As a trained school psychologist, Lakia Johnson-Drayton knows that educators can have difficulty identifying factors that influence student behavior, especially those students with a disability. Johnson-Drayton serves as assistant director for the Department of Exceptional Children in the Charleston County School District, and she has spent years addressing those behaviors and supporting educators and other professionals who work with students every day.

Educators often consider behavior a choice, when students might “act out” because they don’t have the tools to communicate or regulate their emotions. It’s one thing to address these behaviors successfully on a case-by-case basis, but Johnson-Drayton said it’s an entirely different level of challenge to create supports that do this for an entire school district, especially one the size of Charleston. She and the district had seen success, but she and other leaders knew they could do more to address behavioral issues more efficiently.

“If all you are doing is reacting to those behaviors as an educator or as a school, you aren’t getting at the root of the issue or being proactive,” Johnson-Drayton said. “Organizations need a clear pathway and a game plan to see what they’re doing correctly and where they can improve.”

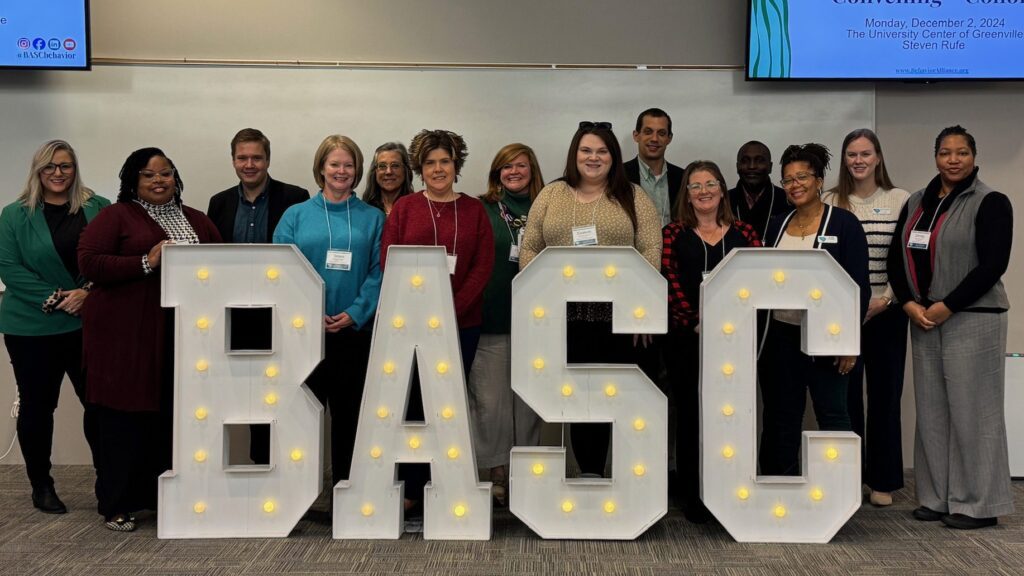

State leadership directed Johnson-Drayton to a group of researchers from Clemson University to turn reactive into proactive. The researchers behind the Behavior Alliance of South Carolina (BASC) have provided pathways to success and support for lasting change in school systems since forming in Fall 2022. The South Carolina Department of Education Office of Special Education Services funds BASC at Clemson University to work directly with the state to help districts and schools across South Carolina build capacity for supporting students with behavioral needs.

