CLEMSON — The beginning of the end of Melissa McCullough’s naval career started on a late-night run to pick up sailors who had been off base.

As bowman, it was her job to throw the line off the small boat so that it could be tied to the dock. The boat crashed into the dock, sending McCullough flying.

McCullough said she landed on her back, blowing out three vertebrae. The injury was painful and it eventually dashed her hopes of becoming an officer.

But if it hadn’t happened, she may never have found the purpose she has at Clemson University.

McCullough is pursuing her Ph.D. in bioengineering under the guidance of Delphine Dean while teaching and working full-time as the bioinstrumentation lab manager.

Now McCullough’s academic work and service to her country are earning her some recognition that colleagues said is well deserved. She is among 60 U.S. service members, veterans and military spouses who have been named to the 11th class of Tillman Scholars.

The scholarship comes from the Pat Tillman Foundation, named for the former Arizona Cardinal who left his lucrative football career to join the U.S. Army and was killed by friendly fire in Afghanistan. Honorees are sharing in more than $1.2 million in scholarship funding this year.

The journey from enlisted sailor to aspiring professor was one that McCullough never dreamed she would take.

“This teaching thing — it really has turned into something I was meant to do,” McCullough said. “Unless everything in my life had happened the way it did, there’s no way I would have gotten here.“

Dean, the Gregg-Graniteville Professor of Bioengineering, said it’s fun to work with McCullough, who brings a wealth of experience and a unique perspective to their work. She is well qualified for the scholarship, which recognizes recipients’ service, leadership and potential, Dean said.

“She has these big goals, both in her current projects and for her long-term career,” Dean said. “She wants to help people. Her long-term goal is to train and educate up-and-coming engineers.”

For McCullough, the road to Clemson started in Virginia. After high school, she enrolled at Tidewater Community College and worked at Dollar Tree.

McCullough enlisted in the Navy after receiving a call from a recruiter, following in the footsteps of her father, a naval electrician’s mate. She liked the discipline and structure of the Navy and wanted to become an officer.

“I went for the hardest training I could: the electronics technician rating ,” McCullough said.

[vid origin=”youtube” vid_id=”AqRKCqVdrR8″ size=”medium” align=”left”]

She trained to fix satellite communications systems, and that’s what she did at her first duty station. But after the 9/11 terror attacks, McCullough was transferred to Italy, where she found the scope of her work expanded.

“I fixed everything from sewage tank sensors to closed-caption television,” McCullough said. “I fixed cars, I fixed everything; forklifts, anything. And that really taught me I could apply the knowledge I have.”

She said she was stationed on Sardinia when she was hurt in the boat’s collision with the dock.

“It was a super painful injury,” McCullough said. “All my muscles just freaked out. I thought I couldn’t walk at first, but once it calmed down and everything started healing, my motions came back.”

At the time, McCullough was a junior enlisted sailor who lived alone off base. Senior enlisted sailors made room for her in the barracks and assigned a rotating crew to take care of her while she healed.

It’s an experience that has stuck with her.

“Nobody told them how to do it — they just did it,” McCullough said. “They didn’t have to do it as well as they did, certainly. And I think like that. That’s how my leadership is — you take care of folks.”

She was honorably discharged and enrolled at Old Dominion University, where she received her Bachelor of Science in electrical engineering technology.

After graduation, McCullough began working for engineering contractors who did work with the U.S. Department of Defense and State Department. For about five years, she traveled the world, designing security systems, deterrents, radars and people monitors.

Her work took her from Baghdad and Kabul to Benghazi and Sudan.

The work was lucrative, high risk, high speed and high intensity, McCullough said.

“I was doing mission after mission,” she said. “I did full deployments. I would get the flak jacket and helmet. I would deploy out with the military folks.”

It took a toll on her health.

McCullough ended up with stress sickness, which came with ulcers and high blood pressure, she said. It was time to dial things down.

By this time, she had settled in Charleston. She took classes at Trident Technical College, and then headed to Columbia, where she continued her studies at Midlands Technical College.

When it was time to go back to work, she found a job listing at Clemson. She remembers applying for the job and a transfer as a student on the same afternoon, and she got both.

