While millions of Americans are expected to spend more than $950 billion on gifts this holiday season, few will stop to ponder the piece of technology that will make those transactions possible – the barcode.

Jordan Frith, with a barcode freshly inked on his left bicep, is an exception. Frith is the Pearce Professor of Professional Communication at Clemson University, and the author of the new book, “Barcode.”

“During my research, I just really kind of fell in love with barcodes as an object,” Frith said, adding it was his favorite book he’s ever written.

“Barcode” dives into the technology that has existed for nearly 50 years and connects billions of physical objects and digital databases. Published by Bloomsbury Academic and part of the “Object Lessons” series, Frith’s latest book is a tight read stuffed with nuggets of barcode minutiae. The premise is to pitch the potentially mundane – think the remote control, questionnaire or egg – and develop digestible takeaways of its cultural impact for a broad audience.

As he promised inside the 134-page book, Frith tattooed its ISBN to celebrate its November publication.

“I wrote in the book I was going to get a barcode tattoo, and I don’t want to lie to my readers,” he said.

The book tracks the history of barcodes, which includes the first product being scanned with an official Universal Product Code – a pack of Wrigley’s gum in 1974 – to the emergence of QR codes as a replacement for paper menus during the COVID-19 pandemic. Along the way, Frith explores moments when barcodes have shifted the culture. A media gaffe over the barcode worsened the political fortunes of President George H.W. Bush in 1992.

“It makes the global economy, retail system and shipping and logistics possible,” Frith said of barcodes. “It’s about looking at the things that might be mundane, but how they’re actually super interesting. They shape our lives.”

Department of English chair Will Stockton praised “Barcode” as accessible to academic specialists and lay-people, serving as a “great introduction” to Frith’s work.

“‘Barcode’ is an excellent example of Professor Frith’s work to document and trace the history of the technological infrastructures that underwrite modern communication,” Stockton said. “Who would have thought that a barcode, which most of us no longer think about, had so much to tell us about the history of global markets and human interaction?”

Grocery store beginnings

Frith spent a week in the George Goldberg archive at Stony Brook University in New York in summer 2022, thumbing through documents created in the 1970s.

According to his findings, Drexel University graduate student Bernard Silver overheard a pitch for an automated supermarket checkout in the 1940s. Silver mentioned it to a peer, Joseph Woodland, and the two moved forward to patent the barcode in 1952. From there, an ad hoc committee of stakeholders in the grocery industry litigated whether it was feasible to install a barcode system.

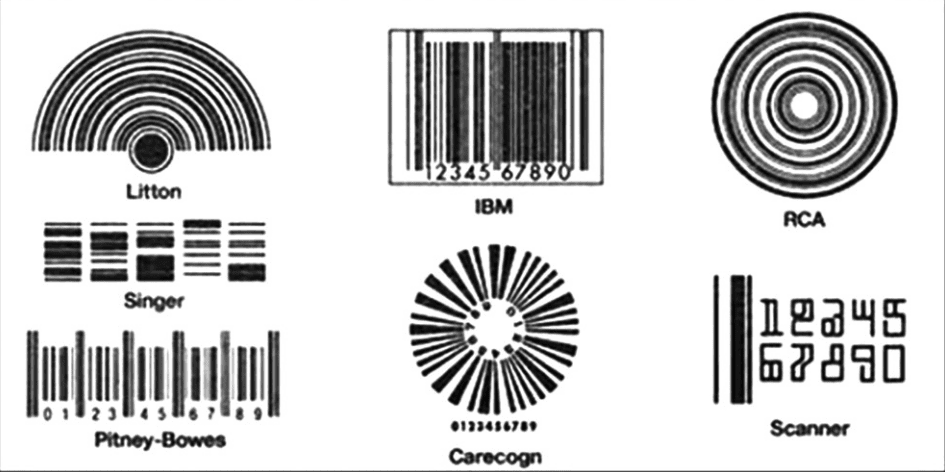

Seven finalists emerged, each visually unique. The winner, IBM, was selected over the RCA “bullseye” crafted by Woodland. The winning design was slightly modified into the UPC-A barcode. It contains 15 pairs of black lines and white spaces printed over a data string. Three line pairings hold no data, Frith writes, and a digit is determined by the thickness of each line in a pair and the amount of space between the lines.

In the culture

There haven’t been seismic updates to the tech since its implementation in the ’70s, but its history has evolved by the decade.

The first prominent example of a barcode appearing in a science fiction film was James Cameron’s 1984 “The Terminator.” There have been recent campaigns pushing awareness around human trafficking victims tattooed with barcodes. Barcode-inspired buildings are in China, Norway and Russia.

Conspiracies have swirled in some religious pockets over the UPC barcode being the “Mark of the Beast,” a prophecy found in the Book of Revelations in the Bible.

In February 1992, President Bush visited a National Grocers Association convention and was shown a barcode and scanner. Thanks to The New York Times, an interaction at the scanner further fueled the political line of attack that an isolated and elitist Bush was out of touch with “ordinary” Americans. The story was hogwash.

As readers will discover, a media narrative was born and the damage dealt. It wasn’t the lone reason Bush lost to Arkansas Gov. Bill Clinton, Frith writes, but it didn’t help his reelection bid.

“It was something that dogged him through the entire campaign,” Frith said. “Somehow, supermarket technology and this narrative helped shape who won a presidential election.”

Months after the incident, Bush ironically presented the National Medal of Technology to Woodland for his role in inventing the barcode. He cracked to Woodland that he had “seen firsthand how impressed I am about how barcoding works.”

“Amazing,” Bush said.

It was that moment the barcode had become “taken for granted,” Frith writes, as the UPC barcode turns 50 years old next June.

Where to buy

“Object Lessons” books are marketed at an intentionally affordable prices for all audiences. “Barcode” is available on Amazon for $14.95.

Kenneth Burke says that we’re bodies that learn language. N. Katherine Hayles wrote of ‘Writing Machines.’ Dr. Jordan Frith is a prolific writing body/machine. He writes about people, places and the technologies that mark and situate us in a world of material and symbolic power. Not only does his research at Clemson help all of us find our way in a complex world, but it also inspires graduate and undergraduate students to write their way into the world as emergent scholars and professionals.

DAVID BLAKESLEY, Campbell Chair in Technical Communication

About the author

Jordan Frith is the Pearce Professor of Professional Communication at Clemson University. A native of Fairfax, Virginia, Frith came to Clemson in 2019 after spending six years as a professor in the Department of Technical Communication at the University of North Texas in Denton, Texas. He earned his Ph.D. in communication, rhetoric and digital media from North Carolina State University in 2012. Frith has a deep interest in communication infrastructures. He is the author of six books, more than 40 journal articles and serves as the editor-in-chief of “Communication Design Quarterly.”

Get in touch and we will connect you with the author or another expert.

Or email us at news@clemson.edu