February 11 is celebrated globally as International Day of Women and Girls in Science. The United Nations General Assembly established the day in 2015 as a way to encourage women and girls’ full and equal access to and participation in science. To celebrate the day, we are highlighting five women who have ties to Clemson University’s College of Science.

Dr. Shannelle Campbell, surgeon

For Dr. Shannelle Campbell, medicine was a natural career path.

A high school Advanced Placement biology class initially sparked her interest in becoming a physician.

“I was fascinated by how the human body worked in all of its intricate and cohesive complexities,” she said.

She knew she also enjoyed listening to people’s stories and figuring out ways to help them through their most challenging struggles.

“The physician’s role as a healer resonated with me,” said Campbell, who is now an assistant professor in the Department of Surgery at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

While attending Clemson University to earn a bachelor’s degree in biochemistry, she volunteered at free clinics in Columbia, her hometown, and Seneca, South Carolina.

“I enjoyed interacting with patients; it’s deeply gratifying when you’re seeing people who need help, and you have a solution. There are so many things in life that you can’t fix for people. But there are times, in medicine, when there’s a defined issue that you can do something about,” Dr. Campbell said. “That was powerful for me, and it only strengthened my resolve to go into medicine, although I didn’t know what kind of doctor I would become.”

One of her first rotations as a third-year medical student at Yale was in pediatric surgery — and this is when she decided surgery would be her field.

“I was in awe of the pediatric surgeon whom I worked with the most. I loved how she approached problem-solving in such a focused, sure way, and I loved that a surgeon could be facile in the treatment and understanding of both surgical and medical problems,” she said.

After she finished her residency at UNC, Dr. Campbell returned to South Carolina to go into private practice in Spartanburg.

“As a resident, you learn how to do surgery. Spartanburg put the finishing touches on my education, because there’s so much nuance in the doctor-patient relationship, your relationship with colleagues, how you function as a doctor in the community that you don’t learn in school or in training,” she said.

After more than eight years in private practice, Dr. Campbell returned to UNC as a faculty member.

“Being a surgeon is a tremendous honor. I am very thankful to be a part of patients’ lives and to help them however I can,” she said.

Yara Luis-Stoll, Head of Product

Yara Luis-Stoll can point to somebody who saw potential in her at each step of her career.

Now, she works to do the same for other women as head of product for Latinas in Tech, a nonprofit organization that provides the resources, opportunity and community Latinas need to thrive, innovate and lead in tech.

My story is the perfect example of why it’s so important that people who are in positions of power look out for high-potential folks from underrepresented groups,” said Luis-Stoll, a first-generation college student who graduated from Clemson in 2008 with a master’s degree in mathematical sciences with a focus on operations research.

Luis-Stoll originally wanted to be an attorney but was advised to major in accounting in high school because she was good at math. She quickly knew accounting wasn’t the career for her. Fortunately, one of her undergraduate math professors at the Unisersidad de Puerto Rico suggested joining the school’s computational mathematics program.

Perfect fit

“The program was a perfect fit for my analytical mind,” she said. “I’m grateful that she saw the potential in me, not just seeing it, but acting on it.”

Luis-Stoll came to Clemson for her master’s degree, where her focus was operations research. She worked at US Airways for six years, some of which she spent trying to improve the international recheck process at various airports.

Later in her career, she interviewed for a data science position supporting the marketing division at GoDaddy. Instead, she was hired as a director to lead data-driven strategy in the division.

Now she works to provide other women the same opportunities as were afforded to her through Latinas in Tech, which connects, supports and empowers Latina women through learning opportunities, mentorship and recruitment.

“To me, it’s like solving a puzzle,” Luis-Stoll said. “There have been plenty of times in my career when I wasn’t the one building the mathematical model, but I asked the right questions thanks to my curiosity and analytical mind. These attributes allowed me to discover a new segment of customers that should be served in a different way. Having that strong math foundation and that way of thinking can add value to any organization.”

