Malcolm Williams doesn’t think he’s remarkable.

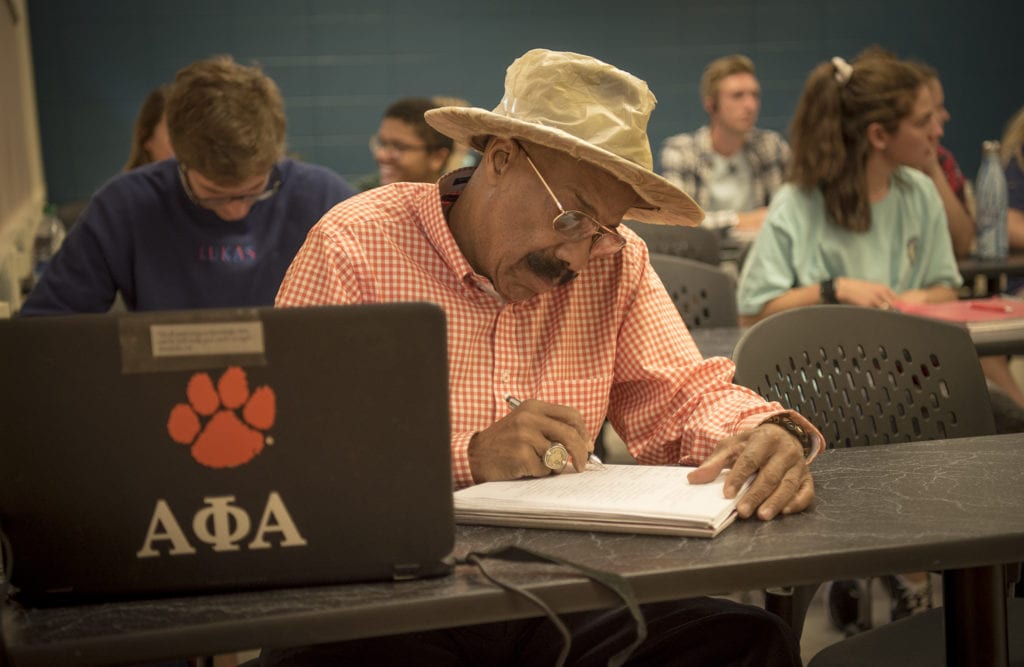

“I don’t know what story you can write about me except that I’m here,” quipped the dapper 78-year-old during an interview in his modest apartment just off the Clemson University campus. Dressed in his typically stylish manner, with dress slacks, a button-up shirt, and fine leather shoes, Williams certainly doesn’t look 78 and, as a college sophomore studying computer information systems, doesn’t act 78 either.

But there’s nothing extraordinary about that, he says. He isn’t back in school in his late 70’s because of some insatiable zest for life. He just needs a good job.

“Everything I’ve done in life I’ve done late. I’m the only clown in my whole family that didn’t get a degree,” he explained. “When they started dying on me I said I’d better get back to school.”

Both of his parents and his only sibling, a younger sister, have passed away, and since he’s fairly new to the Upstate he doesn’t have any close friends in the area.

“Basically, I don’t have anybody, let’s face it,” he says matter-of-factly. “It’s all up to me now.”

Williams has a tendency to downplay his life and didn’t particularly relish telling his story, but as he talks it becomes clear that, despite what he may think, he is quite extraordinary.

Born in 1939 in Highland Park, Michigan, his mother Esther was a substitute teacher, and his father David was a graduate of Columbia University who spent 50 years working at Ford Motor Company.

Because of his father’s position, Williams enjoyed a privileged upbringing, and could rely on support from his parents throughout his life. Nevertheless, he joined the Army in 1956 straight out of high school and served in both Korea and Vietnam as a surgical technician and was assigned to the 101st Airborne Division, the “Screaming Eagles.”

He experienced the South for the first time when he was sent to Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas for medical training. It was his first time away from Michigan.

“When I got to Fort Sam, I had never seen signs that said ‘Black Only’ or ‘White Only’,” he said. “It was a real eye-opener. I said oh mercy this is going to be pure hell and it was.”

