Women influence more than 80 percent of all new car purchases, yet they make up only a little over one-quarter of the automotive industry’s workforce. For the women of Deep Orange — Clemson’s flagship vehicle prototyping program – data points like these drive them to want to make an impact in their chosen field of automotive engineering. Learn how three women are bucking this trend by leading their colleagues, championing women’s perspectives and needs in automotive design and why they hope sharing their experience can encourage other young women to pursue careers in engineering.

Rivkah Saldanha was nervous.

As one of four women in her undergraduate engineering class, she knew how to operate as the only woman in the room. But as a graduate student at Clemson applying to build a vehicle prototype with a global automotive company, it felt different. She had just submitted her application with something she had never said before: she wanted to lead the team.

“It felt like a big ask,” she remembers. “I doubted myself and thought, ‘Should I apply for this role, or should I wait for one of my professors to say, ‘Rivkah can do it’?'”

Years after that pivotal moment, Rivkah spends her days at General Motors’s Milford Proving Grounds, developing some of the world’s most powerful cars: high-performance Cadillacs. It’s an incredible feeling to see your work — the 2022 CT4-V Blackwing or Celestiq EV, for example — on the road, she says. “I can’t wait to see these vehicles in the hands of consumers.”

Though Rivkah’s love of cars started long before her time at Clemson, the skills and experience she earned through the Deep Orange vehicle prototype program were crucial to building her confidence as a leader and an engineer, she says. Through Deep Orange, graduate students work as a team to develop and build a one-of-a-kind concept car over two years — a test not only of expertise, but leadership, project management and pure grit.

“As women, before we say we can do something, we want to prove we can do it. We question ourselves before we even give it a shot.”

RIVKAH SALDANHA, DEEP ORANGE 5 | GENERAL MOTORS

And she’s not alone. Women take the same classes, ace the same tests and earn the same GPAs as their male counterparts, yet they are far less likely to choose STEM fields over others and experience significantly higher attrition rates if they do. Men are 2.4 times more likely to work in STEM fields, and only 6.7 percent of women graduate college with a STEM degree, according to Microsoft.

At Clemson, programs such as Deep Orange aim to change that by developing students via hands-on engineering experience. Now in its 13th year, the program draws more and more women from around the world to learn, grow and succeed in automotive engineering. The ExxonMobil-sponsored Deep Orange 11 team boasts women in all levels of leadership. Deep Orange 12 — an autonomous Indy racecar sponsored by EY — relies heavily on women for pivotal roles in programming and structures.

“There’s nowhere else, even in industry, you can learn that much in such a short amount of time and have all of this knowledge you can apply later,” says Rivkah, who led her team of 16 male students to unveil their vehicle in Detroit in 2015. “Things in the real world feel easier once you’ve gone through Deep Orange.”

Lead by doing

The history of Deep Orange – Clemson’s flagship vehicle prototyping program – is full of brilliant women such as Rivkah. Through the program, automotive engineering students complement their graduate studies by developing, engineering and building a one-of-a-kind concept vehicle.

“Having an engineering project that MS students get to work on the entire time they are in grad school is really unique,” says Dr. Johnell Brooks, who has helped mentor students in Deep Orange since its inception. “For the students, the Deep Orange program is about developing and building a vehicle, but what is more important than building each vehicle, is developing the skills of our students so they are prepared for the automotive industry.”

Working hand in hand with industry, each cohort’s goal is to engineer their vehicle to solve a grand challenge. Over the years, students have designed vehicles for a multitude of consumer groups, use cases and environments, balancing their innovations with environmental, social and economic factors faced by OEMs today.

“It is fantastic to see the students’ skills and confidence develop throughout the Deep Orange program. For many years I have been the only female in our department – it is important to me to serve as a mentor for all of the students, but especially our female students,” says Brooks. “The relationships that have developed during Deep Orange are like those of a family and last long after graduation.”

In industry, engineering a vehicle can take up to five years from start to finish including functions such as supply chain management, distribution and safety testing, among others. Deep Orange students don’t aim to mass produce their creation, but rather learn to make decisions based on real-life constraints of budgets, competing priorities, deadlines and even parts availability.

Another real-world element is multiple design reviews where the students present the project’s status to sponsors and stakeholders.

