Like most farmers across South Carolina, Chris Stevens is struggling to fight high costs caused by inflation so he can keep his chin above the waterline.

So, when he saw social media advertisements for a fertilizer product that claimed to be super-concentrated with the nutrients required to prime his Horry County hay crop, the crop insurance agent for AssuredAg LLC did the math and jumped at the opportunity to try it.

The product claimed to contain 25 units of nitrogen per gallon. That added up to a 50% reduction in fertilizer costs on Stevens’ 30-acre ryegrass crop.

Stevens applied the product for the 2022 growing season, but it wasn’t long before he realized something was wrong.

“We saw absolutely no results. There was no change in look like we would normally see,” Stevens said.

So, Stevens reached out to the company, and was asked to take some photos, set up some test plots and apply the product again. Once again, there were no results.

It wasn’t long before Stevens did some research and realized it was all smoke and mirrors.

The online reviews were vague and referenced cities that didn’t exist, and the results the company claimed were validated by university studies were not true. Several of the claimed university studies had never even been conducted.

When Stevens reached out to the company, they offered him a product refund in exchange for signing a nondisclosure agreement, but that didn’t sit right with Stevens.

“I wasn’t interested. I work with a lot of farmers, and I guess I feel a sense of obligation to share what I’ve learned,” he said.

In the end Stevens spent $10,000 on the fertilizer product and figures he lost nearly $5,000 on the failed ryegrass crop.

“After seeing no results, we didn’t apply anymore of the product. The rest of it is still sitting in its containers,” Stevens said.

Steps to minimize risk and costs

Consumers can take steps to minimize their risk when purchasing fertilizers, says Brad Stancil, assistant director of the Clemson University Department of Fertilizer Regulatory and Certification Services.

Stancil leads a small team of inspectors that enforce Section 46-25-10 of the SC Code of Laws pertaining to the manufacturing and selling of all commercial fertilizers in South Carolina, but he says it is tough to regulate internet sales.

“Many of them don’t have an outlet or brick-and-mortar store. They are selling through what they call ‘dealers,’ but the dealers are not really named. They’re just guys that have agreed to sell a product to make money. Even if the product has been sampled and tested, the dealers can make claims about the product that aren’t true. You find these products all over social media and Craigslist,” Stancil said.

Some consumers are also looking to industrial by-products like sludge, wood ash, compost, liquids and others to help feed crops and save money.

But by-products must be approved by the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control before they can be applied to land. Once they are approved by DHEC, Clemson may register the by-product as a fertilizer, lime, or soil amendment. In some cases, Clemson might require a research trial before a by-product is registered.

“Some of them are fine. Some of them have calcium and other things in them that crops need. Some people buy those and blend them in with other fertilizers. But it could also be detrimental to your crop or garden, and it could harm the environment or drinking water depending on what the product is,” Stancil said.

