Whether you are aware of it or not, you likely have been affected by what are known as “forever chemicals.”

Forever chemicals are industrial chemicals that do not naturally break down in the environment. Instead, they build up and can take up to hundreds of years to decompose. They are used in many things, from non-stick kitchenware and takeout containers to firefighting foams and stain-resistant upholstery.

The main chemicals at play here are perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) found in the class of substances called per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). PFAS utilize fluorines, elements from the halogen family that includes chlorine, which is part of the reason why they are so harmful and difficult to breakdown.

The problems occur at the cellular level. Cellular respiration is the metabolic process that creates adenosine triphosphate, or ATP, the source of energy for cells. Forever chemicals replace hydrogen with fluorine and in turn the carbon molecules cannot be broken down in this process. The problem is that these elements are not interchangeable. Hydrogen is the smallest element and can pass through cell transporters and be broken down. Fluorine cannot, and instead it blocks or confuses receptors and enzymes.

Physical effects

Over time, this causes problems for the human body. These chemicals inhibit aerobic processes and make it harder to lose weight because the body cannot use its energy from ATP efficiently. Fat does not break down because of this lack of energy, and those trying to lose weight may find they are more easily exhausted from aerobic exercise.

“We are only now beginning to really see and understand the effects these chemicals are having on humans,” said Clemson professor of biological sciences William Baldwin. “But it appears these chemicals are associated with childhood and even adult obesity.”

Lanie Williams, a master’s student in Baldwin’s lab, said, “PFOS exposure is of particular concern here in the United States where many of us consume a high-fat diet. Coupling PFOS exposure with an influx of fats from our diet can worsen some of the negative effects that we are seeing, such as lipid buildup in the liver.”

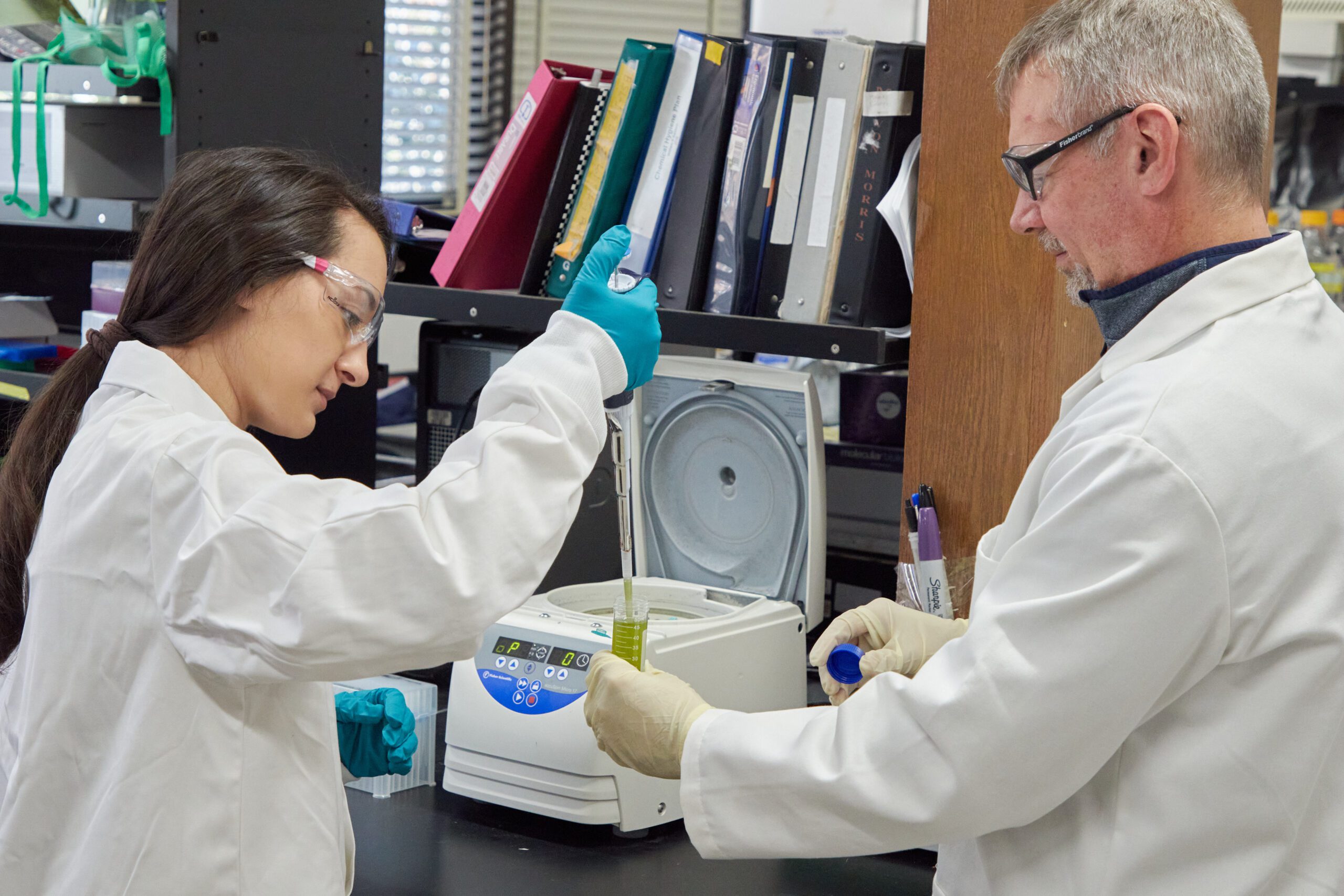

Baldwin’s research — which used mice as test subjects to study the processing of forever chemicals — supports this in the findings.

“We saw that PFOS causes inflammation, which is one of the mechanisms by which we get increased obesity,” he said. “We were also able to see that the uptake of PFOS is very similar to the uptake of fats in the body. PFOS is likely moving through the same transporters that would intake other organic anions such as fatty acids.”

Confusion

This could explain why cellular systems confuse the elements of forever chemicals for the elements like hydrogen that are usually involved in bodily processes.

Baldwin’s lab is now investigating the direct effects of PFOS and other PFAS on mitochondrial function in muscle to determine if and how they alter fatty acid metabolism and ATP production in our muscles as well as our livers.

But if forever chemicals are causing so much damage to the environment and to us, why keep using them? Baldwin said it’s because they are cheap to produce and practical to use.

“We don’t do a good job of talking about the plusses and minuses of industrial chemicals in the United States,” he said. “Things don’t get regulated enough here because what may be toxic is also cost efficient and doesn’t always have an alternative that is as effective yet.”

However, alternatives are being developed and scientists are working to decrease the repercussions felt by humans and the environment.

Certain chemicals have already been taken off the market or are in the process of being removed from the market, and the results are already starting to make a difference.

“I think these small changes, and even just taking one forever chemical off the market, will without a doubt have a positive impact,” says Baldwin.

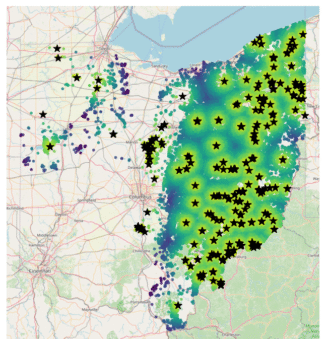

PFOS was taken off the market in the early 2000s, and populations that were previously exposed to it have shown they now have less than half the PFOS in their systems as they once did.

The Baldwin lab’s research will be featured in the journal Toxics in a special issue on PFAS toxicity and metabolism. Baldwin and Subham Dasgupta, a Clemson Department of Biological Sciences faculty member, are two of the editors of the special issue.