It seems improbable that something as rigid as a tree could be turned into a pliable foam that can pad the soles of shoes and cushion seats in cars, but Clemson University researchers have done exactly that.

A research team in the Department of Automotive Engineering used lignin, a wood-processing waste product, to develop a new way of making polyurethane foam without toxic chemicals.

Multiple companies have expressed an interest in the team’s foam, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has recognized it with the 2021 Green Chemistry Challenge Award.

The leader of the research group that won the award is Srikanth Pilla, the Jenkins Endowed Professor of Automotive Engineering and founding director of the Clemson Composites Center.

The team calls its invention nonisocyanate polyurethane (NIPU) foam because no isocyanates are used to make it. Isocyanates are a type of chemical widely used in the manufacture of traditional polyurethane foams.

Exposure to isocyanates can lead to eye irritation, nasal congestion, dry or sore throat, cold-like symptoms, cough, shortness of breath, wheezing and severe asthma attacks, according to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

Pilla said James Sternberg’s chemistry background has been crucial in developing NIPU foam. Sternberg, now a senior scientist in Pilla’s lab, started the research as part of his dissertation after leaving a job as a high school chemistry teacher about four years ago to pursue a Ph.D. under Pilla.

“The core advantage of NIPU foam is replacing the really toxic part of making polyurethanes,” Sternberg said. “When you see someone spraying foam insulation in your house or spraying a polyurethane coating on something, they are in full PPE. One of those components that they are spraying is really bad for you, really toxic.”

Pilla said that when Sternberg started his Ph.D. program, the team had no idea it would end up with the foam it did.

“The goal was to create a polyurethane foam using lignin but using an approach that is different to what others have done and yet make it the most sustainable and 100% biobased as tested by radiocarbon analysis,” Pilla said. “The outcome is what won this award. It’s truly remarkable green chemistry to make NIPU foams.”

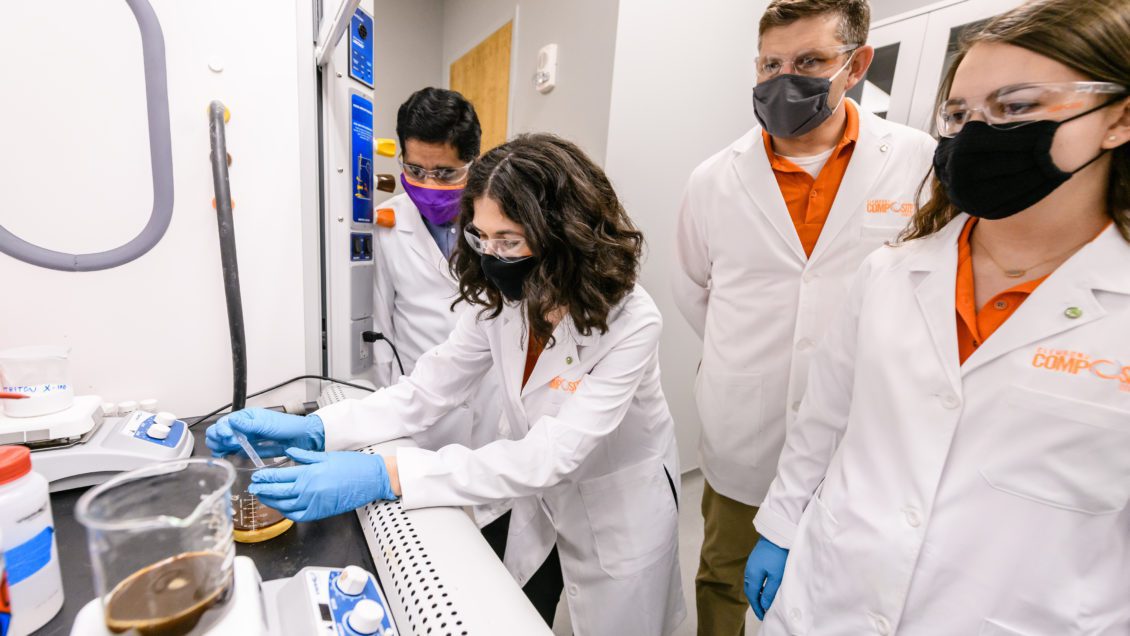

To develop the foams, Pilla and his team have been working in their lab at the Clemson Composites Center in Greenville.

Lignin arrives as a brown powder that looks similar to cocoa powder. The powder is dissolved in carbonate and then precipitated with acidified water, leaving a cake of lignin. The lignin cake is dissolved in another carbonate.

“It creates a little ring on each one of the lignin molecules, and that ring is what we can cure to make polyurethane foam,” Sternberg said.

Researchers leave the lignin out to dry, and it goes back to looking powdery. They form cup-shaped molds out of aluminum foil. In the molds, researchers mix the lignin with a vegetable-oil based curing agent, a solvent, a catalyst and a foaming agent that makes it bubble and rise up.

“It happens really quickly,” Sternberg said. “You’ve got to get it all together and then take the stir bar out and put it in the oven. There is a little bit of an art to it.”

The lignin mixture stays in the oven for about 12 hours at 150 degrees. In the end, the researchers end up with a NIPU foam disk about the size of a silver dollar.

The whole process from powder to disk takes about three days.

“The true innovation of this chemistry lies in the formation of reactive precursors using non-toxic and 100% biobased reagents,” according to the EPA. “In the past, lignin has been made into a reactive precursor using oxypropylation with propylene oxide and added diisocyanates to mimic the synthesis of conventional polyurethane foams. With the lignin-based NIPU foams, the curing agent is derived from environmentally friendly vegetable oils”

Pilla credited the students in his lab for the breakthrough in making NIPU foam.

“People talk about Srikanth getting this award or this grant, but it’s basically these people’s work that gets us to where we are,” he said. They are the pillars of my success.”

Among those students is Olivia Sequerth, who first started working on NIPU foam when she was an undergraduate majoring in materials science and engineering. After graduating, she went on to get her master’s degree and became a research technologist in Pilla’s lab, allowing her to continue the research.

“It’s crazy seeing how far we’ve come,” she said. “I like seeing that whole process, making something from start to finish.”

Green Chemistry Challenge awards “recognize chemical technologies that incorporate the principles of green chemistry into chemical design, manufacture, and use,” according to the EPA. The Pilla team’s award was in the academic category.

Zoran Filipi, chair of the Department of Automotive Engineering, offered his congratulations.

“This award is a reflection of the team’s vision, hard work and unwavering mission to develop a new chemistry technology that improves human health and creates a more sustainable environment,” Filipi said. “This is a well-deserved honor for Dr. Pilla and his team.”

Researchers said several companies have expressed an interest in NIPU foam.

“Everyone wants this to work,” Sternberg said. “They’ve told us, ‘This is great. We believe in it, but you have to show us how it can work for our application.’”

And that is what Pilla’s team is working on now.

Get in touch and we will connect you with the author or another expert.

Or email us at news@clemson.edu