Stephen Parker ’11 is an architect, but to find out what he’s passionate about, don’t ask about towering bridges or sprawling cityscapes. Ask about a door in a mental health facility.

“There are a lot of things that go into just the function of a door — respect, privacy, dignity — and give you a sense of control over what social interactions you want to have, or that you are forced to have,” he explains.

Parker is a certain kind of architect, a Behavioral Health Planner, who focuses on designing healthcare facilities that see people at their most vulnerable. His attention to detail is a reflection of his education at Clemson and experience as a design professional. But most of all, it’s personal.

I often tell students passion is a great place to start. But what motivates you? Passion burns bright, but it can burn you out

Supporting veterans

Parker says his path to his career started at birth, and the emotional resonance grew over time. His namesake was a family member who died of a drug overdose. His godfather was a veteran, and several members of his extended family struggled with addiction and mental health challenges.

While life experiences gave him insight into how mental health impacts families, his education at Clemson began to reveal how the built environment shapes the people in it.

As an active member of the Clemson chapter of AIAS (American Institute of Architecture Students), he not only led discussions about wellness in the studio culture but also gave input into the design of Lee Hall III, which was constructed while he was in school.

“It was a pivotal time to be a student,” he recalled.

As he was beginning to pursue his Master of Architecture at the University of Maryland, many of his childhood friends were returning from Iraq and Afghanistan.

“Seeing my buddies returning from serving in uniform abroad — many with stories of combat trauma, PTSD and traumatic brain injuries — gave purpose to my graduate design work,” he explained. “Addressing gaps in the Military Health System for them and their families helped give purpose to my design and advocacy.”

After earning his architectural license, Parker became part of a team that developed the new Inpatient Mental Health Design Guide for the VA, influencing the design of the facilities serving more mental health patients than any other system in America. He was elected to the AIA Strategic Council, where he championed the Mental Health + Architecture Incubator.

“During December 2019, that was a topic not many were interested in addressing, but that changed substantially in spring of 2020, with the pandemic acting as a catalyst for my advocacy efforts,” he explained. As more of the world was stuck inside, more people became aware of how their indoor environments impacted their mental health.

Close to home

Then in 2023, something happened that transformed Parker’s perspective in an even deeper way: the same week his first child was born, one of his parents was admitted to a psychiatric facility.

A person who he had loved and known his entire life became unrecognizable from memory loss and delusional paranoia. Visits were limited to 15 minutes, during which he would try to get updates from his loved one, who had become an unreliable narrator.

“Not being able to remember taking medications is a big issue when your other diagnosis is delusional paranoia, and people forcing you to take pills is not helpful when they’re telling you, ‘It’s good for you.’ You don’t believe them because you see fictions that aren’t there,” he explained. “So many families are going through similar experiences in their own unique ways.”

He also saw with his own family what he had learned through research: the tiniest details of a facility’s design can help or hinder someone in distress.

Details like doors.

Designing for recovery

“Many times, the door is the hardest thing to design for,” Parker explains. He noted that when patients are checked in to mental health facilities, their clothing and possessions are often taken from them.

“If you’re an individual who is very paranoid, your possessions, you might have a lot of anxiety about not knowing where they are or are they safe.”

But even once possessions are returned, patients are housed in rooms they can’t lock themselves. And the doors are opened constantly — at all hours — by staff checking on the patient’s condition. The lock clicks, door opens, light spills in from the hallway, and the patient’s sleep is disrupted.

“That might be very triggering for someone with certain conditions or traumas,” he pointed out. This is the kind of problem for which he has a design solution.

“You put in a window with blinds that can be controlled from the inside and outside so the provider can look in discreetly,” he said, “and the patient can also choose whether to look out or not.” He added that giving patients an occupancy lock while staff have an override key is another measure that helps give people a sense of control and safety. Nightlights give patients autonomy over when to fall asleep.

“If you give them choices, if you give them a voice in their treatments, then they are better able to get on the road to recovery because they feel like they can grasp what’s happening to them and they’re not simply receiving care passively — they are a partner in their care.”

Every element of the treatment facility has a purpose. “You don’t want to give a patient anything to distract them from the key goal: their recovery.”

From passion to purpose

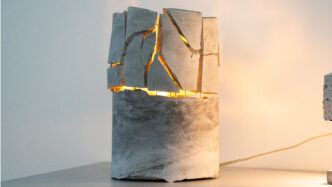

Renderings of Parker’s projects include the Aqqusariaq Recovery Centre in Iqaluit, Nunavut, Canada (top), the Southeast Psychiatric Treatment Center at Norristown State Hospital (bottom left), and the Emergency Behavioral Health Crisis Walk-in Center in Dauphin County, PA.

While Parker has experience with designing facilities for worst-case mental health scenarios, his projects incorporate wellness into the design for many types of clients around the world. Currently, he leads the Mental+Behavioral Health projects around the world at Stantec and is an Associate to the Board for the UK-based Design in Mental Health Network.

He has been part of the planning team for the Cleveland Clinic’s new 1 million square foot Neurological Institute, a community hospital in Kenya, sensory spaces for students, mental health units for Canada’s largest hospital, a recovery center in a remote Indigenous community near the Arctic Circle, and many more.

His work has earned him multiple awards, including the AIA Young Architects Award. He is also an active Clemson alumnus, frequently engaging with the Master of Architecture + Health program to advise on research and mentorship to students.

“I often tell students passion is a great place to start. But what motivates you? Passion burns bright, but it can burn you out.

“Purpose can sustain you.”