February 11 is celebrated globally as the International Day of Women and Girls in Science. To celebrate the day, we are highlighting five women with ties to the Clemson University College of Science who are making a difference with their work.

Dr. Katie Gray

Katie Gray knew she wanted to practice a broad scope of medicine and that she’d have to go somewhere rural to do so.

Few places are more rural than Kodiak, Alaska.

Gray is a family medicine doctor in Kodiak, the largest community on Kodiak Island on Alaska’s south coast. She works for the Kodiak Area Native Association, a nonprofit that provides health care and social services for Alaska Natives. Twice a month, she boards a small plane to visit KANA health clinics in Old Harbor and Karluk, small villages off the road system accessible only by air or by boat.

Gray’s interest in medicine started her senior year in high school after she shadowed an orthopedic surgeon in her hometown of Aiken, South Carolina. She graduated from Clemson University in 2013 with a degree in biochemistry before attending the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. While at Clemson, Gray worked in a lab at the Eukaryotic Pathogens Innovation Center (EPIC).

Doing a bit of everything

During medical school, Gray did a rotation with Dr. Oscar Lovelace, a Clemson alumnus and family medicine doctor in Prosperity, South Carolina.

“He’s a rural doctor who does a bit of everything, including delivering babies at his local hospital. I liked family medicine and how it engages with different age groups,” she said. “I wanted to find a residency program that allowed me to practice and learn a full scope of medicine.”

The Mountain Area Health Education Center in Asheville, North Carolina, was that place.

During her residency, Gray mentioned to the doctors that she wanted to practice the full spectrum of medicine in Alaska, a state she had fallen in love with during a couple of winter visits. A previous graduate worked in Kodiak, and Gray secured a four-week rotation at KANA. Her work there cemented her passion for community health.

Breadth of medicine

“I think it is challenging to feel comfortable practicing that breadth of medicine. There’s a wide variety of things you’re seeing, and you’re always learning something new,” she said.

Gray said learning about the culture of the patients she treats on the island helps her to better treat them.

“There’s truly an art to medicine. Something you read in a textbook doesn’t necessarily translate to the person in front of you because they come from their own specific background; they carry their own personal beliefs, values and experiences. It is an honor to be able to form relationships with my patients and learn about them so together, we can make treatment plans that incorporate what is important to them,” she said.

Renu Laskar

Renu Chakravarti Laskar owes her long and successful career as a mathematician to stubbornness.

The professor emerita of mathematics at Clemson University grew up in Bihar, India, when societal norms called for women to receive minimal academic training.

But that norm changed — at least for Laskar — after her mother, Devrani Chakravarti, who had never received a formal education, couldn’t read a telegram that announced a family member’s death. Her mother vowed to become educated — she later taught herself English and a couple of Indian languages — and insisted her daughters would, too.

“My mother wanted the girls in the family to be educated. She almost fought my father on this one,” Laskar said.

Not allowed to attend college

She received a high school education, but her father did not allow her to attend college. She was, however, allowed to study at home with tutors.

“The elders in my family felt it was inappropriate for a woman to become a mathematician. They said, ‘You are a woman. You should take domestic science,’” she said. “I am a very stubborn person. Since everyone discouraged me from studying math, I was determined to become a mathematician.”

Laskar took the exam to earn the four-year bachelor’s degree and received the highest score in the state of Bihar.

That led to a job offer at Ranchi Women’s College. Her roommate suggested she apply for a Fulbright Scholarship to earn her Ph.D. in mathematics at a U.S. university. She won the scholarship, and in 1958, left for the United States. She finished her doctorate at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign in 1962, becoming the first female Indian to earn a doctorate there – under the guidance of Roy Brahana. She then returned to India to marry her husband, Amulya Lal Laskar, whom she met in Illinois.

A series of firsts

Renu became the first female faculty member at the Indian Institute of Technology in Kharagpur, in 1962.

“I was happy to be the first and to set an example for those who would come after me — colleagues, students and family,” she said.

After three years at IIT and another three at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, Laskar came to Clemson with her husband, a renowned physics professor. She served as a faculty member for 38 years.

While she was at UNC, Chapel Hill, Laskar met — and eventually conducted research with — Raj Chandra Bose, a mathematician best known for his work in design theory, finite geometry and the theory of error-correcting codes. He introduced her to Paul Erdos, one of the most prolific mathematicians of the 20th century, with whom she collaborated many times.

“I worked with some of the 20th century’s greatest mathematicians, and they were friends of mine. We worked together, and they stayed at our house with my family. They enjoyed my math and my cooking,” she said.