Priyanka Bhattacharya, Tesla researcher

Priyanka Bhattacharya, a senior cell research engineer at Tesla Motors, the American electric vehicle company, never expected to work in the automotive industry.

As a doctoral student in Clemson’s Department of Physics and Astronomy, Bhattacharya conducted seminal research that showed for the first time the negative impact of plastic nanoparticles on photosynthesis in aquatic organisms, pioneering a new area of research on plastic pollution in marine environments.

She devised new methodologies to detect harmful metals in wastewater and remove oil from water using novel hyperbranched macromolecular architectures and dendrimers.

She received a Linus Pauling Distinguished Postdoctoral Fellowship at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) with a research proposal to investigate using the same type of polymers for remediating nuclear waste at the Hanford Nuclear Site. That site, in Washington state, produced plutonium for America’s nuclear arsenal and is considered by some experts to be “the most toxic place in America.”

Energy storage

However, once she got there, the energy and environment division director asked if she’d be interested in working on energy storage and batteries instead. She said yes. During her three years there, she explored dendritic polymer architecture in energy storage to improve the performance of Li-air and Li-sulfur batteries.

“These polymers are multi-functional, and I was able to use the same polymers to improve energy storage devices,” said Bhattacharya, whose interest in physics was sparked in high school by conversations she had with a family friend who was a senior researcher at a government institute in India.

Her research at PNNL caught Tesla’s attention.

“They came across some of my papers and were interested in that technology,” she said. “Irrespective of one’s academic background, Tesla is keen on hiring people based on their Tesla experience, knowledge and motivation to drive the world to a sustainable future.”

Now, Bhattacharya works in Tesla’s active materials research group, working to find the next generation of active materials that will power electric vehicle batteries in the future.

“Tesla’s over-arching goal is to make electric vehicles and energy products a mass-market product base so that everybody can start switching from gasoline vehicles,” she said. “We, as a team, are working on the next generation of batteries that will have increased range and faster-charging capabilities at a lower cost.”

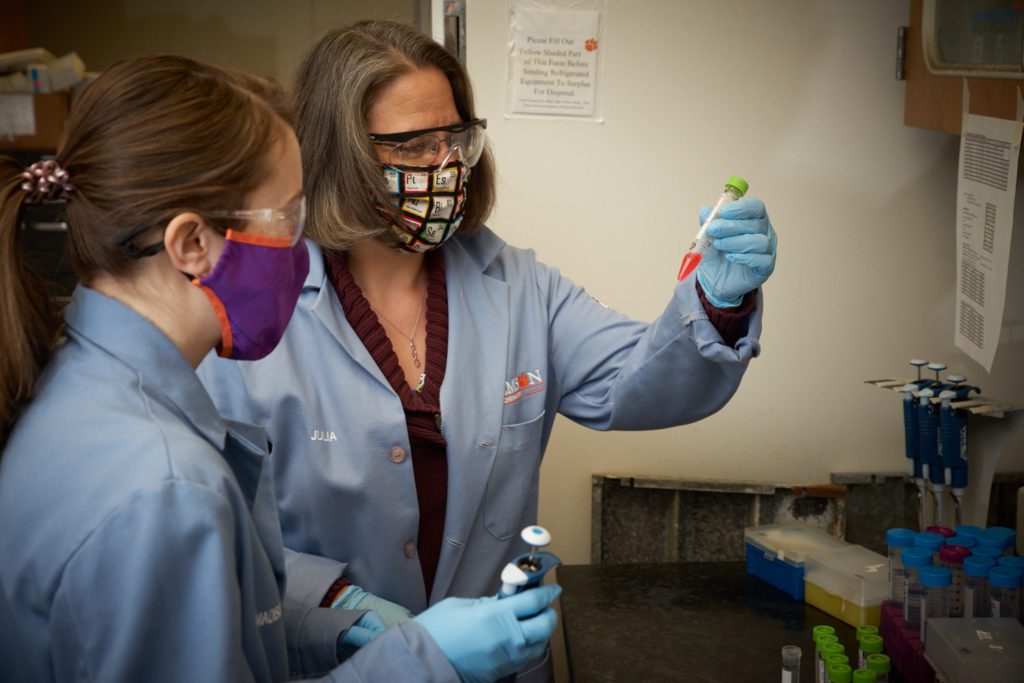

Julia Brumaghim, chemistry professor

By the time she was 12, Julia Brumaghim knew she wanted to be a university professor.

