An orange wheel rolls across the concrete until it suddenly leaps as if it has a mind of its own.

Another robot undulates like a fish beneath the surface of an indoor pool, while a third robot twirls as it slides through pipes.

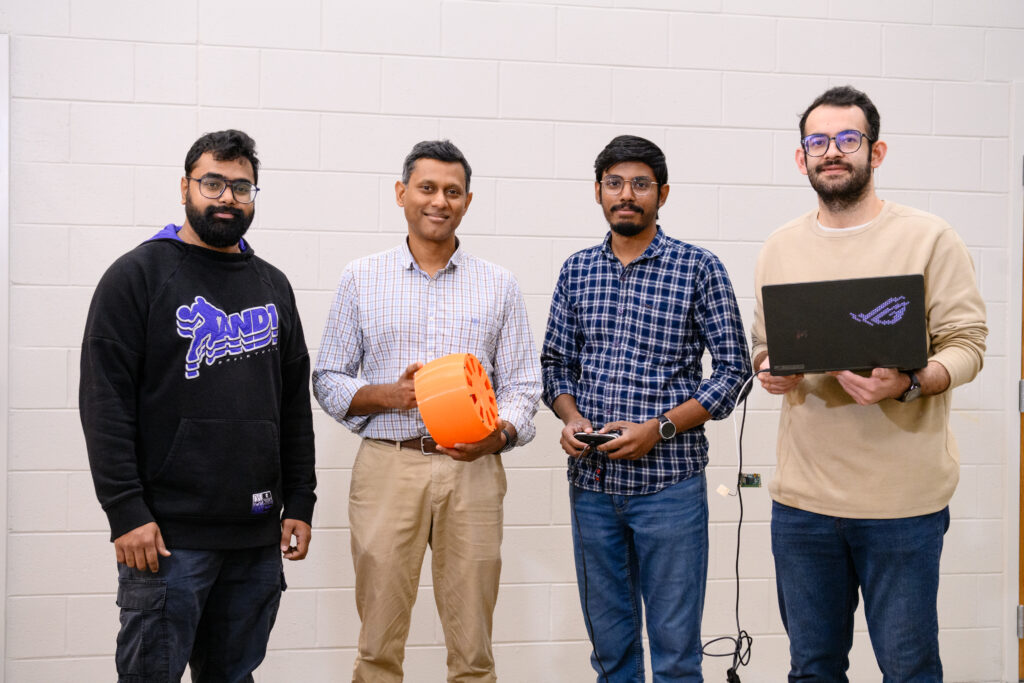

Now that they have created robots that can jump, swim and crawl, Phanindra Tallapragada and his team at Clemson University are looking to go higher– literally.

Tallapragada, a professor of mechanical engineering, has launched a new project that could lead to robots that fly like insects.

For Tallapragada, lifelike robots are a piece of a larger puzzle. They are the physical embodiment of the math that drives their movements.

“A lot of robotics today is perceived as designing something with motors, microcontrollers, machine learning and AI– and less importance is given to the dynamics and math, at least in the public perception,” Tallapragada said.

“I want to change that a little bit by coming up with these very different kinds of mobility, which are based on mathematics.”

Centripetal force pushes forward each of the robots in the Tallapragada collection.

To understand, think of a dryer with a few sopping wet clothes that stick to one side as the barrel inside spins. What happens? The dryer starts to vibrate and even takes little leaps off the ground if the barrel whirls fast enough.

That same force is what makes the wheel jump, the fish-like robot swim and the pipe robot crawl, and it could soon make insect-like robots fly.

The research is giving students an opportunity to work on the cutting edge of robotics and mathematical modeling.

Prashanth Chivkula began developing the fish-like robot as a graduate student and has continued as a postdoctoral researcher.

“I want to be a roboticist, and that’s what motivates me every day– to make robots that do something useful in the world,” Chivkula said.

Tallapragada and his team recently moved their operation to a freshly refurbished lab in Clemson’s Fluor Daniel Engineering Innovation Building.

In a recent interview, they pulled back the curtain on how they have managed to make their machines move uncannily like living things:

On a roll: The remote-control wheel, or Spin Gyro, jumps and moves because it has an unbalanced mass spinning inside it. When that mass rotates fast, it creates a force strong enough to lift the robot off the ground. It can jump again almost instantly, without needing to compress springs to reset. The wheel could help future robots travel over rocky or uneven terrain.

Going deep: The fish robot swims using the same idea– an unbalanced mass that spins and sends energy into its tail. By changing how fast the mass spins, the team can control how it dives, turns and moves. It’s extremely energy-efficient compared to other swimming robots and could one day help monitor lakes and oceans or collect water samples without needing a person in a boat.

In the pipeline: The pipe robot crawls through narrow pipes using a spinning mass that makes small bristles on its body rapidly compress and release. The friction from the motion pushes it forward. It could travel through pipes only an inch wide and move fast enough to inspect ducts, gas lines or tight spaces where other robots can’t go. It could also pull cable through long pipe networks.

Taking flight: The newest project in Tallapragada’s lab continues the same theme to create a small flying robot inspired by insects. The same spinning-mass ideas could be used to flap wings at very high speeds, which insect-like flight requires, he said. The work is funded by a three-year grant from the National Science Foundation.

But the Tallapragada team is starting to look even beyond terrestrial airspace– way beyond.

Robots moved by centripetal force could one day help explore other planets’ icy moons, where scientists believe liquid water may lie beneath the surface, Tallapragada said.

A single robot that can roll, jump, swim and fly could navigate ice, leap through volcanic vents and dive into subsurface oceans to search for signs of life, he said.

“I just like working on these new ideas that are very different from what others are doing and seeing them come to physical action,” Tallapragada said. “Once they come into action, that gives me more motivation to go back to the whiteboard and come with more models.”

Alexander Leonessa, chair of the Department of Mechanical Engineering, said the work reflects Clemson’s push to create the nation’s best student experience and accelerate the University’s research profile.

“Projects like the ones in Dr. Tallapragada’s lab provide our students with an opportunity to innovate on the cutting-edge and help shape the future of robotics,” he said. “They show what’s possible when bold ideas, rigorous science, creativity and hands-on learning come together.”