While shoppers fight for deals in stores and online on Black Friday, we’re taking a moment to celebrate another galactic holiday, Black Hole Friday.

Jonathan Zrake, an assistant professor in the Clemson University Department of Physics and Astronomy, shares five fun facts about black holes, one of the most mysterious objects in the universe.

Closest black hole?

The closest known black hole to Earth is about 1,560 light-years away in the constellation Ophiuchus. It was discovered in 2022 and is a dormant stellar-mass black hole, meaning it’s not actively consuming nearby material. “It’s not likely that astronauts will ever be able to travel even to the nearest black holes,” Zrake said.

The Milky Way Galaxy, like most galaxies of similar size, has a supermassive black hole at its center. Ours is called Sagittarius A*, and it’s at least four million times the mass of the sun and 26,000 light-years away.

Two types of black holes

There are two types of black holes: stellar-mass black holes and supermassive black holes.

Stellar-mass black holes form from collapsed dead stars. They are usually between a few and 100 times larger than the mass of the sun. When stars reach the end of their lives, they explode in what’s called a core-collapse supernova, leaving behind about 20-30% of their original mass to form a black hole.

Another type of black hole, called a supermassive black hole, is up to 10 billion times larger than the sun. These black holes are at the center of some of the universe’s largest galaxies.

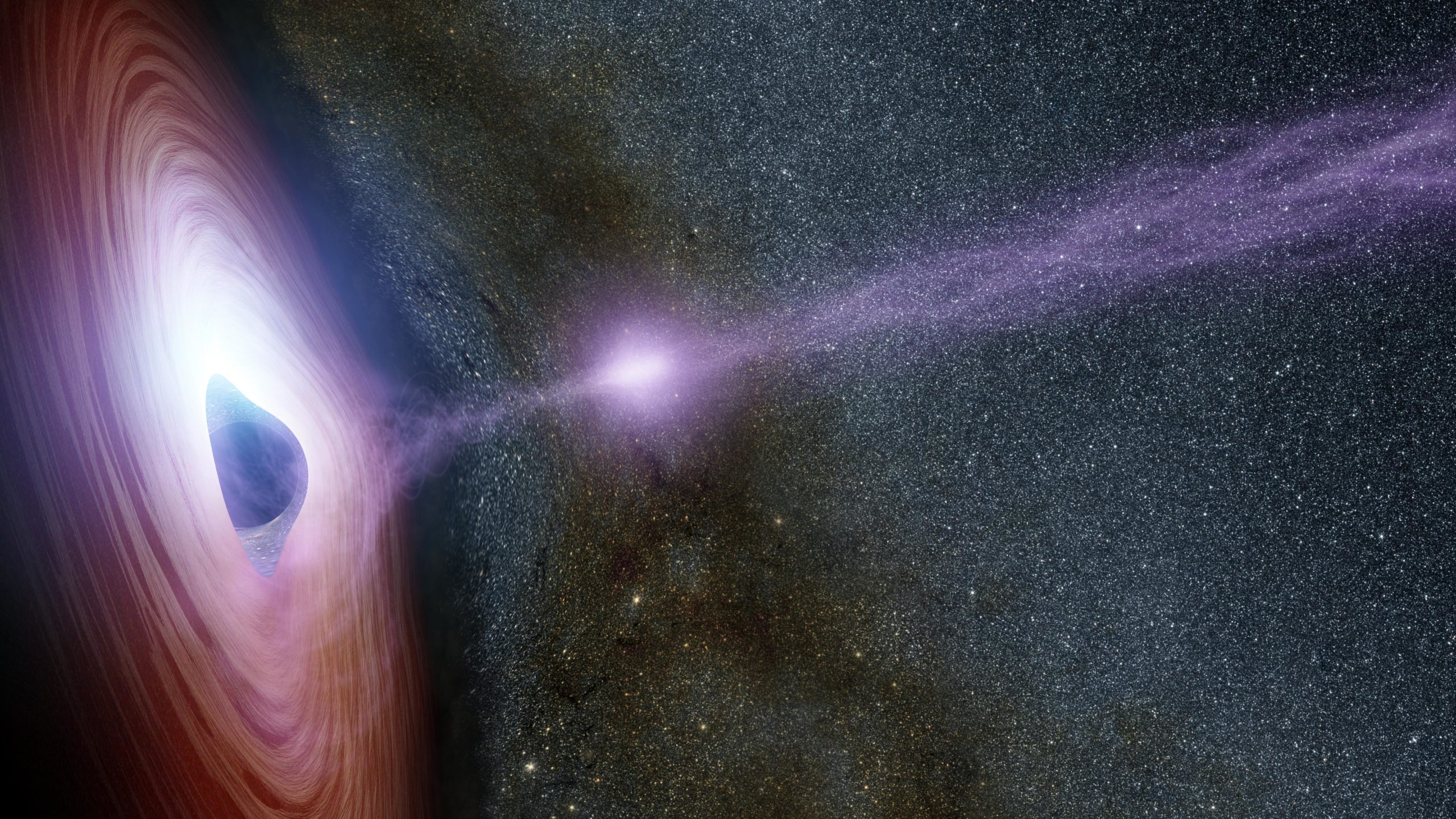

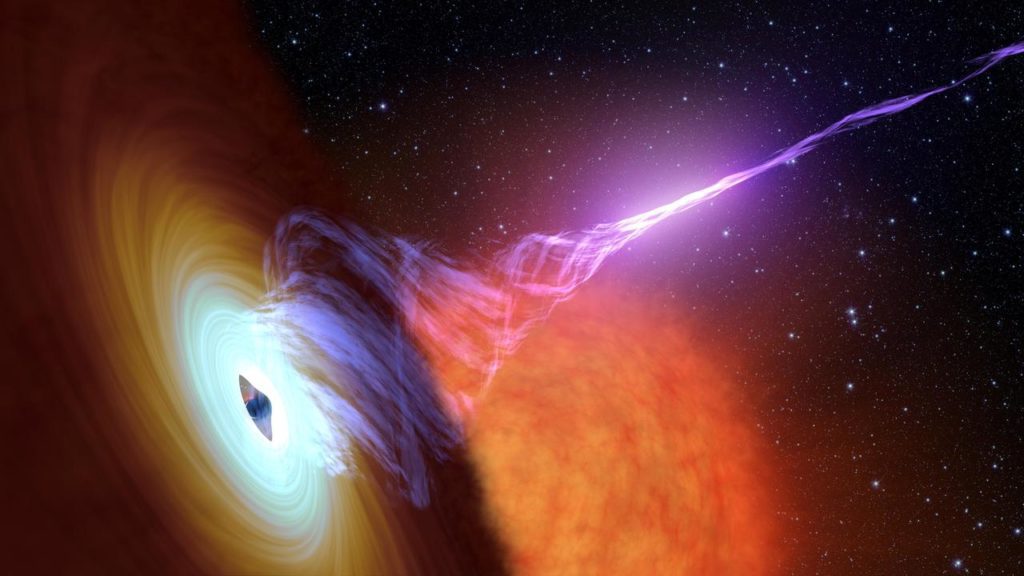

Scientists are unsure about the origin of supermassive black holes. One hypothesis is that they originally formed from the collapse of stars and then continued to grow by consuming other stars, black holes and the gas that exists in galaxies. Gas falls into black holes, causing them to grow larger and attract even more gas. The cycle is regulated by the black hole “vomiting” gas back into the environment.

Another theory, known as the direct collapse theory, describes a massive, self-gravitating cloud of gas that contracts under its own gravity, becoming denser until a black hole forms and continues to grow. Scientists also hypothesize that supermassive black holes formed when the universe was less than a billion years old, relatively early in the universe’s current 13.6 billion-year lifespan.

‘Missing’ black holes

When black holes grow from a lower mass to massive black holes, scientists posit that they must go through intermediate ranges, yet scarce evidence of a “medium-sized” black hole exists.

“It could be that they’re just too dim,” Zrake says.