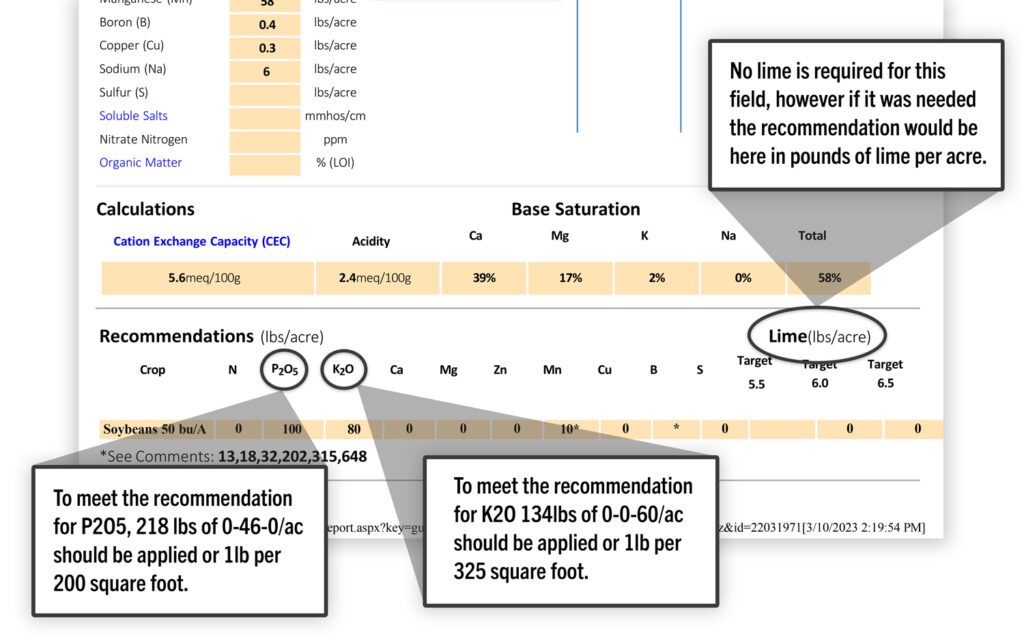

While it’s “buyer beware” for many internet fertilizer sales and by-products, Stancil says any fertilizer purchase and application should be informed by a soil test and report to determine the amount of nutrients in the soil and help home gardeners and farms apply the right amount of fertilizer and lime for optimum growth and cost savings through precise application.

The Clemson University Extension Service recommends soil sampling every year and says soil samples can be taken at any time of the year, but it is best to sample the soil a couple months before planting to allow ample time for the lime to react with the soil.

Information on collecting and submitting soil samples can be found at Clemson’s Home & Garden Information Center or by visiting the local Clemson Extension County Office.

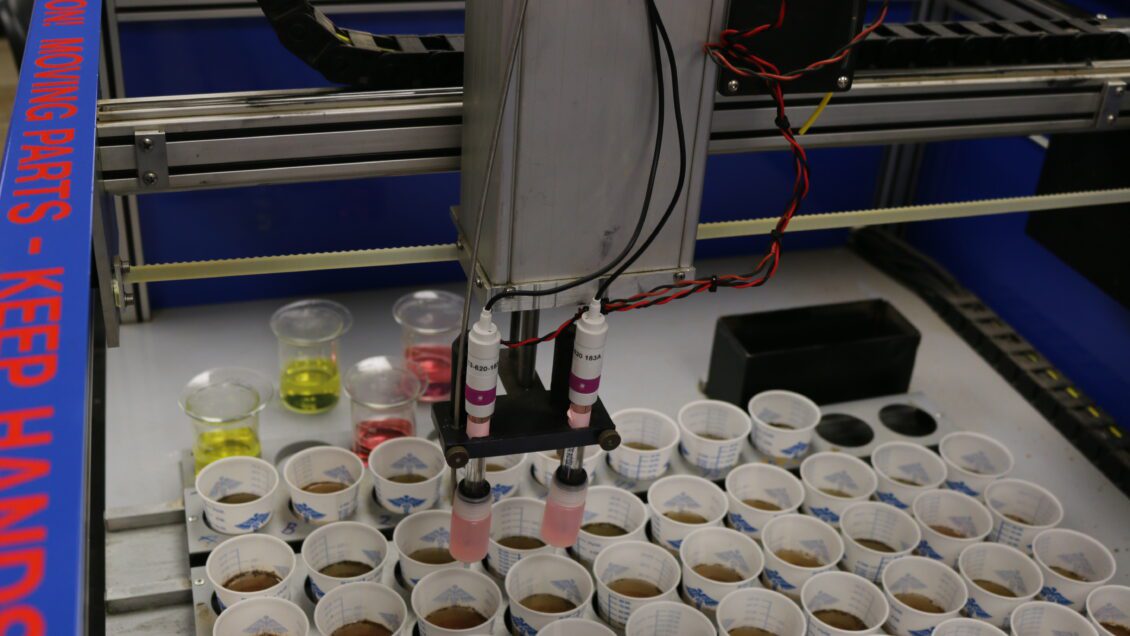

Samples can be mailed directly to the Clemson Agricultural Service Laboratory.

