The news that lasers are capable of rerouting lightning and could someday be used to protect airports, launchpads and other infrastructure raised a question that has electrified some observers with curiosity:

Just what else can these marvels of focused light do?

We took that question to Clemson University’s John Ballato, one of the world’s leading optical scientists, and his answers might be—you guessed it—shocking.

Some lasers shine more intensely than the sun, while others can make things cold, he said. Lasers can drill the tiniest of holes, defend against missile attacks and help self-driving cars “see” where they are going, Ballato said. Those are just a few examples—and all have been the subject of research at Clemson.

If anyone knows about how light and lasers are used, it’s Ballato, who holds the J.E. Sirrine Endowed Chair of Optical Fiber in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering at Clemson, with joint appointments in electrical engineering and in physics.

He has authored more than 500 technical papers, holds 35 U.S. and international patents and is a fellow in seven professional organizations, including the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Ballato recently returned from San Francisco, where he served as a symposium chair at SPIE’s Photonics West LASE, “the most important laser technologies conference in the field,” according to its website.

“We’ve got a great opportunity to shine a light—pun intended—on Clemson’s leadership in laser technology,” said Ballato, who was not involved in the lightning-related research. “Clemson has some of the world’s top talent in laser technology, unique facilities that include industry-scale capabilities for making some of the world’s most advanced optical fibers and opportunities for hands-on learning. If you want to be a leader, innovator or entrepreneur in lasers, Clemson is the place for you.”

Ballato is among numerous researchers at Clemson who are doing seemingly miraculous things with laser light. Here are five things lasers can do (other than deflect lightening) that Clemson researchers are working with today.

Ballato was part of an international team that developed the first laser self-cooling optical fiber made of silica glass and then turned that innovation into a laser amplifier. Researchers said it is a step toward self-cooling lasers. Such a laser would not need to be cooled externally because it would not heat up in the first place, they said, and it would produce exceptionally pure and stable frequencies. The work was led by researchers at Stanford University and originally reported in the journal Optics Letters.

The light from lasers can be made to twist or spin as it travels from one point to another. This can be done by engineering the light’s “orbital angular momentum” and is central to research led by Eric Johnson, the PalmettoNet Endowed Chair in Optoelectronics, with help from several other researchers, including Joe Watkins, director of General Engineering. The technology could make it possible to channel through fog, murky water and thermal turbulence, potentially leading to new ways of communicating and gathering data.

Some lasers are orders of magnitude more intense than the surface of the sun, thanks to specially designed optical fiber that confines that light to a fraction of the width of a human hair. These powerful laser devices can be used to shoot missiles out of the sky or to cut, drill, weld and mark a variety of materials in ways that conventional tools cannot. Lasers, for example, are used to cut Gorilla Glass on smartphones. Clemson researchers helping advance laser technology in this direction include: Ballato; Liang Dong, a professor of electrical and computer engineering; and Wade Hawkins, a research assistant professor of materials science and engineering.

Lidar, which stands for Light Detection and Ranging, is a technology that employs pulsing laser beams to measure distance to objects or surfaces. For self-driving cars, lidar serves as the “eyes” that help vehicles navigate the streets. Lidar can also be used for mapping and surveying and measuring density, temperature, and other properties of the atmosphere. The technology has been employed in numerous projects at Clemson, including Deep Orange 12, an autonomous race car designed by automotive engineering graduate students.

