Collaborations increase the impact of Clemson research, including future treatments for the fatal brain condition caused by Naegleria fowleri

When Jillian Milanes read a scientific paper from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center about an enolase inhibitor that effectively killed a specific type of brain cancer cell, it immediately caught her attention.

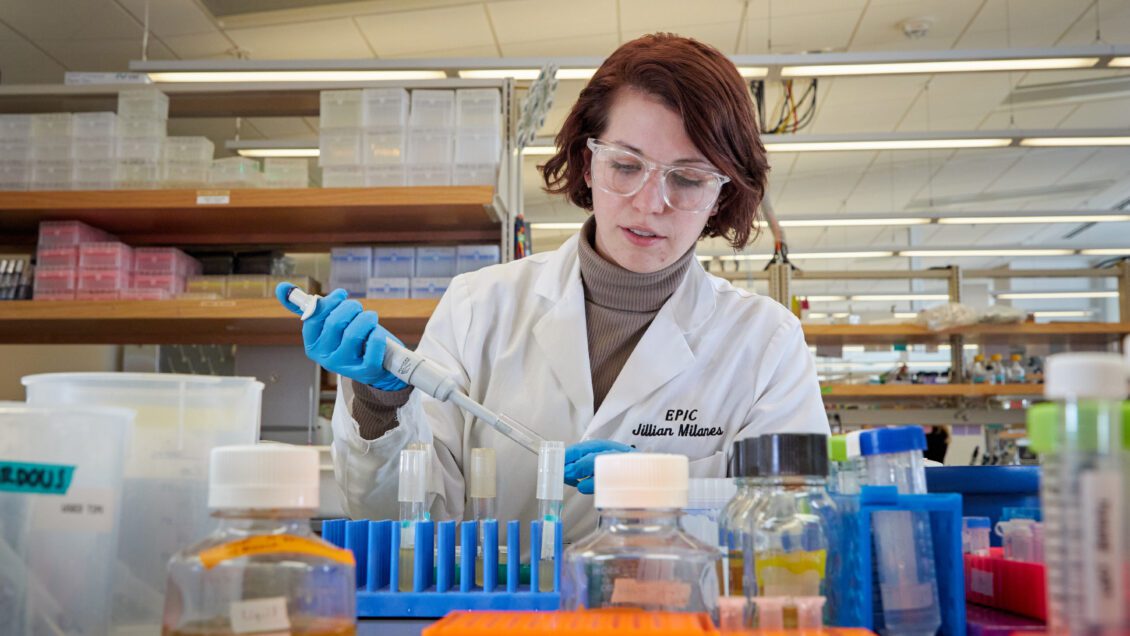

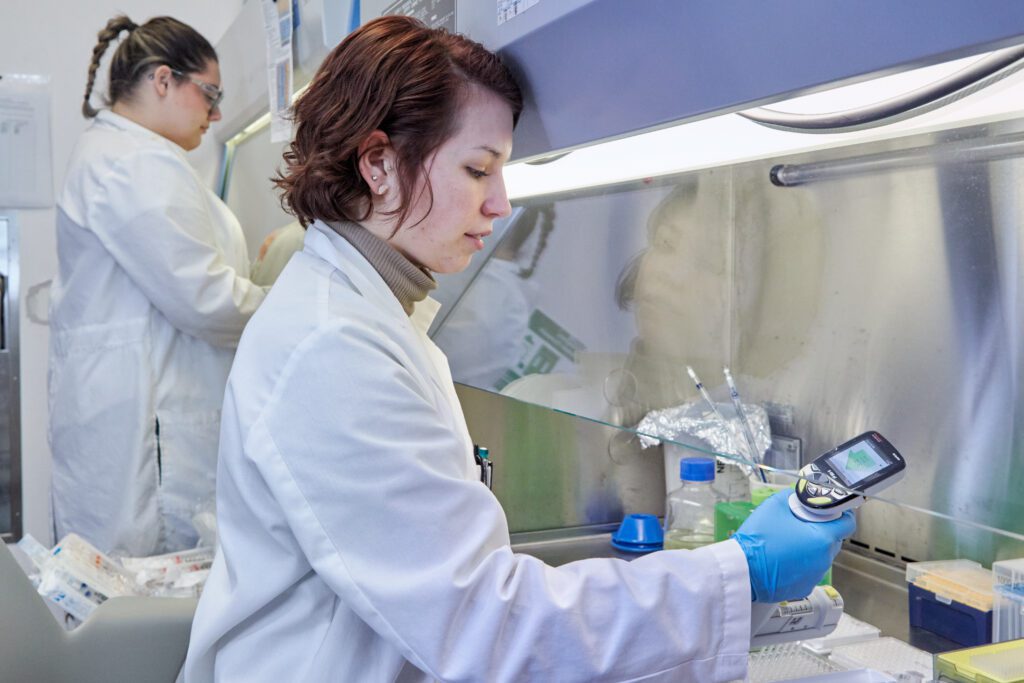

Milanes, a graduate research assistant at Clemson University, is not a cancer researcher. Instead, she is a scientist in James Morris’ lab at the Eukaryotic Pathogens Innovation Center, and she is studying something less known and far less common than cancer but equally as devastating — the brain-eating amoeba Naegleria fowleri.

“It’s a terrible disease, and the drugs available are not great,” Milanes said.

Milanes’ research has shown glycolysis, a series of reactions that extract energy from glucose, is essential to cell growth. She said that exploiting sugar metabolism pathways could be helpful in the development of new therapeutics. Enolase is an essential enzyme involved in glycolysis.

The MD Anderson Cancer Center research caught her attention because the Morris lab does viability assays testing random compounds on parasites in vitro to see if they impact growth. Several things about the research fueled her excitement:

- It involved enolase.

- The researchers knew the mechanism of action.

- They had tested the compound in rodent models, meaning it wasn’t toxic to mammals.

- The compound crossed the blood-brain barrier, something that’s important for treatment of Naegleria fowleri infection.

Milanes asked Florian Muller, the MD Anderson researcher, to collaborate so they could try his compounds on the brain-eating amoeba.

Several of Muller’s compounds inhibited cell growth in vitro. A second assay showed the compounds also inhibited the enolase enzyme found in Naegleria. In addition, the concentration of drugs needed to inhibit cell growth was incredibly low compared to any other drugs Milanes has tested.

When they delivered the compound systemically in a rodent model, it appeared the amoeba slightly altered its metabolism to reduce its toxic effect.

“The amoeba extracted from the brain are still sensitive and killed at pretty low levels, suggesting we did not get enough in the brain,” Morris said. “So, we just need to get the levels in the brain high enough.”

The researchers believe if the agent was delivered quickly and directly to the site of the infection, the amoeba would not be able to alter its metabolism to reduce the compound’s toxic effect.