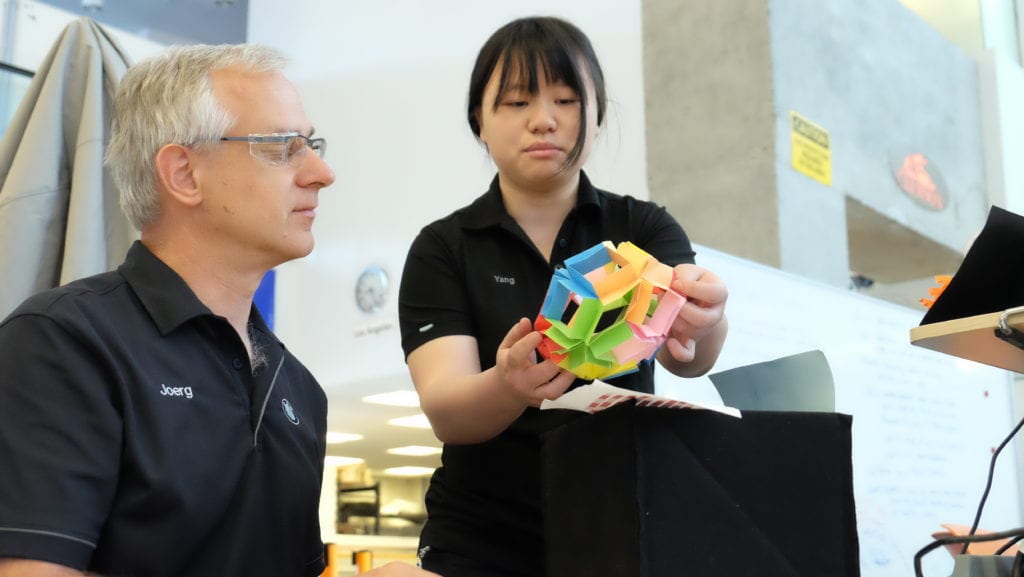

Presenting to high-level executives and experienced engineers was nerve wracking but ultimately excellent practice for the real world, says Yang Yang, the interiors subsystem lead for BMW-sponsored Deep Orange 7 project.

“Meeting with people in such high roles was stressful every time, but it really built my confidence to say what I needed to say in front of all of those people,” says Yang. “As a team, we had to cooperate and solve problems and sometimes even argue about priorities. I learned how to work in a team, when to be humble and when to speak out.”

Today, Yang uses those skills and bolstered confidence as an occupant package engineer at Ford Motor Co., a role very similar to what she did on her Deep Orange team. Her work can be found on nearly every production vehicle Ford manufactures in attributes such as driver visibility, seating position, ingress and egress, among others. While these are the basic requirements needed in any vehicle, getting them wrong could put passengers in danger or cause customers to feel uncomfortable in the vehicle.

Diverse teams for better outcomes

Attributes like ingress and egress fall under the umbrella of human factors, a crucial component of automotive design and a common theme across the program’s last 12 student teams. At Clemson, Dr. Brooks takes the lead to help students understand and apply one of the most important concepts for aspiring automotive engineers: Who is your customer and what do they actually need?

“While excellent engineering is required in all of today’s vehicles, if a potential customer is not comfortable, they likely won’t buy it,” says Brooks. “As human factors psychologists, we study individuals’ capabilities and limitations, we understand the variety of needs of different types of consumers.”

Rivkah and her teammates traveled from dealership to dealership at the beginning of her project to benchmark different types of vehicles. To better understand their target customers, students took turns positioning a baby seat, stroller and life-size doll in each car, testing the fit, function and ease of use in different models.

“It was so realistic, people almost reported us for leaving the doll next to the street in the hot sun,” she recalls with a laugh.

The method is similar to one Dr. Brooks does with her students in automotive engineering every fall. Prior to COVID, students donned pregnancy suits to simulate the dimensional changes of carrying a baby, then tries getting in and out (ingress and egress) of different types of cars. The difference between maneuvering into a slim BMW i8 and a van with a sliding door is staggering, she says.

Built for industry

A crucial component of Deep Orange is how students work closely with industry leaders. With their knowledge and experience in the automotive field, companies offer students a window into industry that few other graduate students can access.

As students attempt one of the most challenging programs of its kind, mentors guide them to avoid common pitfalls, develop interpersonal skills and ingrain best practices to help them after graduation.

Suzanne Dickerson helped the founder of the program, Dr. Paul Venhovens, to first get feedback from OEM partners on how the Deep Orange model would be received, then work with partners to secure components to be integrated into the prototypes. The response was overwhelming, she says.

Since its inception, Deep Orange students have worked with dozens of sponsors ranging from major OEMs and Tier 1, 2 and 3 suppliers to non-traditional companies leading the way in the sustainable mobility space. For Julie Jacobs, global design manager at Sage Automotive Interiors in Greenville, working with Deep Orange students has become a consistent and rewarding component of life at CU-ICAR.

“Deep Orange inspired me just as much as we inspired them,” says Julie. “Not just the fact that we’re helping them select materials, but thinking through what that design selection process is.”

As a leading supplier of high performance fabrics, Sage focuses heavily on trend research and development for the next generation of automotive interiors. Sometimes students were part of that trend research, offering their perspectives and insights as part of their collaboration with the company.

“The Deep Orange project is a huge challenge, and it changes every year with different sponsors and expectations,” she says. “It’s an interesting dynamic and we’re glad to be able to support it.”

In the color, material and finish space (CFM), Julie notes her male colleagues tend to be drawn to exterior vehicle design, while most of textile designers are female. Being a successful leader in the space is less about innate ability or interest, she says, and more about not about embracing design thinking, collaborative working methods and realizing that

“Playing and enjoying it as a journey, those are the characteristics I look for in a leader,” she says. “They don’t see gender, color, race, they just see opportunity and hope. They realize the best design is really the goal, and a functional one.”