The consumer should receive a soil report in seven to 14 business days. Consumers can then call the Department of Fertilizer Regulation or their local Extension Office if they need help interpreting the report.

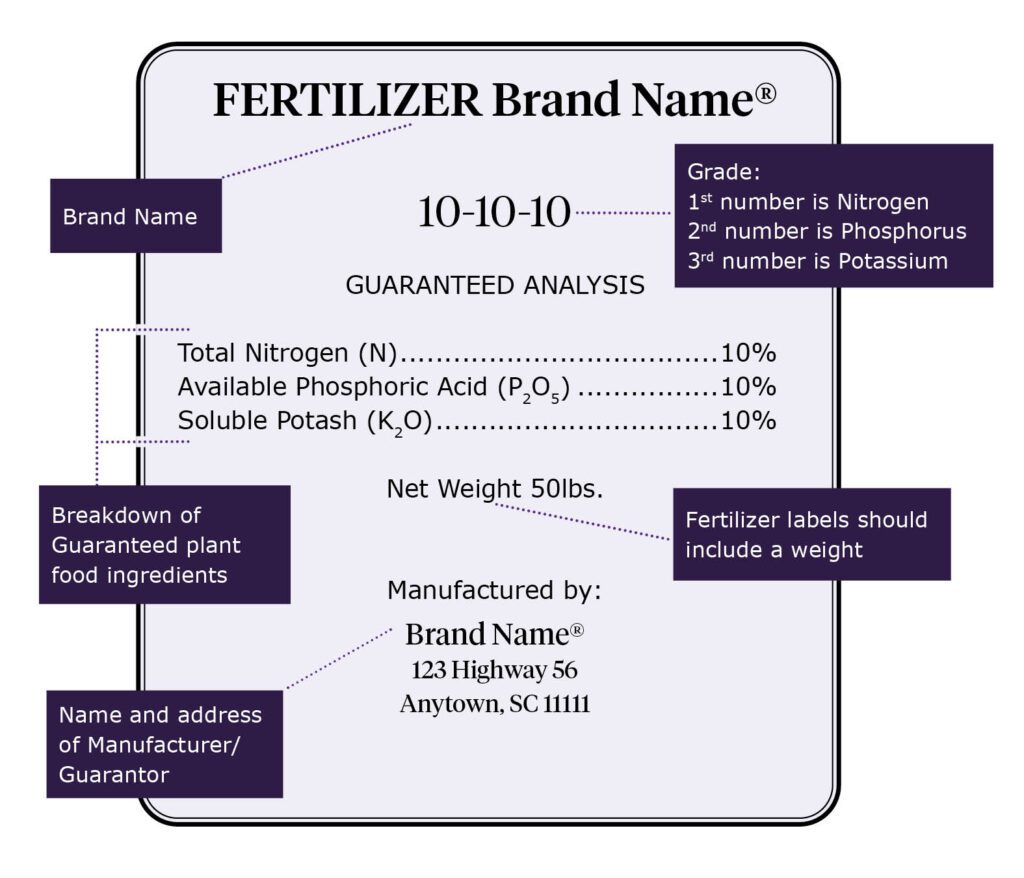

Stancil also says that it’s essential for consumers to understand how to read a fertilizer label. According to law, all fertilizer labels must contain:

- Fertilizer brand name

- Grade, with a number for nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium

- Guaranteed analysis with a breakdown of the guaranteed plant food ingredients

- Net weight

- Name and address of manufacturer

“Those five things need to be on whatever piece of paper you get. So, if you get an invoice, those things need to be on that invoice as well,” Stancil said.

Calculators and web apps developed by the Clemson Extension Precision Agriculture team also can help growers make proper management decisions and develop prescription plans for their crops.

Get in touch and we will connect you with the author or another expert.

Or email us at news@clemson.edu