“Because humans infected with the pathogen commonly receive drugs intrathecally directly into the cerebrospinal fluid — the fluid that surrounds the brain — we are pursuing that sort of delivery in rodents now to avoid slow exposure,” he said.

The collaboration is just one example of EPIC researchers working with scientists across the country to find better treatments for diseases caused by eukaryotic pathogens, including malaria, amoebic dysentery, sleeping sickness, Chagas disease and fungal meningitis. Many eukaryotic pathogens are classified as bioterrorism agents or neglected tropical diseases.

EPIC also encourages collaboration through its annual Cell Biology of Eukaryotic Pathogens (CBEP) Meeting. It brings together some of the best parasitic and fungal disease researchers in the country, helping them connect with other researchers involved in the cell biology of various eukaryotic pathogens.

At CBEP, researchers share their findings on diseases that threaten billions of people worldwide and bounce around ideas by discussing their research with others.

You have all these minds in one place and have a diversity of thoughts to get new research ideas you wouldn’t have otherwise.

Kerry Smith, EPIC director

Dennis Kyle, who earned a degree in zoology from Clemson in 1984 and is now the director of the Center for Tropical and Emerging Global Diseases at the University of Georgia, said researchers must be able to reach outside their universities.

“Even though they have built a very nice group of people working on parasites and other eukaryotic pathogens in EPIC, there are still gaps in what they do versus what other people do,” said Kyle, who serves as a member of the external advisory committee for EPIC. “It has been my personal experience in research that many of the most viable collaborations are where you reach out to people with expertise, assays or ideas that differ from mine and collaborate.”

Kyle continued, “The Clemson EPIC groups have built a nice reputation, so people look to them for collaboration opportunities.”

But collaboration that advances knowledge of how eukaryotic pathogens work doesn’t always have to come from the outside. EPIC has built a strong cohort of Clemson researchers approaching similar problems in different pathogens.

“There’s a real synergy that comes out of that. Even though one project may be on Cryptococcusand another is on a trypanosome, some of the same approaches and problems pop up, so they learn from each other,” he said.

Get in touch and we will connect you with the author or another expert.

Or email us at news@clemson.edu