“I loved my subject. I loved teaching,” she added. Laskar said that she loved the students and the opportunity to do research and collaborate.

“I am so appreciative of Clemson for all the opportunities it afforded me.”

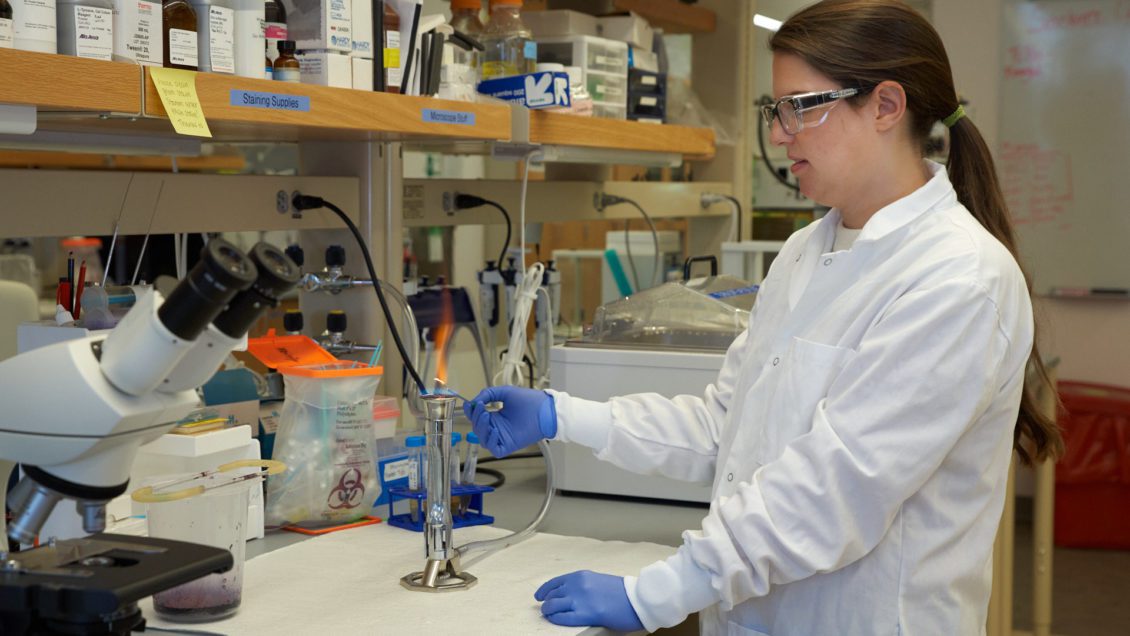

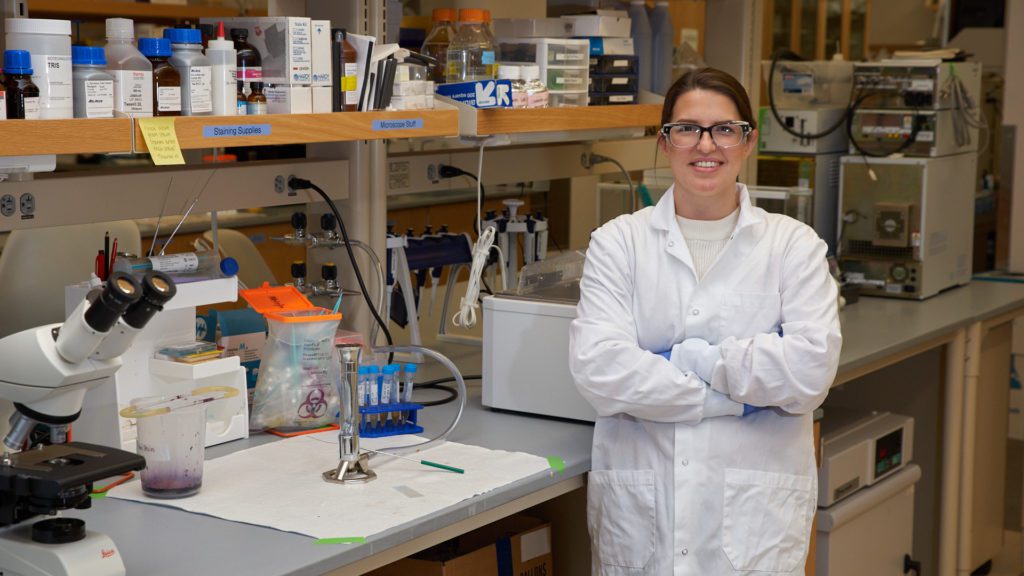

Sophie Millard

Growing up, Sophie Millard wanted to be a doctor.