“If more women applied that kind of thinking and approach, I think those would be the gods of the industry.”

“Women engineers think about different problems that may apply to women as consumers. The balance is very important – we need many different voices in engineering team to make the best result.”

YANG YANG, DEEP ORANGE 7 | FORD MOTOR CO.

According to Deloitte, women influence more than 80 percent of all new car purchases, yet they make up only a little over one-quarter of the automotive industry’s workforce – but that might change soon. With a tight labor market and intense engineering talent war, some auto companies recognize women as a competitive advantage in the years ahead.

“Successful companies know that women are exceptional leaders so they are focused on bringing more of them into their organizations and promoting them,” says Suzanne Dickerson, now South Carolina Director of SC Logistics who helped develop the Deep Orange program in 2009. “In my view, the automotive industry is the most exciting industry in existence. And the continued success of this industry in the future will depend on the women in it.”

Changing culture one engineer at a time

Bhavya Mishra has always been fascinated by how things work. From her first foray into automotive engineering with her undergraduate Formula SAE team to her work today at Tesla, she prioritizes learning and understanding to make her a better engineer. Despite her experience, she says, it’s still difficult to shake off the disparities between her and her male teammates.

“Even if it wasn’t overt discrimination, the little things add up,” says Bhavya, who won both a corporate fellowship as well as an outstanding student award while at Clemson. “The first thing I heard after I won was that someone else must have really fought for me, that I only won it because I was a girl. People already thought that maybe I didn’t deserve it, and I got caught up in thinking that as well.”

“When I looked at it from a logical perspective, I deserved it. It took me a long time to accept that.”

BHAVYA MISHRA, DEEP ORANGE 9 | TESLA

The research backs her up. According to the American Sociological Association, women don’t develop ‘expertise confidence’ as quickly as men, making them feel out of place and pushing them out of STEM fields. Studies are also lacking in evidence women leave engineering because of families or deficient math abilities. Instead, the difference seems to stem from subtle differences in the way men and women are treated, often expressed as unconscious micro-biases and micro-aggressions.

Programs such as Deep Orange can go a long way to build that expertise confidence by exposing them to the full range of vehicle design. The challenge — and success — offers tangible evidence of their expertise and capabilities.

“I have a lot to thank Deep Orange for,” agrees Rivkah. “I was able to run meetings and lead a team. I’m not afraid to speak up with questions or say, I disagree with you.’ Each year when I look back at the choices I’ve made and things I’ve accomplished, I don’t think I’d ever been able to do that if I hadn’t led Deep Orange.”

Another culture shift is the stigma around failure, says Bhavya. Rather than feeling ashamed or defeated about missing a target or a failed solution, bouncing back with resilience has opened more doors than she ever could have imagined.

That lesson hit hard while working on her university’s Formula SAE team, a student competition where students conceive, design, fabricate, develop and compete with small, formula-style vehicles.

“We failed miserably. The team fell apart, the car fell apart, our self-esteem fell apart. It was a horrible ending but such an amazing experience that I knew I could do this for the rest of my life,” she remembers. “Back then, it was awful, but even in retrospect, it was magnificent.”

Today, Bhavya can be found in the San Francisco Bay area designing and integrity-testing structural components like doors and hoods for the Tesla Cybertruck, slated for production in late 2021 and available to consumers as early as 2022.

Role models matter

Part of the challenge in recruiting and keeping more women in the auto industry could be the lack of female role models and mentors. Leaders such as GM’s Marry Barra are certainly part of a pivotal shift for women in the industry, but the gap still remains.

“If we keep letting the engineering world be overwhelmingly men, I think younger students when they’re choosing their future careers will automatically delete it as an option – they’ll think it’s not something for them,” says Yang, who thanks her supportive parents for enabling her to embrace her love of science and math at a young age. “If we have more women in engineering, it will give more women and future generations the idea that they can be a part of this field too.”

Rivkah’s love of cars started with her father, whom she calls “a huge car guy.” From there, she started to appreciate the complexity of those powerful machines and realized she wanted to be a part of it. In response to the guidance and support she’s felt from other successful women across her career, Rivkah feels compelled to pay it forward for the next generation of leaders.

“I would love to share what I’ve learned, whether it’s saying I feel your pain or your happiness,” she says. “Sometimes the hurdle becomes a lot less intimidating when you know someone else has been in that situation before and gotten through it.”

Now in its 12th year, Deep Orange draws more women each year from around the world to learn, grow and succeed in automotive engineering. The ExxonMobil-sponsored Deep Orange 11 team boasts women in all levels of leadership. The most recent prototype – an autonomous Indy racecar sponsored by EY – relies heavily on women for pivotal roles in programming, structures and leadership.

“If you love cars, love getting people moving, love making things greener, definitely pursue a career in automotive education,” says Rivkah. “Whether you’re a male or a female, everyone should have the opportunity to do what you love as a career.”