It’s in the family genes.

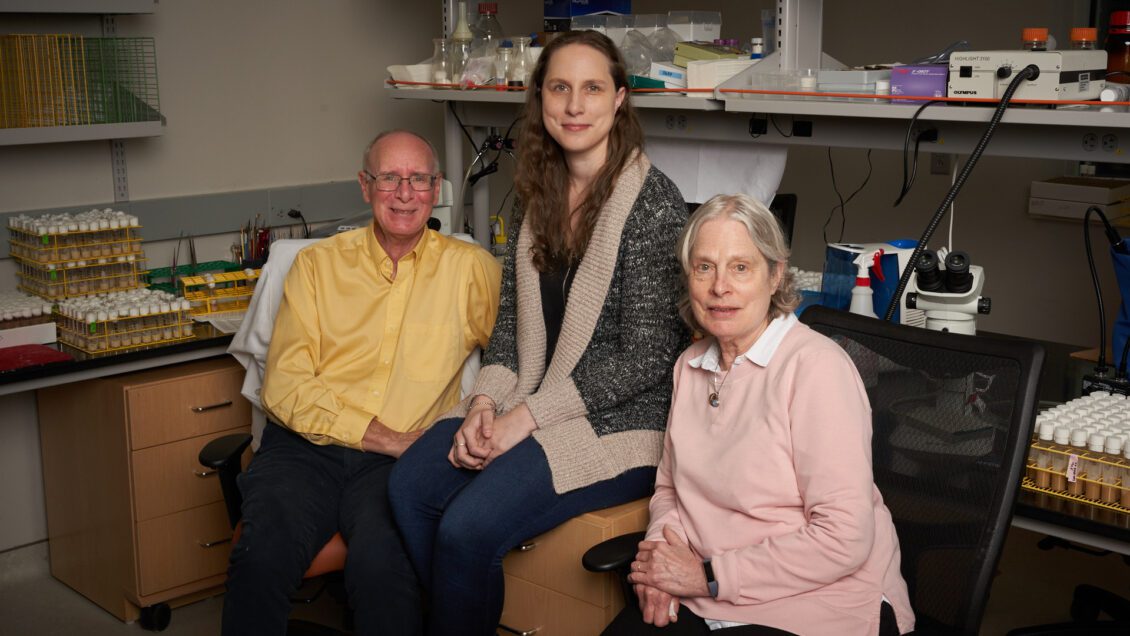

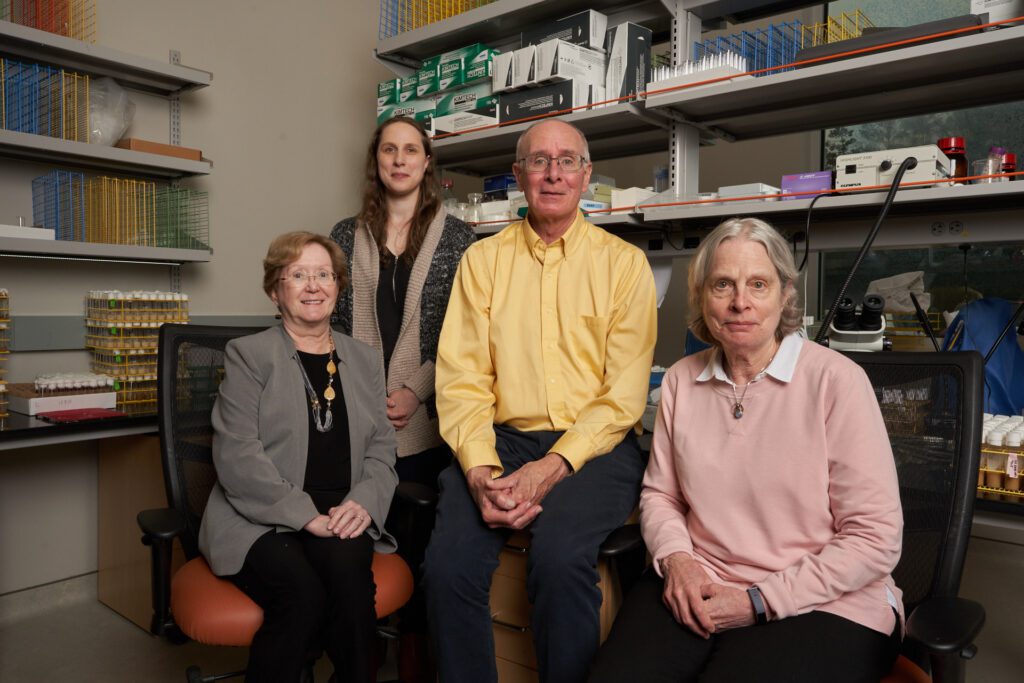

Husband Richard, wife Roberta and daughter Rachel Lyman all work at the Clemson University Center for Human Genetics, where renowned geneticist Trudy Mackay’s lab breeds and studies fruit flies to solve genetic mysteries in humans.