“I had it all laid out. I was going to finish high school, go to college, then go to graduate school, do a postdoc and then I was going to get a faculty position,” she said. “I just didn’t know in what yet.”

As a child, Brumaghim, a self-described gigantic nerd, had always been interested in science-y things. For her first 4-H poster contest, her topic was genetically engineering tomato plants to glow. The following year, her poster was about nuclear reactor design.

“I was next to posters on how to take care of your hedgehog,” she said.

She figured out the “what” when she took a high school chemistry class and fell in love with orbitals, which are the areas within atoms where there is a high probability of finding electrons. The arrangement of electrons in an atom dictates how atoms interact. She worked at a national lab, the Laboratory for Laser Energetics, in high school, where she synthesized liquid crystals.

“Chemists are really great at making molecules. They make drugs and new materials. You can invent things from the ground up, like molecular Tinkertoys,” she said.

Doing research was appealing because she wanted to ask questions, find the answers and make discoveries. But she wanted to teach as well.

“I wasn’t willing to give up one for the other,” said Brumaghim, a bioinorganic chemistry professor at Clemson.

Oxidative stress on cells

Today, Brumaghim’s research focuses on DNA and oxidative stress on cells, which is an underlying cause of many diseases of aging, including neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, cardiovascular disease and cancer, and how antioxidants can prevent metal-mediated oxidative damage.

“We’re trying to understand the underlying causes of the damage, and we’re trying to understand the basic properties of how and why these antioxidants work, the chemistry of it,” she said.

Her lab is also doing research connected to nuclear waste remediation, circling back to one of Brumaghim’s interests when she formulated her career plan.

“I actually ended up doing two postdocs instead of one, but otherwise, my plan worked out. It had to. There was no Plan B,” the professor said, acknowledging the unusual clarity in her career plans at an early age.

Lorena Endara, herbarium curator

Lorena Endara’s love for botany and science started early thanks to her family’s love of plants and to her father, who worked as an engineer at NASA’s satellite tracking station in Ecuador while she was growing up.

“My brother and I admired the science that enabled space travel. We loved to see the computers inside the station and the huge antenna that was in the middle of the highlands, which is my favorite ecosystem in Ecuador,” said Endara, who is the curator at Clemson University’s herbarium and a lecturer in the Department of Biological Sciences.

Her father introduced astronauts who visited the station to his children, and Endara still has vivid memories of meeting Kathryn D. Sullivan, the first American woman to walk in space.

“I remember her blue uniform, her embroidered NASA logo and the American flag. She was the tallest woman I had ever met to that day. I remember the big boots the astronauts were wearing, too,” she said. “I am sure that the exposure to science and women like Kathryn Sullivan inspired my career.”

Fell in love with science

Her father’s love of travel and a supportive family empowered Endara to pursue her interest in orchids and explore Ecuador’s diverse ecosystems and remote forests.

Endara, who holds a Ph.D. from the University of Florida, credits her decision to pursue a career in botany to two professors she had as an undergraduate at the Catholic University of Ecuador.

“They were the ones that made me fully fall in love with science and make plants my career,” she said.

Now, she curates Clemson’s herbarium, which houses a collection of about 100,000 documented, dried and pressed plant specimens that can be used for a wide variety of plant research.

“Herbaria are essentially time capsules and a lot more dynamic that just specimens in a closet. These historical collections teach us about nature and how it is changing, but they are also a valuable repository of DNA resources,” said Endara, who wants to expand the herbarium’s collection and increase botanical awareness in the community.

Get in touch and we will connect you with the author or another expert.

Or email us at news@clemson.edu