For years, astrophysicists have been searching for binary supermassive black holes at the center of galaxies.

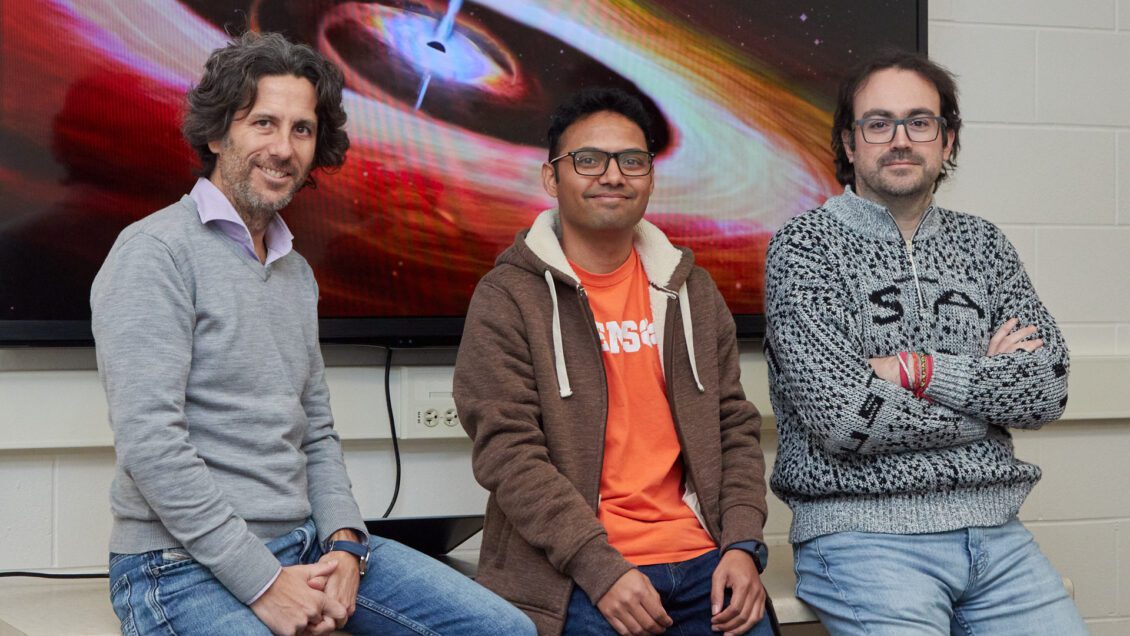

After analyzing more than 100 years of data, Clemson University astrophysicists may have found such a system.

All galaxies at some point have merged with another galaxy, and every galaxy has a supermassive black hole at its center, containing between 100,000 and tens of billions times more mass than our sun, said Sagar Adhikari, a Ph.D. student in the Department of Physics and Astronomy.

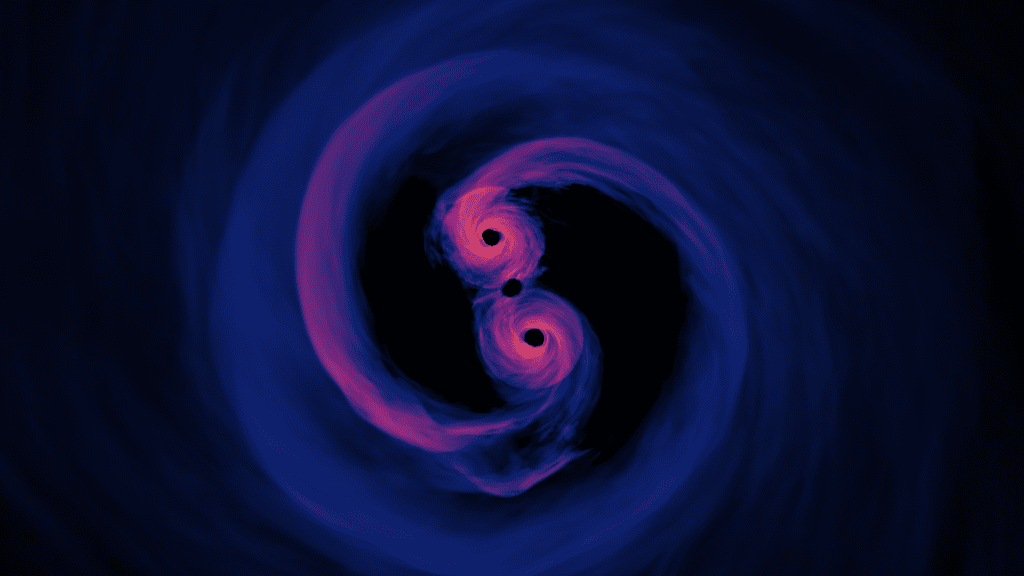

Some of these supermassive black holes form a pair, and when they do, they emit gravitational waves. Gravitational waves are of great interest to astrophysicists, but today’s ground-based detectors aren’t sensitive to the gravitational waves emitted by binary supermassive black holes.

Looking for signs

While waiting for space-based gravitational wave observatories to go online, astrophysicists are looking at other signs that a galaxy could host a binary supermassive black hole system, said Pablo Penil del Campo, a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Physics and Astronomy.

One sign is a repeated light emission from a gamma-ray blazar, a type of galaxy powered by supermassive black holes. Blazars appear bright in all forms of light, including gamma rays, the highest energy light, when one of the jets of matter happens to point almost directly toward Earth.

“It’s like a lighthouse,” said Marco Ajello, associate professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy.

Blazars display variable emission across the entire electromagnetic spectrum, with timescales that can range from a few minutes to several years.

Exhibiting evidence

Penil and his collaborators studied five blazars. He found that PG 1553+113, which Penil described as the most well-known blazar in the context of periodicity behavior, exhibited evidence of a 2.2 quasi-periodic oscillation in radio, optical, ultraviolet (UV) and gamma-ray bands.

In addition, while observing the multiwavelength bands, the researchers observed an increase in the flux (trend) in PG 1553 +113 in the gamma-ray, x-ray, UV, optical and radio bands.

“This was the first time that this property of long-term trend was observed in this blazar,” Penil said.

The question was whether the 15-year-long trend was part of a longer period or only a transitory phenomenon.

“If the trend was part of a longer period, then we could potentially explain that with the binary massive black hole system,” said Adhikari.

Archival data

The researchers combed through archival data from several optical telescopes to determine whether the trend was part of a longer period. They found observations dating back to the 1920s. They found another period which corresponds to the blazar, this one 22 years in length, the first time a secondary long period of this blazar was detected.

Based on their findings, the researchers predict that the peak of the emission associated with this period will likely be observed in July 2025.

“We’re excited to discover the second period that is expected if you have these two supermassive black holes orbiting around each other. They basically create this over-density of material which orbits around the system with a timescale that is typically five to 10 times longer than the orbit of the pair. That’s what we found,” said Ryan Westernacher-Schneider, a former postdoctoral fellow at Clemson.

Detailed findings can be found in the paper titled “Multiwavelength analysis of Fermi-LAT blazars with high-significance periodicity: detection of a long-term rising emission in PG 1553+113” published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society and in the paper titled “Constraining the PG 1553+113 binary hypothesis: interpreting a new 22-year period” published in the journal Astrophysics.

Get in touch and we will connect you with the author or another expert.

Or email us at news@clemson.edu