Richard was the first postdoctoral fellow Mackay hired when she was establishing her lab 35 years ago at North Carolina State University. He’s worked for Mackay ever since, advancing to senior research scientist, and played an integral role in the lab’s success.

“Richard has been a driver in pretty much every project we’ve ever done,” Mackay said.

Roberta has managed the labs at the CHG since it opened in Greenwood, South Carolina, in 2018.

“When we first got here, the halls echoed because there were so few people working,” Roberta said. “Now, we’re bursting at the seams.”

The Lymans expected to stay at the CHG for a year, maybe two, until the center was up and running.

“We said, ‘We’ll retire next year.’ A year passed, and we’d say, ‘We’ll retire next year,’” Richard said.

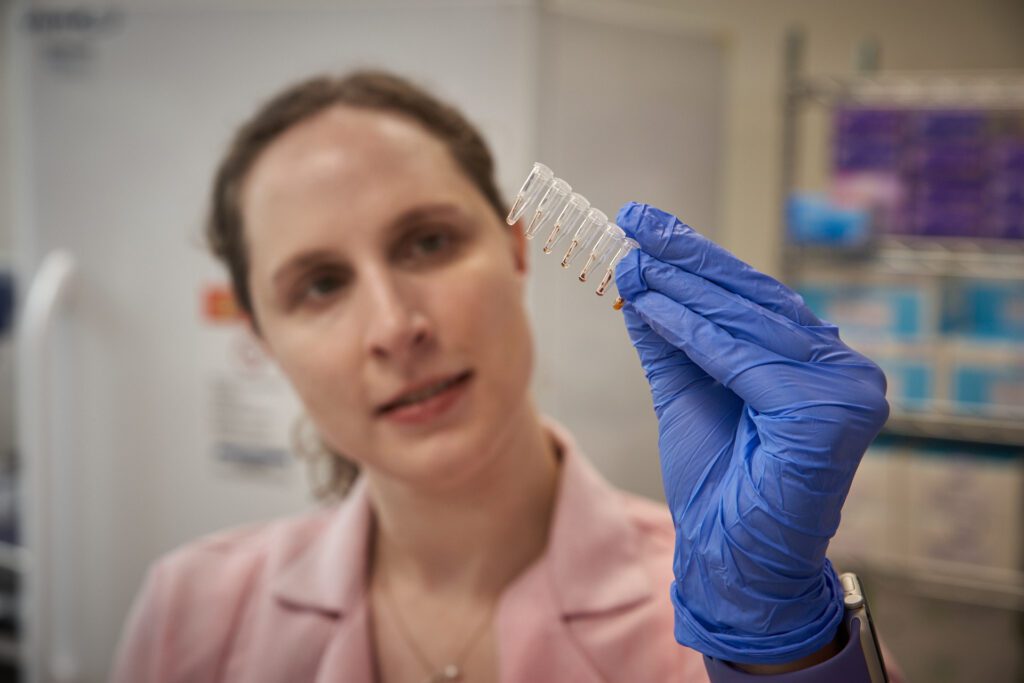

“Next year” has arrived, and Richard and Roberta are retiring on Jan. 30. But there still will be a Lyman in the lab shared by Mackay and husband and fellow scientist Robert Anholt. Rachel, who originally thought she’d pursue a career in dance, is the CHG’s genomics core director. The molecular geneticist was hired shortly after earning her Ph.D. in evolution, ecology and population biology from Washington University in St. Louis, her father’s alma mater. She earned her undergraduate degree from Knox College, her mother’s alma mater.

“Robert always joked that they were going to have to keep my dad here until I got my Ph.D. because they needed a Lyman in the lab. But I never thought I would actually end up here because my Ph.D. was in such a different field. My Ph.D. was on the phylogenetics of rare southeastern North American plants,” she said. “But I love the work I’m doing, and I love working for Trudy.”

She admits that being the only Lyman there will take getting used to.

“Working here without them is a difficult thing for me to process, especially my dad because he’s worked for Trudy for so long. To me, the fly lab is as much his as Trudy’s,” she said. “It will be strange being the only Lyman in the lab, but I’m going to do my best to continue the legacy.”