When it was time for her to go to college, she decided to become a nurse instead and enrolled in Clemson University’s nursing school.

But while taking a microbiology course, Millard realized she wasn’t interested in treating diseases. Instead, she wanted to learn about what caused diseases.

“When I took that microbiology course, I fell in love with it. I realized that there are microbes that are not pathogens but that are beneficial. The field was emerging at the time, and I thought it was interesting that they contributed to health,” she said. “We’re realizing that gut microbiomes are important in many aspects of human health, from developing the immune system to whether or not you get diabetes. Disease resistance is often correlated with your gut microbiome.”

Change in plans

After spending two years in nursing school and a year off to get married and have her son, Millard returned to Clemson, changing her major to biological sciences and minoring in microbiology. She took as many microbiology courses as she could.

She graduated in 2019. Around that time, she heard the Department of Biological Sciences was interviewing Anna Seekatz, who researches gut microbiota, for an assistant professor position. She contacted Seekatz, who was in Michigan at the time, to see if she could work with her.

“Our interests really lined up,” said Millard, who began her Ph.D. program studying under Seekatz in August 2019.

The gut microbiome is a highly diverse microbial community. When it is damaged, such as following antibiotic treatment, it can become susceptible to different pathogens that cause disease. Millard’s research focuses on the pathogen Clostridium difficile, a bacteria that can cause an infection of the large intestine that can be life-threatening for the immunocompromised, hospitalized or elderly.

“Your gut microbiome is important, so we need to learn how to respect and restore them,” she said.

Fueling curiosity

Millard credited her father, a horticulture professor in the Clemson Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences, for fueling her curiosity about science. But there was a time that she didn’t think she’d pursue a Ph.D. or do research in a lab.

And while she doesn’t want to go into academia like her father, she does want to do research after she earns her Ph.D., likely in 2024, perhaps in the pharmaceutical technology industry.

“I want to go into something where we can figure out how to modulate or improve the gut microbiome,” she said. “I want to do something that improves people’s health. It just won’t be as a medical doctor.”

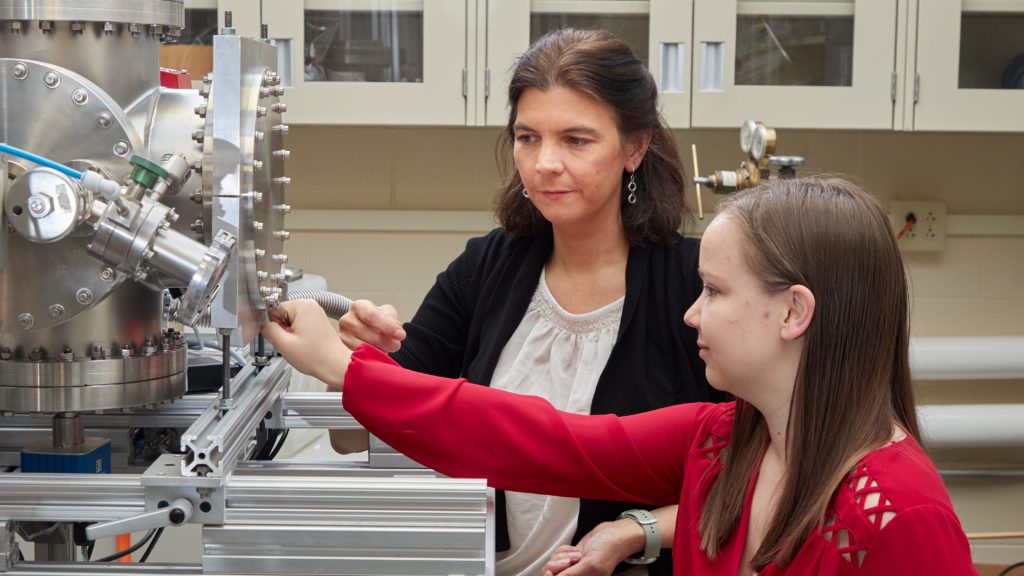

Joan Marler

Joan Marler loved math growing up and likely would have been happy majoring in the subject in college.

But after heeding her mother’s advice to explore subjects with a math foundation during her first semester as a first-year student at Wellesley College, Marler pursued a career in physics.

“At some point, math becomes more abstract if you want to pursue that postgraduate. In physics, it becomes more applied, and I liked that,” said Marler, an associate professor in the Clemson Department of Physics and Astronomy.

