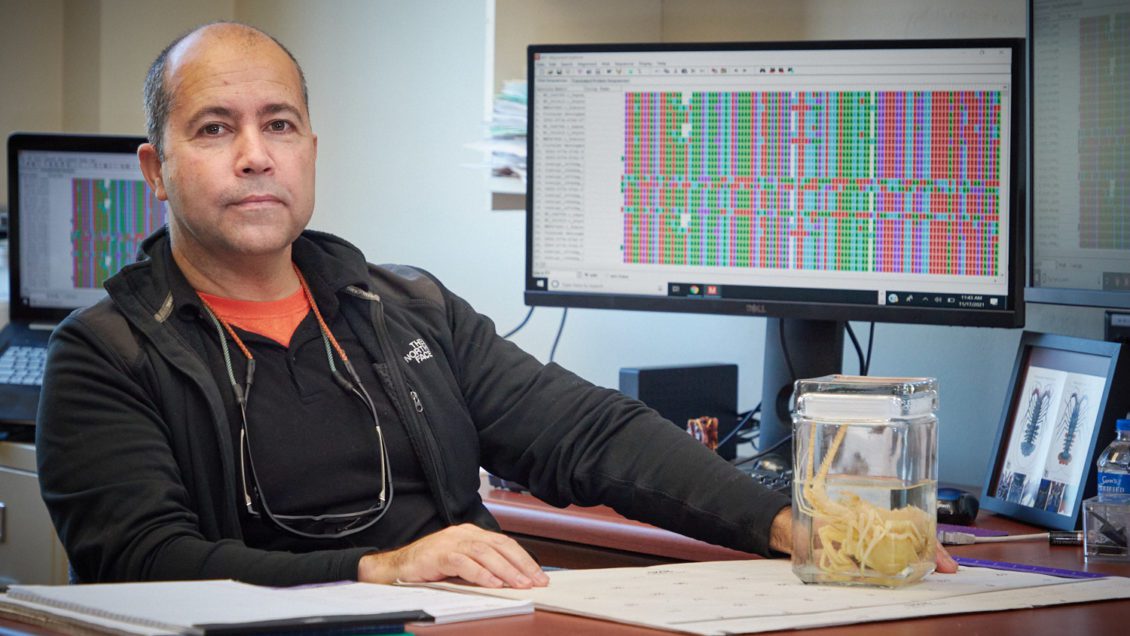

Clemson University marine biologist J. Antonio Baeza’s recent discovery of two new marine species has him looking at the future and the past.

The marine invertebrates identified by Baeza — a parasitic worm that attacks the eggs of crabs found off the Chilean and Peruvian coast in the southeastern Pacific Ocean and a tiny shrimp from the waters of Madagascar with the potential to become part of the lucrative ornamental aquarium industry in the Indo-Pacific Ocean — could have future implications for the sustainability of important fisheries and marine industries.

But they pay homage to the past, as the names Baeza chose honor the indigenous people in the areas where they live.

“I think it’s important to remember the past while we’re looking to the future,” he said.

Voracious egg predators

Two years ago, Baeza discovered a new species of nemertean worm while researching parental behaviors and reproductive performance of the Caribbean spiny lobster Panulirus argus in the Florida Keys. The broods of eggs where the worms were found had many dead embryos and empty embryo capsules.

Caribbean spiny lobsters are vital for the marine ecosystem because they are prey for many predators, including sharks, large fish such as grouper and snapper, turtles and octopuses. Landings of the commercially lucrative species have decreased over the past decade. One contributor could be Carcinonemertes conanobrieni, the worm Baeza discovered and good-naturedly named after comedian Conan O’Brien.

Nemertean worms belonging to the genus Carcinonemertes inhabit the southwestern and northwestern Atlantic Ocean, the Caribbean Sea, the southwestern Indian Ocean and the north and the southwestern Pacific Ocean. But before Baeza’s discovery, none had been identified in the southeastern Pacific Ocean.

Hole of knowledge

“There was a hole of knowledge in the southeast Pacific, so, working with colleagues in Chile, we went hunting for these types of species in that area, knowing the effect these parasites can have on species that are intensively used (fished) by humans,” said Baeza, an associate professor in the College of Science’s Department of Biological Sciences.