First meeting

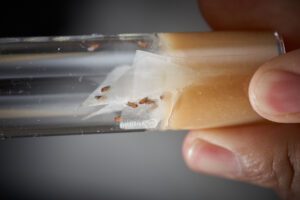

Richard and Roberta met while working in a fruit fly lab at Northern Illinois University. The common fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, is often used in scientific research because they reproduce quickly and about 75 percent of human disease genes have a counterpart in the fly.

A pump that dispensed fruit fly food wasn’t working, and Roberta, who was a bacteriologist but was helping run a couple of fly labs, took it apart. It was spread all over a bench when Richard walked in to tell her they needed to order supplies for the lab in which she’d be working. She asked him if he knew anything about fixing pumps. He said no. “Then you can get out of here,” she said.

Fortunately, he came back.

Richard and Roberta married on Aug. 28, 1988, and spent their honeymoon driving to North Carolina so Richard could start his postdoc work with Mackay at N.C. State just days later. The lab fell under the purview of the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences and its research was designed to be directly applicable to animal and plant breeding systems.

Many of the lab’s projects focused on bristles, sensory structures on the exterior of the fruit fly and a part of its nervous system. As the lab grew, researchers studied additional traits such as lifespan, olfaction (the sense of smell), stress resistance and fly models of human disease.

As computers became more powerful, researchers were able to identify the genes involved in the traits they were studying. That led to questions about how various genes contributed to quantitative traits. One gene they studied caused the fly to secrete a fluid that caused a crusty eye that evolved into fly glaucoma. A homologous gene was found that caused glaucoma in humans. The glaucoma-related studies continued in Mackay’s lab in collaboration with N.C. State’s veterinary college, where Roberta Lyman was a research specialist. The Lymans’ beagle was part of the study.

Trip to the Raleigh Farmers Market

The lab needed fruit flies to use in its research, so Mackay asked Lyman to collect some.

Armed with a net, Richard headed off to the Raleigh Farmers Market during peach season. “If I was really lucky, I’d come by as they were unloading the truck and could sweep my net over as they opened the box and catch the flies as they escaped, which was very productive,” he said. If he wasn’t lucky, he’d look for discards from the previous day.

“Drosophila melanogaster love rotting fruit,” he said.

Rachel, who was in elementary school, would sometimes accompany him, holding the net or carrying the flies that had been collected that morning. “The way he got me to go was to bribe me with free peaches,” she said.

They got their fair share of funny looks, until he explained to the farmers that he was collecting fruit flies to be used in genetic research. Eventually, the vendors started to hide some of their discard bins from the trash collectors so there would be flies for Richard to collect if he was running late.

Richard captured over 1,000 pregnant female fruit flies. He then inbred the flies for 20 generations. The inbreeding virtually eliminated genetic variation in each of the lines. The flies were the start of the Drosophila Genetic Reference Panel, a valuable resource of 200 fly lines with fully sequenced genomes that are distributed for free by the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center to scientists all over the world. During his time at Clemson, Richard expanded this resource to 1600 fly lines.

Blazing her own path

Rachel didn’t plan to follow in her parents’ footsteps despite having grown up around science labs. One of her first memories is going to Mackay’s lab when school was out and curling up with a pillow and quilt under a fly bench while her father worked.

“I had always wanted to do science. I just didn’t think I could,” she said. “I was a sophomore in high school and my chemistry teacher, in front of the whole class, told me I couldn’t be a scientist because I wasn’t anti-social enough.”

Although she kept taking Advanced Placement classes in science, she switched her focus to dance. She planned to apply to dance conservatories, but when she had some health issues and injured her knee her senior year, she reconsidered.

“I suddenly realized that dance is not an easy career, that my entire career would be based solely on my body’s ability to hold itself together for a long time,” she said. “I panicked. I applied to a random set of colleges and had no idea what I was going to do.”

Then her father got her a summer internship in Anholt’s lab. She decided to major in biology and minor in dance studies in college. Each summer, she’d work in Mackay’s lab. After she defended her dissertation and had her Ph.D., Mackay asked if she’d be interested in the genomics core director job at CHG.

Roberta said she’s happy that Rachel is working in the lab and no longer in the field.

When Rachel was doing field work in Mississippi for her Ph.D., a tornado hit her car, although Rachel is quick to point out she was inside the hotel and not outside when it struck.

Richard said he’s happy his daughter has decided to carry on the family tradition.

“It’s neat that there will still be a Lyman in the lab,” he said. “I want her to stay here as long as it makes her happy.”

Get in touch and we will connect you with the author or another expert.

Or email us at news@clemson.edu