As an undergraduate, she had opportunities to tutor other students. Besides her interest in teaching physics, Marler also discovered particle physics, the branch of physics that studies the elementary building blocks of matter, radiation and their interaction. She spent one summer at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, which operates the largest particle physics laboratory in the world.

Small world

“I was hoping to be on one of the big ring collider experiments. But instead, I was assigned to the antihydrogen experiment. So, I thought I would be assigned to a project accelerating particles to capital M, mega, electron volt energies. But instead, we were trying to cool atoms to little m, millielectron volt energies to form antihydrogen atoms. So I was about nine orders of magnitude off!” she said.

But it was there that she was exposed to the experimental tools of charged particle trapping that she still uses in her research today.

Marler completed her Ph.D. in physics at the University of California San Diego with a research project studying the low-energy interactions of antimatter with ordinary matter.

After a postdoctoral fellowship at Lawrence University, where she taught and conducted research, and postdoctoral research positions at the University of Aarhus in Denmark and Northwestern University in Chicago, Marler joined the Clemson faculty in 2013.

Here on earth

Her research involves laboratory astrophysics.

“You can’t travel light-years and do experiments there,” she said. What she and other physicists can do, however, is study highly charged ions here on Earth to understand what’s happening in the universe billions of light-years away. One project she’s working on involves spectroscopy on multi-charged gold and other elements near it on the periodic table and then looking for those signatures near explosive events in the universe, such as neutron star mergers.

Marler recognizes her start in physics wasn’t the typical female undergrad experience. As an undergraduate at a women’s college, her physics classmates were all women — which is not the case at most schools. In 2020, women earned only 25% of physics bachelor’s degrees awarded in the U.S. — the highest percentage ever recorded, according to the American Physical Society. Marler is an advocate for women in science in general — and physics in particular — and is planning a conference for undergraduate women in physics to be held in Clemson in 2024.

“It feels really different at this point in my life to go to a meeting that’s all female,” she said.

Kaylan Jackson

With a heart to help others and a love for science, Kaylan Jackson thought the medical field would be a logical career path.

But any thought she had of becoming a medical doctor was eliminated during one of her high school internships when she discovered she was faint at the sight of blood.

“Really, I found that I was drawn to the ‘how’ behind the instruments doctors used and was fascinated by the hidden heroes — the scientists, that created life-saving medications and diagnostic tools,” Jackson said. “Eventually, this led me to a career in analytical chemistry and method development.”

Jackson earned her undergraduate degree from Gardner-Webb University before enrolling at Clemson as a Ph.D. student in the Department of Chemistry.

Lab work

While at Clemson, Jackson spent one year as a clinical research scientist in the Clemson University Research and Education in Disease Diagnosis and Intervention (REDDI) lab. Delphine Dean, the Ron and Jane Lindsay Family Innovation Professor of Bioengineering, founded the lab in 2020 to provide regular, rapid COVID-19 testing of Clemson faculty, staff and students.

Jackson’s Ph.D. research involved the isolation and characterization of exosomes — lipid-based bionanoparticles found in bodily fluids — that have shown much promise in the development of an early screening “liquid biopsy” for ovarian cancer, which is the fifth-leading cause of cancer deaths among women.

Scientists traditionally regarded exosomes as ”trash” from cells. But researchers say they could be the key to detecting many cancers in their early stages. Jackson developed a technique to isolate the exosomes quickly that requires no specialized training or lab equipment.

Dream job

“When I started thinking about what I wanted to do after graduation, I decided I wanted to go into biotherapeutics, and my dream job would be at Johnson & Johnson,” she said. “So, I decided to see if I was good enough to get an interview.”

She was.

Jackson now works as a scientific consultant in the company’s cell and gene therapy division.

As a consultant, Jackson develops protocols and ensures the methods are sound.

“You could say I’m one of the brains behind the hands,” she said. “As a consultant, I don’t physically see the experiments being run or the process in person. But I believe my time in the REDDI lab at Clemson, where I took part in the clinical experiments and had my hands on the patient sample processing, gave me an advantage because I know how a clinical lab works and what a scientist needs.”

The projects she’s working on now include a number of impactful drug and gene therapies.

The College of Science pursues excellence in scientific discovery, learning, and engagement that is both locally relevant and globally impactful. The life, physical and mathematical sciences converge to tackle some of tomorrow’s scientific challenges, and our faculty are preparing the next generation of leading scientists. The College of Science offers high-impact transformational experiences such as research, internships and study abroad to help prepare our graduates for top industries, graduate programs and health professions. clemson.edu/science

Get in touch and we will connect you with the author or another expert.

Or email us at news@clemson.edu