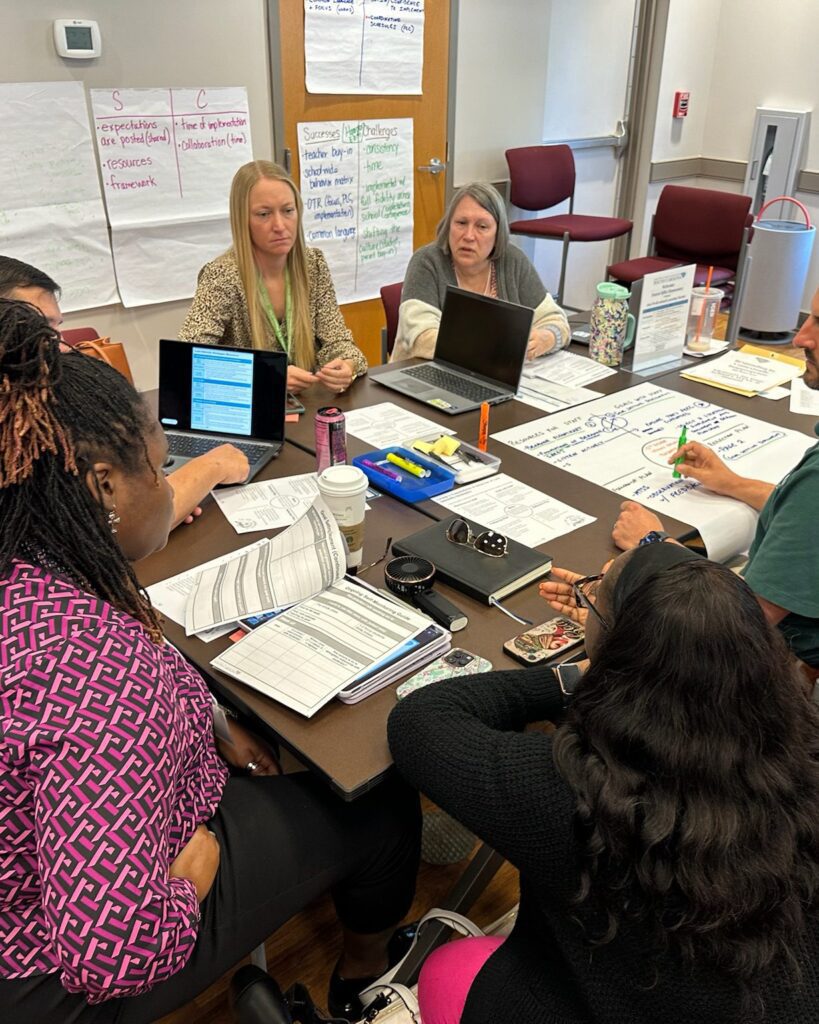

The BASC starts by guiding districts in collecting and analyzing data to define school needs before providing professional development and support in implementing multi-tiered systems of support, a collaborative, evidence-based approach that offers proactive support to all students. Johnson-Drayton said this support places the responsibility on an entire system instead of one person, and she quickly saw the benefits throughout the district.

“Working with BASC has really allowed our whole team to become more in sync,” Johnson-Drayton said. “Shared ownership makes the work doable and prevents burnout, and it was refreshing to be given a roadmap that spells out what tools we have, what we need, what we should do differently and what we’re already doing well.”

BASC currently partners with 18 school districts across South Carolina. Four schools in the Charleston County School District are actively implementing or preparing to implement schoolwide behavior systems, but there are more than 40 more across the state that are actively involved. According to Megan Carpenter, project lead for BASC, the current work focuses on universal supports for schools, such as the type being implemented in Charleston County, while plans are in place to include more support for targeted and intensive supports.

