Clemson’s first-ever recipient of a master’s degree, Patrick Henry Hobson, was an early, if unassuming, force in the life of the school. But his educational pursuits a century ago set in motion a current, one that has grown swifter with the passage of time, carrying his family — and the Clemson Family — forward in the noble search for opportunity through learning.

On the 100th anniversary of graduate education at Clemson, we celebrate Pat Hobson’s milestone alongside ours.

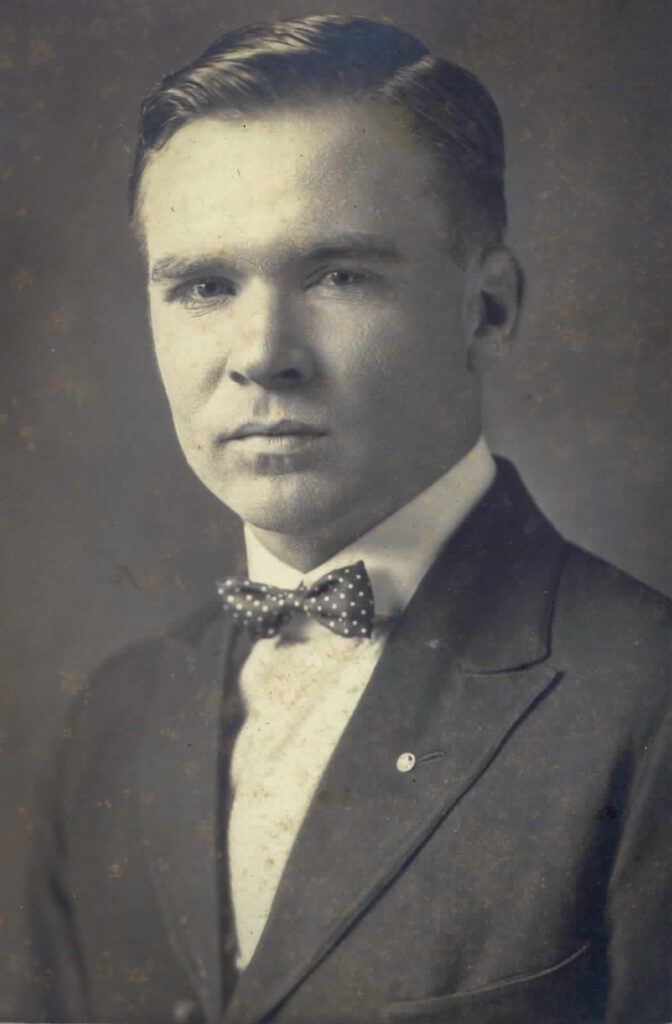

The interests and upbringing of Patrick “Pat” Henry Hobson 1924, M 1924 were unremarkable in most ways for a generation that came of age in the waning years of the first industrial revolution.

Born in 1895, nearly 30 years before he earned his Clemson degree, Hobson was raised as one of eight children on a patch of land in Sandy Springs, South Carolina.

The agricultural community was less than 10 miles from, at that time, Clemson College. And Hobson, a regular on the honor roll at the nearby Denver School, placed a high value on his studies even then.

But higher education was by no means a given. Clemson, close to home, was still a distant possibility.

“It was a time when nobody had much, especially in rural South Carolina,” says Pat’s grandson Rick Hobson. Today, Rick is one of dozens of accomplished Hobson family members who have pursued their own paths in higher education. Rick is a vascular surgeon in Greenwood, South Carolina.

“Poppy grew up very poor,” Rick recalls, using the family’s pet name for their patriarch. According to diary records that the extended family keeps, Pat’s mother passed away, leaving the then 12-year-old and his siblings in the care of their father alone. One way they survived, diaries detail, was by making an annual summer trek to visit an aunt so she could sew and provide their clothes for the year.

“They were self-sustaining,” Rick says of his ancestors. “All their clothes were home-spun, and their father didn’t have the skills for that. So, every summer they would go to one of his sisters’ homes for a week.”