“I thought I would stay here a year or two and get some more schooling and fill up my bank account again and then off I’d go,” McCullough said. “I thought I’d go back to contract engineering overseas.”

But she found something at Clemson: a calling.

McCullough started teaching, and Dean let her try new things. A Creative Inquiry course that centers on a bionic arm took off, earning great reviews from students and faculty members.

“I was able to run teams and show kids how to fix things and make things,” McCullough said. “When I came up with ideas to solve problems, they did them — and they worked!”

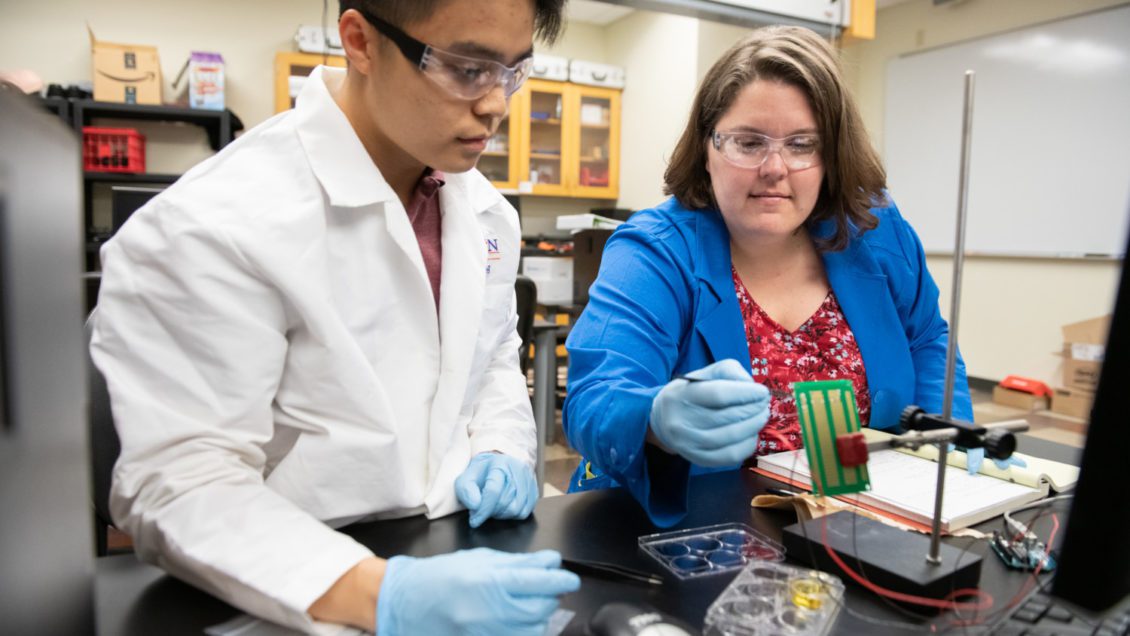

Quan Le, a rising senior who works as McCullough’s research assistant, said that she has become a mentor who has taught him a lot.

Among the most important lessons: “It doesn’t matter where you come from or who you are,” Le said. “You can get there if you have a goal in mind.”

McCullough said her success boosted her confidence and helped convince her to push hard on graduate school.

Now McCullough wants to be a tenure-track professor. She is developing a urinalysis device aimed at early detection of chronic kidney disease and estimates she has a year or two left before getting her Ph.D.

Her story, she said, could not have happened any other way.

“I’ve really found what I’m supposed to be doing, and that is incredibly cool,” McCullough said. “I get really giddy when I think about it. I don’t know how to express it without a big grin on my face.”

Martine LaBerge, chair of the department of bioengineering, congratulated McCullough on her scholarship.

“Melissa has brought her unique experience and talents to bear on the challenges students, faculty and staff face in the department of bioengineering,” LaBerge said. “As a Tillman Scholar, she is well positioned to maximize and deepen her impact.”

To apply for a Tillman Scholarship, contact the Office of Major Fellowships at 864-656-9704 or fellowships@clemson.edu.

Get in touch and we will connect you with the author or another expert.

Or email us at news@clemson.edu