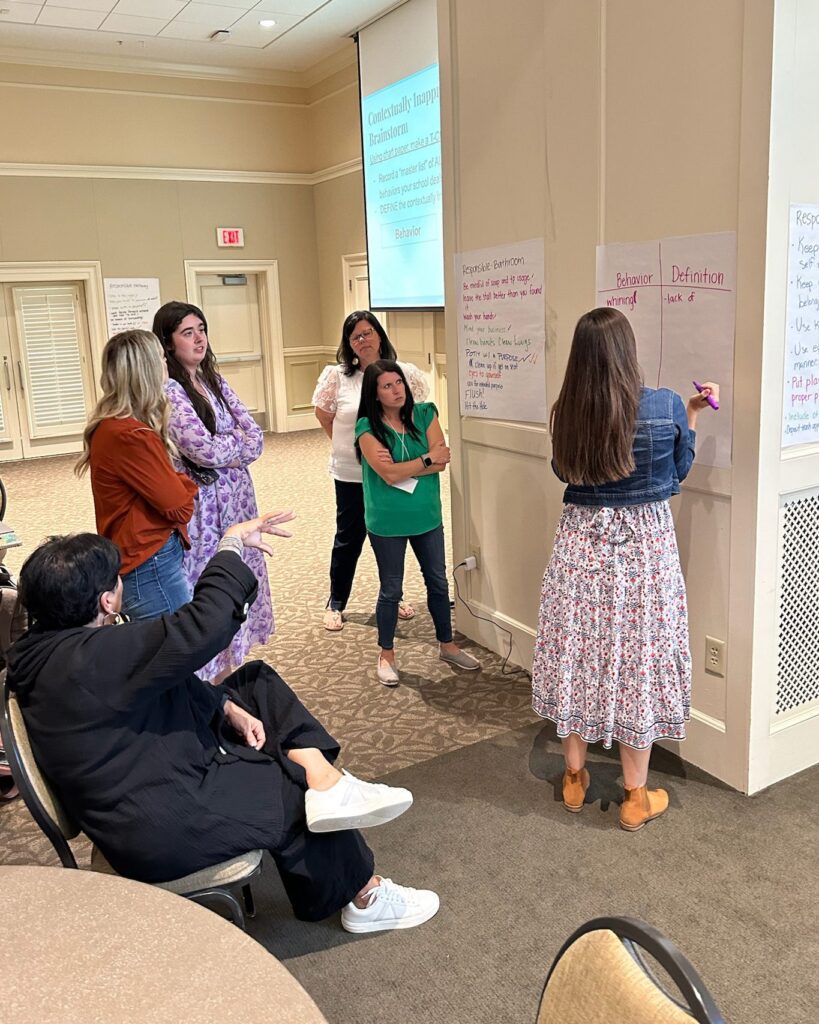

Carpenter said the focus of BASC has shifted from one-off trainings to building long-term district capacity. The entire goal is not to be needed at all; as district leaders take over the work, researchers designed BASC to phase out. Carpenter feels that BASC’s work alongside districts to build capacity has led to more districts taking notice and requesting partnerships.

“That growing recognition is evidence that what we’re doing is working,” Carpenter said. “Teachers are applying new practices while other districts are developing launch plans for our tier one supports.”

Support data shows that a proven method is only growing in use. Regarding district-level support, BASC partnerships have impacted more than 200,000 students across 18 districts, with more than 1,400 hours of in-person learning and nearly 300 hours of virtual learning. Survey data of participants shows that 100% of respondents agreed that professional development provided by BASC has impacted their work.

Carpenter said that the project’s use of Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) has helped to cement professional learning for district educators and staff. Originally designed to educate and train laboratory and health care professionals on diagnostic excellence, the BASC team has applied ECHO principles to increase the knowledge and workforce capacity through distance-based professional development. ECHO provides virtual follow-up to in-person learning and has helped to foster a community of practice among and across district teams.

Carpenter said it is rewarding to help equip entire districts and schools with the tools to cascade knowledge to individual educators on addressing specific behaviors. When common issues cited by teachers leaving the profession across grade levels are discipline and student behavior, she sees it as vital work to get teachers out of “survival mode” in classrooms.

“When you get to those one-on-one, teacher-student interactions, it’s often about responding and not reacting,” Carpenter said. “We want to make that response automatic, preventative of future behaviors and part of a school’s foundation for addressing behavior.”

BASC currently has two more years of confirmed funding and strong state-level support, and the project is currently exploring additional funding sources for a potential third cohort to expand its impact further. Carpenter is tracking the cohorts’ implementation results to prepare reports on effectiveness.

Johnson-Drayton’s work will be a part of those results, as she is currently engaged in implementing multi-tiered systems of support in Charleston. But beyond that, she is also involved in train-the-trainer activities to build internal district capacity. She has been continually impressed that the work of BASC doesn’t feel like another thing to “add to the plate” or yet another initiative to take on.

“I would say everyone’s biggest obstacles are time and competing priorities, so when I say this work doesn’t feel like just ‘another thing,’ that’s a big deal; it’s folded in as seamlessly as possible through virtual sessions and integrating training into time already reserved for professional learning,” Johnson-Drayton said. “BASC works collaboratively and not prescriptively, and we are happy they are helping us develop a sustainable system.”