Young Pat learned how to cook during these years, a skill he carried with him throughout his adult life. Children and older grandchildren still fondly recall Poppy’s “left-handed biscuits.”

“He did the dough with his left hand because it wouldn’t taste right if he did it with the right hand,” Rick says, eyes smiling.

It’s just one of many things that the family has always known and loved and remembered about Pat.

He served, he married, he started a family. And then, Pat began his next great adventure.

What happened next, as it turns out, was quite remarkable.

Pat Hobson: Remembered, honored

His work ethic from the time he was a young man. Pat clerked at a couple of department stores in Anderson, worked as a farm laborer, delivered ice, and helped his father with some carpentry.

His curiosity, his sacrifice. In 1917, like many men his age, he enlisted in the U.S. Army as the nation entered World War I.

His focus. Military service, family explains, seemed to have sharpened Pat’s attention and his ambition. After returning home from war, he married his sweetheart, Lena Clarke, started a family, and took a job as a station agent at the Sandy Springs stop on the Blue Ridge Railroad to support them all. Their union would last for 69 years and they had five children — all of whom went on to earn college degrees themselves.

Legacy of learning

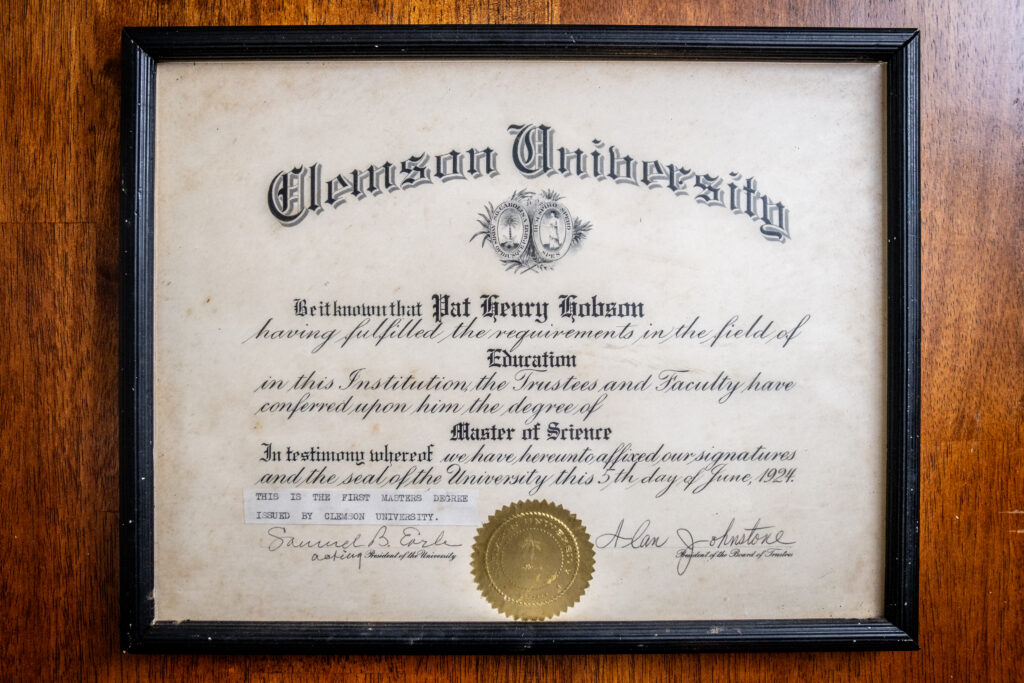

When Pat Hobson enrolled in Clemson in 1921, the average yearly income for a family in South Carolina was $3,300. Tuition and fees cost close to $300, and a college degree was the exception, not the norm, for most Americans. An advanced degree was even more rare, as many colleges — including Clemson until 1924 — did not offer them. Only 8,000 master’s degrees were awarded in all of the U.S. in 1924, the year Hobson earned his degree at age 29.

