing flak tearing holes through the aluminum skin of the B-17. He said he had two things to handle at those times: The plane and fear.

“I tried to handle fear by concentrating on my training, keeping a soft hand on the controls and keeping my position in the formation … but fear wants to take over,” he recalled. “Your brain can become your enemy up there.”

Nelms explained how he would force himself to think positively to avoid the potentially paralyzing effects of fear. For example, he described an incident when an 88-millimeter shell from a German Flak cannon exploded 50 feet in front of his plane.

“I wanted to think, ‘If that had gone off a second later, we’d be on our way down!’” he said. “But I forced myself to think, ‘Isn’t it great it went off when it did? Everything is OK.’ Both are true statements. You pick the positive one. Thinking like that helped me.”

Nelms shared the story of another close call on a mission to bomb a Messerschmitt fighter plane assembly plant outside the town of Leipzig, Germany. The first volley of flak exploded directly underneath his plane, bouncing it through the air like a car hitting a speed bump, accompanied by the sickening sound of shrapnel tearing through the plane.

“It scared me. After about 10 or 15 seconds, I got ashamed of myself. You know, if you have a close call on a highway, you get scared, and then you might get a little angry, and it goes away. This did not go away,” he explained. “Then I got angry at myself for being scared.”

Moments later, a second volley came, exploding only 100 feet or so away. The explosion rocked the plane, pelting it with flak and bouncing off the bullet-proof windshield. Three pieces tore through the B-17’s nose, leaving large holes. Nelms leaned down and shouted through the holes, “You missed me!”

“I knew that shouting like that into my oxygen mask wasn’t going to shorten the war,” he laughed. “But you get tired of being a duck in a shooting gallery.”

Nelms spent more than an hour speaking to the cadets from the stage, standing behind the chair provided for him. Humor seemed to be a way he and his comrades handled stress. At one point, he had the whole room laughing with a story about how the charge of quarters (CQ) would rouse them from their sleep for missions, sometimes as early as 3 in the morning, by kicking open the door of their Quonset hut, turning on the lights and yelling “Up and at ‘em boys! Rise and shine! Off your back and out of the sack! Up up up!”

“One day, my bombardier threw his shoe at him,” recalled Nelms. “It went skidding across the floor. As the CQ walked out, he stopped and said, ‘I hope your accuracy improves somewhat later today.’”

Nelms earned numerous valor awards for his service, including the Distinguished Flying Cross, five Air Medals, the Presidential unit citation, and the Legion of Honour from France. After his speech, he took questions from the cadets, and one of them asked what advice he’d give to his younger self.

“Concentrate on your training. Practice it, ask questions about it. It may save your life someday. It did me.”

When asked what the secret is to a long life, Nelms quipped, “Stay alive.”

“I think it was Woody Allen who said, ‘I’m not worried about dying; I just don’t want to be there when it happens,’” he joked, then answered seriously. “I try to have a positive outlook. I was athletic in school – did three sports – and I’ve tried to keep things moving. I have an exercise routine that I do every day. All of that helps a lot.”

He concluded with a nod to his audience of soon-to-be Army and Air Force officers.

“People occasionally mention the Greatest Generation,” he told the cadets. “They worry about the young people today and say it seems like all they want is a cell phone and to take selfies and text each other. Well, I wish they were here with me today to see what I’m seeing: a room full of young men and women who have chosen a career that defends this country, that protects our freedom and keeps us safe. There is no greater reward than that.”