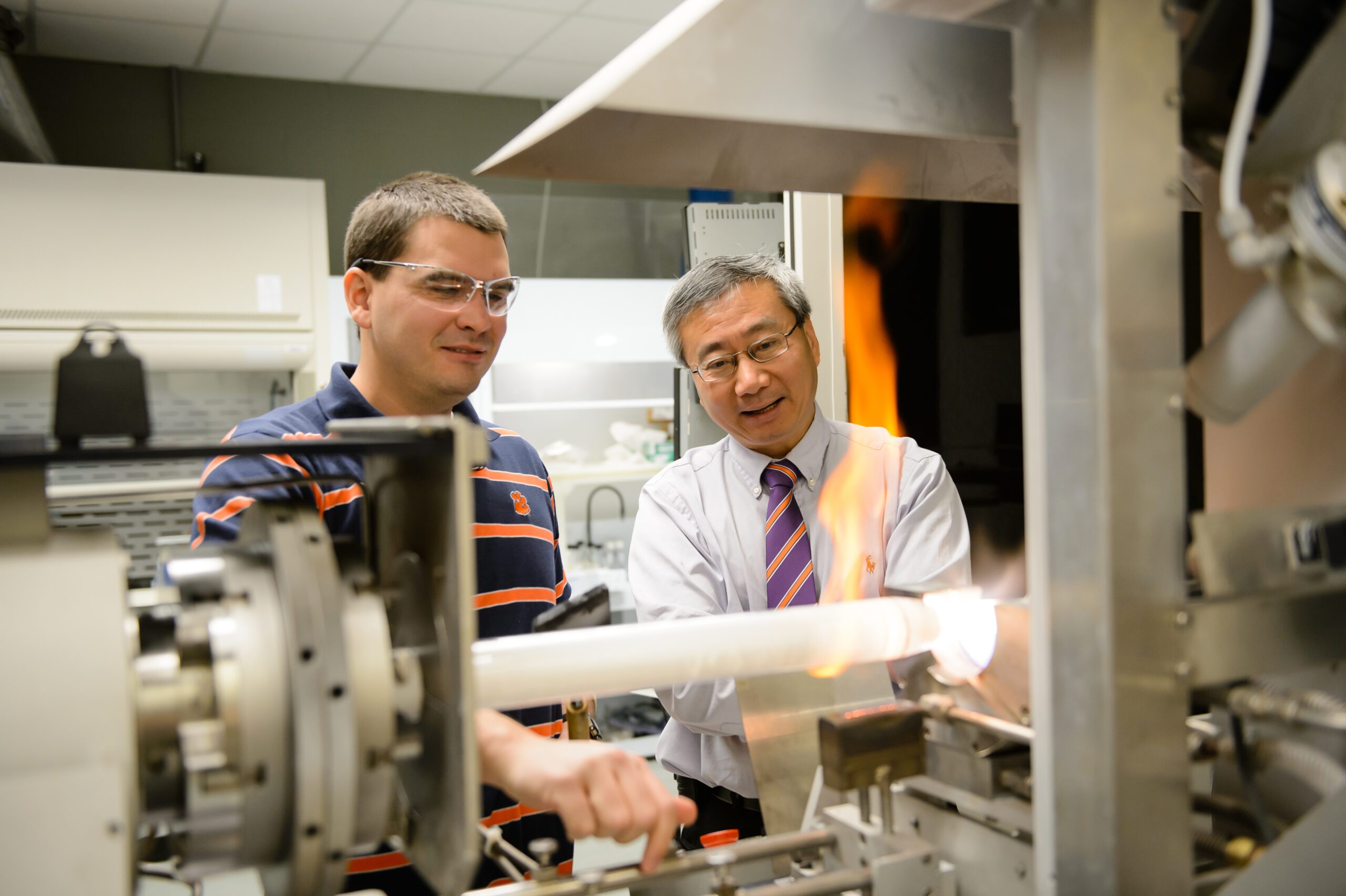

Lasers are also playing a role in helping develop clean energy sources. One of the major challenges in creating hydrogen-powered turbines is protecting the blades against heat and high-velocity steam so extreme it would vaporize many materials. A possible solution under study at Clemson would be to cover turbine blades with a special slurry and use a laser to sinter it one point at a time, creating a protective coating. The research is led by Fei Peng, an associate professor of materials science and engineering.

Get in touch and we will connect you with the author or another expert.

Or email us at news@clemson.edu