These were the years just before the Great Depression, and the notion of spending hundreds of dollars on college was unrealistic, if not unimaginable, to most. But Hobson was set on providing a better life for his family, and he believed education was the path to that destination, his family says now.

Hobson’s son, the Rev. Dr. Dick Hobson, now 94, is a resident of Black Mountain, North Carolina. Friends and family often visit his assisted living community in the Western North Carolina community, and from there, he fondly shares stories about his father, Pat.

“I think, for Poppy, his education sort of assured his family members who needed an education would get it,” says the Rev. Hobson. “It was a given.”

That value of an education was reinforced to children, grandchildren and their families up until Pat’s death in 1988. “Poppy” is buried in the Old Silver Brook Cemetery in Anderson.

To this day, Pat Hobson’s ambitions are legendary among his kin. Less known to them, however, was the rarity of what he did at the time. The prestige of his accomplishment was hardly ever part of the stories he shared. And son, the Rev. Dick Hobson, says that growing up, most of the family was not even aware that his father held the first graduate degree ever awarded Clemson.

“Some in the family may have been aware of it, but I was not,” says the Rev. Hobson. “I think most of us were not.”

Pat was determined to get as much of an education as he could, the Rev. Hobson recalls, not simply for his own ambition, but because “he knew his education would ensure that family members who needed (education) would get it.”

The point wasn’t that Pat Hobson earned the first Clemson graduate degree. It was his commitment to making sure he wouldn’t be the last.

Old Reliable

Pat earned a reputation as a hard worker. Classmates referred to him as “Old Reliable,” and his photo caption in the 1924 TAPS yearbook reads: “Pat seemed to be able to carry 30 hours of work with the same ease that he could carry 15.”

It might explain how he finished his B.S. and M.S. at the same time.

“He was not a person who had vacant time. He managed to fill it with creative things or celebrating in some way,” says the Rev. Hobson. Cooking, gardening, socializing with neighbors were favorite activities.

“He didn’t lack for an hour without some event happening.”

Pat Hobson remained a Tiger tried and true his whole life, often attending sporting events with his children and grandchildren and mercilessly ribbing members of his family who earned degrees from other universities. He particularly loved Clemson Baseball.

“I remember sitting in his chair with him at his retirement house and listening to the games on Saturday afternoons,” recalls grandson Rick.

Pat was intentional about his allegiance to Clemson, but the actual impact of a graduate education has surely eclipsed what he could have imagined as a young husband and father.

“To give you a sense of the impact it has had on Clemson as an institution, we’ve now graduated more than 50,000 master’s students,” says John Lopes, Clemson associate provost and dean of the Graduate School. “This year, we’re graduating more than 300 doctoral students. All of that was made possible by what Pat, ‘Poppy,’ started.”

It goes way beyond South Carolina, too, says Lopes, noting that the Graduate School has now graduated students from every state and 152 different countries. “People from all over the world have found their way to the Upstate to build their futures here. And all that was made possible by that kid from Sandy Springs who started it all.”

Hobson put his own Master of Science in education to good use, carving out a distinguished career in education that culminated in a position as superintendent of schools in York County.

And he never lost his zest to learn.

Grandson Ken Hobson, a retired professor of entomology at the University of Oklahoma, grew up visiting his grandfather’s house and recalls watching his father, who earned his Ph.D. in chemistry and who also is named Patrick Hobson, and grandfather talk long and deeply about things to be learned.

“I remember visits down to the old family home in Anderson,” Ken Hobson says. “We would come rolling into his house when I was in elementary school — my mom and dad and four kids. Before long, Poppy would turn to him and say, ‘Have a seat, son,’ and then start asking him questions about what he was working on and what he had learned that year.

“When I started studying biology at the University of North Carolina, I’d walk in the room, and Poppy would say, ‘Ken, what have you learned this year?’ He wanted to understand what was new in the world. He had such a love of knowledge,” says Ken, smiling and nodding over scrapbooks and memorabilia gathered before him, recalling his grandfather’s life. “It all springs from the same fountain.”