Researchers identified the new nemertean worm species in egg masses of two commercial crabs that inhabit the central-north Chilean coast. The new species, Carcinonemertes camanchaco, has two ovaries on each side of the intestines and produces a simple, not ornamented, mucus sheath.

“The crab species, which are in the same family as Dungeness crabs, are already impacted by fishing. If we have an outbreak of this parasite, the fishery can collapse. It has happened in other fisheries,” Baeza said. “We are trying to understand the worm’s effect on the crab’s reproduction and gain the scientific knowledge necessary to manage the fishery towards the goal of sustainability.”

Baeza named the new parasitic worm after the Camanchaco, indigenous people who inhabited the Pacific coast from southern Peru to north-central Chile for thousands of years and relied on the area’s abundant marine life.

Baeza’s research on the Carcinonemertes camanchaco was published in Scientific Reports.

Tiny shrimp, huge possibilities

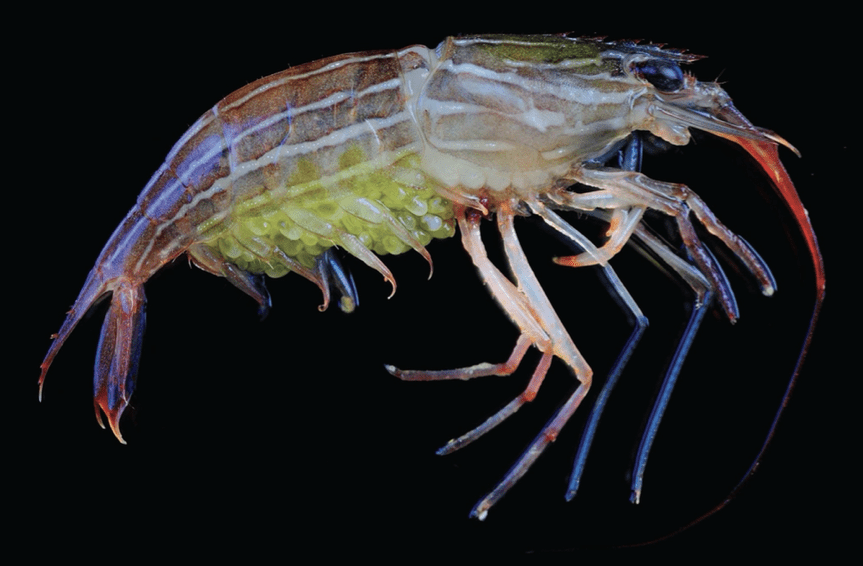

The new shrimp species Baeza identified, the Lysmata malagasy, could be important to the ornamental aquarium industry and potentially become a new fishery in Madagascar and east Africa.

Peppermint shrimp are scavengers often added to saltwater aquariums to “clean” the tanks by consuming detritus, uneaten food and decomposing organic matter.

“It’s a multi-million dollar industry. If you go to a pet store, especially in Florida or on the East Coast, they sell these peppermint shrimp by the millions,” Baeza said. “Besides providing this cleaning service, they are also beautiful.”

Baeza named the new species after “Malagasy,” the native inhabitants of Madagascar where the specimen was collected. “Malagasy’ is the English version of the French word “Malgache,” the word used for both the people and their language.

Baeza said he sees an opportunity for Madagascar to generate a new industry, especially if marine biologists can learn enough about the biology of the new species to cost-effectively produce them in mass in an aquaculture facility.

Details of Baeza’s research on the Lysmata Malagasy were published in the European Journal of Taxonomy.

The College of Science pursues excellence in scientific discovery, learning and engagement that is both locally relevant and globally impactful. The life, physical and mathematical sciences converge to tackle some of tomorrow’s scientific challenges, and our faculty are preparing the next generation of leading scientists. The College of Science offers high-impact transformational experiences such as research, internships and study abroad to help prepare our graduates for top industries, graduate programs and health professions. clemson.edu/science

Get in touch and we will connect you with the author or another expert.

Or email us at news@clemson.edu