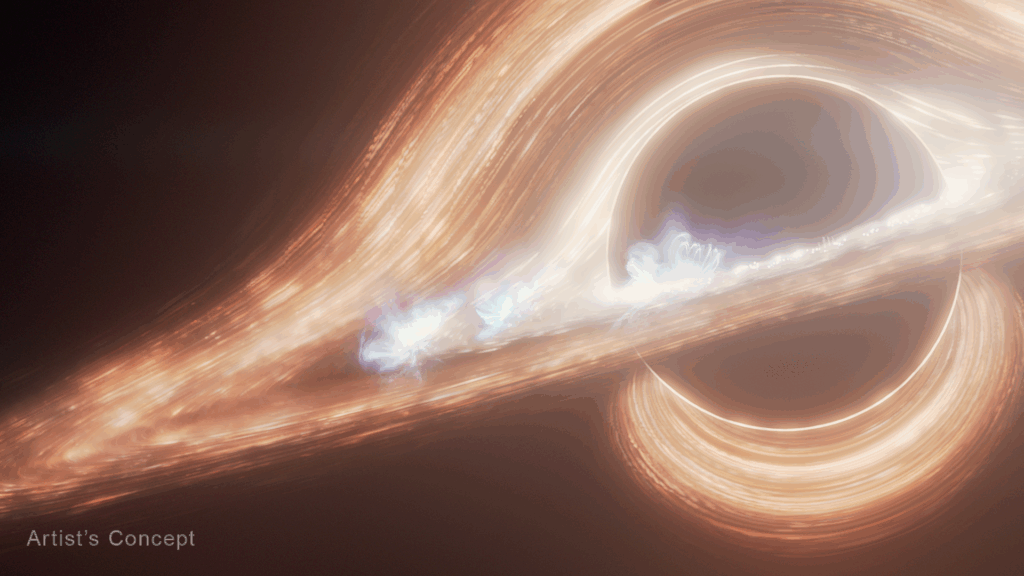

A supermassive black hole is bright because gas glows brightly as it’s about to be consumed. The bigger the black hole, the more gas it attracts, and the brighter it is. Intermediate black holes may not attract enough gas to be visible from a distance. Lower mass black holes, such as the stellar-mass black holes discovered in the Milky Way, are detected only because they participate in a binary system where the black hole is actively consuming a companion star. The star and black hole orbit one another, and gas from the outer layer of the star falls into the black hole, creating a detectable brightness.

How do we detect black holes?

Scientists utilize both ground-based and space-based telescopes to make observations about black holes in our galaxy and beyond. They use a variety of telescopes, including optical and radio, as well as X-ray and gamma-ray telescopes, which are located only in space.

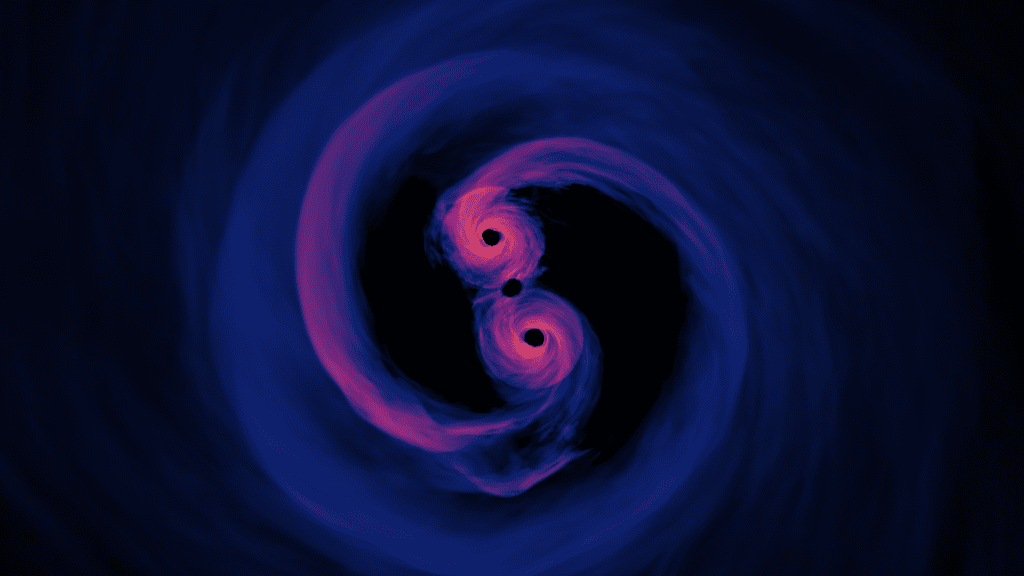

A new type of tool detects gravitational waves, which travel at the speed of light but are rippled into the fabric of time, up to billions of light-years away. These gravitational wave detectors have been developed over the past 50 years. Black holes themselves do not usually produce gravitational waves because they are stationary. But when black holes exist in an orbiting binary system, the motion creates gravitational waves.

There are currently four operational detectors on Earth, located in the United States, Italy, India and Japan. They detect loud bursts of gravitational waves produced when two black holes collide. Scientists are working to put a gravitational wave detector in space, called LISA, to detect binary black hole systems and hopefully find black holes that previous instruments were unable to detect.

Research on black holes

Zrake researches binary systems, studying how scientists might make predictions to discover binary massive black holes.

Scientists know black holes consume other black holes, and to do that, they must be part of a binary system. Still, scientists have had difficulty finding these systems. Zrake studies “signposts” — indirect signatures that reveal the presence of binary black holes — by predicting how they systems interact with the gas around them. Because binary black holes are too distant and compact to image directly, these signposts are essential for guiding astronomers toward the best targets for observation and study.