CLEMSON, S.C. – For every child who tenderly pressed a flower or a four-leaf clover inside a beloved book, there is a treasure awaiting at Long Hall. A much-needed renovation has given new life to the Clemson University Herbarium, which houses about 100,000 plant specimens that have been carefully preserved and stored for the future.

Curator Dixie Damrel said the new on-campus facility located in the basement of the 83-year-old building is a dream come true, though many – including some who walk past its doors – are not quite sure what role an herbarium plays in the world of science.

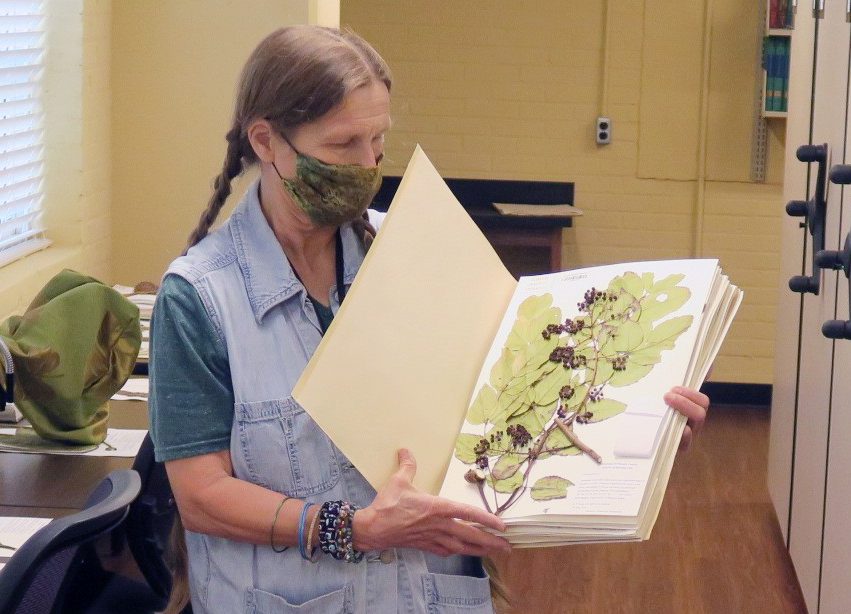

“An herbarium is a collection of documented, dried and pressed plant specimens that people use for many, many different types of plant research and plant study,” Damrel said.

Damrel’s use of the word “documented” is the critical part of what happens at the facility, which is housed and operated by the College of Science’s department of biological sciences.

“Each one of our pressed plant specimens serves as an official document that a certain plant was collected at a certain place on a certain day,” Damrel said. “It’s like a piece of evidence. I like to think of the herbarium as a big evidence room of plant diversity on Earth, whether it’s a small location or a worldwide scope.”

Botanists collect each specimen using specific procedures. The plants are dried and mounted.

“Somebody actually identifies them under the ’scope and we make a big label that details everything about the collection process,” said Damrel, who became full-time curator of the herbarium in 2008 and is now continuing that role on a part-time basis. “We have mounters that mount the pressed and dried specimen in a way that shows off all the characteristics.”

The expertly identified specimen can then be used as a reference for other people to identify plants that they collect. Herbarium specimens are also used extensively for research ranging from studying flower morphology and color to understanding thermal tolerance, to comparisons of leaf morphology of invasive plants in their native and introduced ranges. At Clemson, the collections are also used for plant biology teaching labs and undergraduate research projects.

Matthew Koski recently received a $455K grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to study how flowers adapt to heat and cold.

“Herbaria are invaluable for botanical research and teaching. They are essentially ‘time capsules’ of historical plant traits and genetic material that are key for addressing questions about how global change has impacted plants,” said Koski, an assistant professor in biological sciences who specializes in floral adaptation. “I am thrilled that we are investing in and improving such a critical resource.”

Cierra Sullivan works on the ecophysiological consequences of leaf variegation and how climate affects the expression of floral color. This line of study makes for frequent visits to the herbarium to conduct research.

“An herbarium is to a plant scientist what an insect collection is to an entomologist — a timeless collection of information and beauty for research or for simply viewing,” said Sullivan, a graduate student in biological sciences. “You don’t have to strictly be a plant scientist to enjoy what herbaria have to offer. I hope the renovation attracts more visitors to Clemson’s herbarium, including those who study something that has an interaction with plants and even those who just think plants are pretty.”

Specimens can remain intact for hundreds of years, but they need an environment that supports proper storage.

The university’s original herbarium was destroyed in the Sikes Hall fire of 1925, though it was restarted almost immediately thereafter and still includes some pre-1925 specimens. When Damrel came aboard as curator more than a decade ago, the collection was housed behind Long Hall in the sub-basement of the Bob and Betsy Campbell Museum of Natural History. This museum also contains an extensive collection of vertebrate specimens, most of which have remained in the original building. The space vacated by the herbarium specimens’ move to Long Hall has created even more display opportunities and room for expanding the vertebrate collection for teaching, research and outreach.

Dried plants stored on paper in an old basement was far from ideal. Damrel recounts one late-night call from campus security letting her know that a nearby water main had broken. She headed straight to the herbarium to begin safeguarding the treasures.

The space was also undersized. Squeezing in just two people to see the main collection was a tight fit. Therefore, renovation plans had long been in the works, but the 2008 recession put them on hold.

“I was literally about to put a shovel to the concrete before the recession hit,” said Mike Moore, building manager and project coordinator for the department of biological sciences.

The project was finally completed this year and was the culmination of a significant amount of work in Long Hall.

“It opened up some rooms that weren’t being used and made them very functional,” Moore said. “We gave them a classroom, a workroom, and an isolation room for new samples that need to be quarantined until they are free of insects and fungi and are safe to add to the collection.”

The new facility also includes a compactor system for plant specimens that adds even more usable space by allowing cabinets to be pulled together.

“Before we moved, things were so packed that it almost pulverized the specimen when you filed it,” Damrel said. “Now, there is room to work, study and protect the collection. It’s like a dance floor. It’s wonderful.”

Researchers of all disciplines now have room to study and explore the herbarium, including special areas such as the Jesse P. Perry Pine Collection, which contains approximately 600 specimens. This collection is an important record of pines and pine cones from Mexico and Central America and is one of only a handful of specialized pine collections in the United States.

Professor and chair of the department of biological sciences Saara DeWalt said the renovation is a win-win-win, allowing for the expansion of the herbarium’s collection in the new space, as well as the expansion of the vertebrate collections in the vacated space. She has also used the collection for her own plant ecology research on invasive plants in their native and introduced ranges.

“The last win is that we’ve converted a dusty, dirty space into bright, airy, useful and beautiful rooms in the basement of Long Hall,” DeWalt said.

The project was made possible by funding from the LeGrand McIver Sparks ’41 and Mary Sears Sparks Endowment (A Class of 1941 Initiative), the Professor John E. Fairey III Quasi-Endowment for Natural History, the Biological Sciences Excellence Fund, and the Friends of the Natural History Museum. It also included university investment in teaching and learning spaces.

The herbarium houses specimens from all over the globe, though its concentration is local and regional. Researchers from around the state, nation and world can also use the collection online. Through funding from the NSF, the collection is almost entirely digitized and available through the SouthEast Regional Network of Expertise and Collections (SERNEC) portal. When campus is once again bustling with activity, the new location will offer that in-person experience as well.

“Making a specimen is not hard – it’s not high dollar,” Damrel said. “But it is invaluable. It is priceless.”