New evidence that an ancient river system flowed from Canada’s western mountain ranges to the Labrador Sea is raising questions about the impact it may have had on Earth’s climate millions of years ago and could provide clues to what the future climate might be like, Clemson University researchers said.

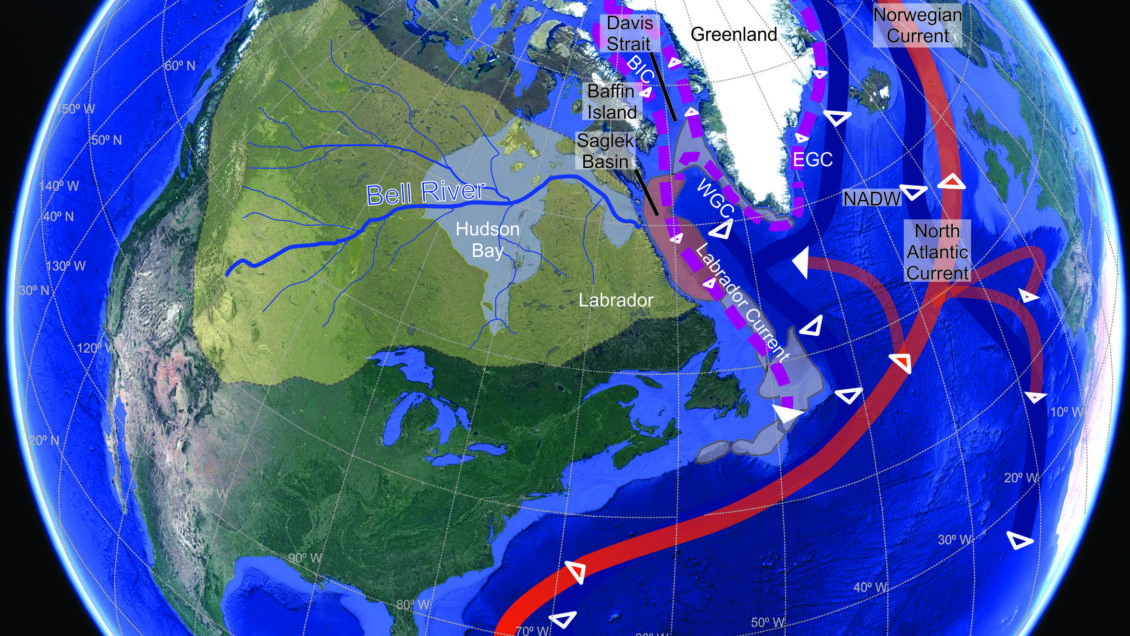

Scientists have long hypothesized that the now-extinct Bell River and its tributaries flowed east about 3-30 million years ago, until the Laurentide Ice Sheet wiped it from the landscape during the Ice Age.

The river would have been mighty enough to rival the modern-day Mississippi or Amazon, with tributaries extending north to the Arctic and south to what is now the United States.

Researchers said they have found fresh evidence of the river’s existence by comparing sediment deposits about 1,800 miles apart and analyzing shells left by marine life of the time.

“This is concrete evidence from multiple angles, not just the sedimentology aspect but also the marine side of it,” said Julia Corradino, who was a master’s student in hydrogeology when she participated in the research.

Researchers detailed their work in the new edition of GSA Bulletin, a journal published by The Geological Society of America. The authors included Corradino and her master’s advisor, Alex Pullen, an assistant professor of environmental engineering and Earth sciences at Clemson.

One set of ancient sediment samples came from Alberta and Saskatchewan, near where researchers believe the river systems’ headwaters formed. Another set came from wells drilled into the bed of the Labrador Sea in what is now known as the Saglek Basin Researchers believe the basin is where the extinct river emptied into the sea.

They used uranium-lead dating to compare zircon crystals in the two sets of samples. The results suggested the two sets of sediments were from the same source and that they were carried across the continent by the ancient river system, researchers said.

Researchers also analyzed shells and shell fragments of ancient bivalve marine organisms found in the cores extracted from the underwater wells.

“When they build their shells, they take on the chemistry of that sea water,” Pullen said. “That river, we think, changed the chemistry of the Labrador Sea such that we can take these shells and measure some isotopes and say, ‘This is not what the modern Labrador Sea is like now.’”

For Pullen and Corradino, the new evidence that Bell River did exist has raised questions about how the massive amounts of freshwater flowing into the sea would have affected the circulating currents of ocean water that help drive weather patterns.

It’s a question that could be relevant to the modern world. The Greenland Ice Sheet is melting freshwater into the sea in the same area where the Bell River is believed to have emptied freshwater into the sea.

Scientists working separately from Pullen and Corradino believe the freshwater from the melting ice sheet is slowing Atlantic meridional overturning circulation and that it could have major implications for the global climate.

Whether clues from the ancient Bell River system can help explain the modern climate remains an open question, but Pullen has some ideas for next steps.

Next for geologists is to determine more precisely when the river died, he said. Researchers believe it happened sometime around the start of the last Ice Age, when glaciers formed and grew to cover what is now Canada and northern parts of the United States.

Pullen would like to know if the river died and then glaciers started to form in the Northern Hemisphere, or if the opposite happened– glaciers shut down the Bell River, which then amplified the formation of glaciers.

A team of researchers from across Canada and the United States came together to make the research possible.

“The Bell River was an enormous river system, and the new insights we’ve gained required the collaboration of researchers from across the U.S. and Canada,” said Andrew L. Leier, a co-author on the GSA Bulletin article and associate professor in the School of the Earth, Ocean and Environment at the University of South Carolina.

Corradino said the research helped broaden her knowledge beyond the bounds of hydrogeology, making her a more well-rounded geologist. She is now pursuing a Ph.D. in engineering and science education at Clemson and wants to use her experiences to help educate a new generation of geologists.

“This is a huge story to tell,” she said, “and I love telling stories.”

The GSA Bulletin article is “Ancestral trans-North American Bell River system recorded in late Oligocene to early Miocene sediments in the Labrador Sea and Canadian Great Plains.”

Authors are Corradino, Pullen and Austin Bruner, all of Clemson; Leier, David L. Barbeau and Howie D. Scher, all of the University of South Carolina; Amy Weislogel of West Virginia University; Dale A. Leckie of the University of Calgary; and Lisel D. Currie of the Geological Survey of Canada. Pullen is listed as the corresponding author on the paper.

Get in touch and we will connect you with the author or another expert.

Or email us at news@clemson.edu