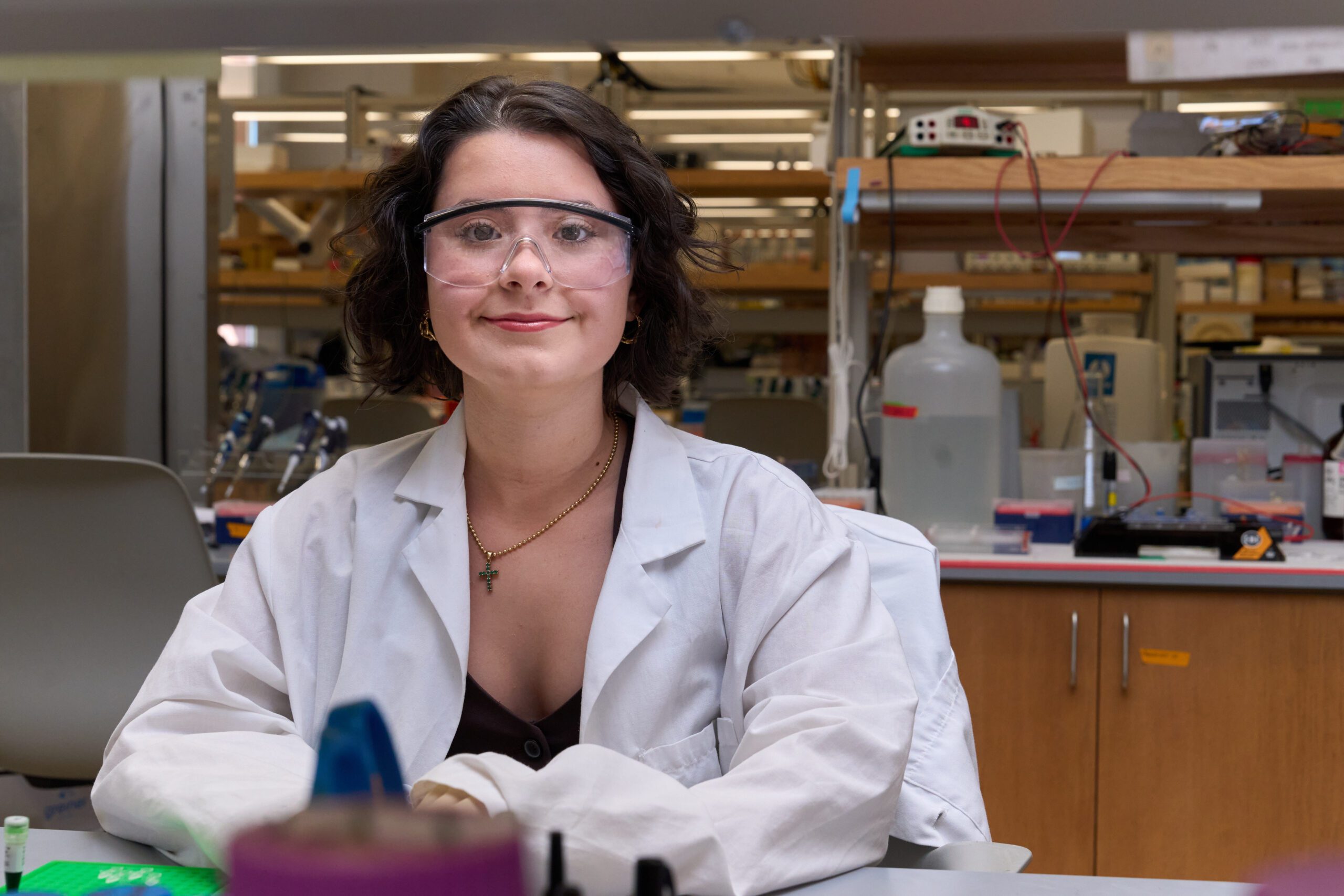

Sofia Willey had her first of five hip surgeries, among them a complete reconstruction, when she was 15.

Doctors thought her problems stemmed from wear and tear from gymnastics, a sport she began at 4 years old. While in middle school, Willey started having abnormally intense joint pain, something doctors attributed to the rigor of competitive gymnastics and her 20 hour-a-week training schedule. It led to constant bouts in and out of physical therapy.

Willey was diagnosed with hip dysplasia, but that did not account for all her symptoms.

Adding together her hypermobility symptoms, scarring and low bone growth, the doctor who performed her hip reconstruction suggested she might have Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS), specifically the hypermobile subtype. EDS is a rare genetic disorder that affects the connective tissue and can cause weak joints. It affects 1 in 5,000 people.

She finally received an official diagnosis five years after that first surgery.

“I didn’t understand what was happening to me, and no one around me did either.”

Willey said her peers and adults sometimes don’t believe she can’t do more strenuous everyday activities. She started using a cane last summer, which acts as a visual cue of her limitations.

Most doctors also do not know much about EDS, she said. “It becomes a lot of explaining your own problems to your doctor so they can prescribe or help you find what you need.”

Limited knowledge

Doctors’ limited knowledge of the disorder is due in part to the EDS’ being under-researched, which has inspired Willey to pursue a degree in genetics and focus on research while in college. She spent this past summer researching her disorder at the Medical University of South Carolina in the lab of Russell Norris, a professor in the Department of Regenerative Medicine and Cell Biology. Norris’s lab is one of the preeminent labs researching EDS, so it had been on Willey’s radar. When Willey saw this internship opportunity for the summer she applied and interviewed for the position.

Willey’s research focused on changes in the immune system of patients with EDS compared to those without the disease. She found a few significant proteins that had different levels in subjects with EDS than in those without.

Diagnostic tool

This research aims at finding a diagnostic tool that could use specific protein levels in the blood to determine if a patient has EDS.

EDS patients are also susceptible to infections due to a weakened immune system. Willey’s work could also contribute to possible treatments to help boost EDS patients’ immunity.

Willey said her time in the Norris lab, which also included patient education, has helped her better understand her disease and problems in her own body. Willey spent time explaining EDS and EDS research to patients in the area, including making packets for recently diagnosed patients and their parents. High schoolers also shadowed in the lab to learn about physically accessible options in STEM.

After graduating from Clemson, Willey plans to attend medical school and specialize in pediatric medicine because she believes complex medical cases are often overlooked in children.

Long wait

After her surgeon suspected she had EDS, she had to wait two years for an appointment with specialists who could officially diagnose her. She started having joint pain at 14 and received an official diagnosis at 20.

But six years is quick when it comes to an EDS diagnosis. Most patients wait an average of 14 years after symptom onset to be diagnosed. That wait is why Willey wants to continue her research and advocacy for this disease.

“When I first started this process, I couldn’t find any information on what was wrong with me. So, the ability to actually get to help other people, maybe have a shorter time being diagnosed, was a big plus for me,” Willey said.

She hopes to change patients’ lives through knowledge of under-recognized diseases. Willey’s expertise would help her diagnose patients more quickly so they can receive needed treatment.

In addition to her research, Willey is a member of the Kappa Delta sorority, vice president of Alpha Epsilon Delta, a national health pre-professional health society, volunteers for Tigers4Accesibility and conducts research at Clemson in Michael Sehorn’s DNA repair and Meiotic Homologous Recombination lab.