Williams was sent to a Nike missile base in Illinois, and then to Fort Campbell, Tennessee. They gave him the nickname ‘Doc.’ One night he went to a local bar with two dozen soldiers from his company and experienced a scene right out of a movie.

“The guy behind the bar looked right at me and said ‘I don’t serve …’,” and he used a racial slur, recalled Williams. “The guys in my group said, you ain’t going to serve who? They said, well guess what – if you don’t serve Doc you won’t serve any of us. We all walked out together and never went back.”

That was his first taste of a brotherhood that would follow him all the way to Clemson.

Williams’ Army career took him all over the country, and the world. He was stationed with the 249th Surgical Detachment at a mobile army surgical hospital (MASH) in Korea, and then in the U.S. Army 3rd Field Hospital in Saigon, Vietnam. All told he spent six years in the Army caring for soldiers.

He downplays that too, balking at being called a hero, or even a veteran.

“I never saw war,” he said. “I got to Korea after the war, and then I got to Vietnam before the war, so I’m a peacetime veteran.”

His fellow veterans disagree with that assessment.

“The military needs all sorts of people doing all sorts of jobs to make it work,” said Sam Wigley, a Marine veteran, Clemson graduate, and outreach director for Upstate Warrior Solution, a nonprofit dedicated to helping veterans in the Upstate area of South Carolina. “I’m sure if Malcolm asked those wounded fellows he was working on if they thought he was an important part of the military and a veteran they would not hesitate to agree.”

Williams got out of the Army in 1962 as a specialist second class and spent the next few years trying to figure out what to do with his life. He describes a definitively 1960’s Detroit existence during those years. He tells of dating songwriter Janie Bradford, who wrote “Money, (That’s What I Want)” and several other hits, while he was still in the Army. He says that while he was with her he became something of a fixture at Motown’s Hitsville U.S.A. studio.

“Janie and I dated for four years. She had three secretaries at one time at the Motown office and I had to go through all three just to meet her for lunch,” he laughed. They also put him to work. At one point he was enlisted to chauffeur The Supremes to appearances.

“My dad had a convertible Thunderbird and [Motown founder] Berry Gordy would ask me to ride the Supremes around in it. I didn’t like him, but at the time the Supremes were struggling, so I said I can’t do this all the time, because it’s my father’s car, but I’ll take you around,” he chuckled.

He landed work as a professional bartender in the Detroit club scene, where he rubbed elbows with people like Jackie Wilson and Dinah Washington. After that he moved to California for a time (“People are kooky there – I think they get too much sun.”) and then returned to Michigan to attend college at Ferris State College in Big Rapids, where he became a charter brother of the school’s Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity chapter in 1966. He left before graduating when state funding to the school was cut, leaving him without the means to continue.

He spent the next portion of his life as an auditor for technology companies, which kept him moving around the country until an old Army friend convinced him to move to Greenville in 2001, where he worked for Columbus Serum Company until the company was sold in 2008.

Suddenly and unexpectedly, he was 68 and unemployed. Retirement was not an option – that’s what old people do. It was time to figure out the next chapter. In the meantime, he found a place in the Broomfield Senior Living center.

“I didn’t like the ‘senior’ part,” he laughed. “Everybody there was just vegetating.”

Williams knew that he couldn’t become stagnant. He recalls Henry Ford II at his father’s retirement ceremony asking, “Well Dave, what are you going to do now?”

“My dad said ‘I’ll keep at it,’” said Williams. “But he didn’t. He only lived two years after his retirement. It was tragic. He was 72 when he died and he should have had all kinds of years left.”

Already having outlived his father by several years, he enrolled at Greenville Technical College to avoid the same demise.

“I have a Ph.D. in dressing. I can tie a bow tie. But I’m tired of just looking like I’m educated, so I enrolled,” he said, “Because I want to be educated, not vegetated.”

After several semesters at Greenville Technical College, Williams decided to seek a four-year college degree. He set his sites just down the road on the home of the Tigers. He’d heard nothing but good things about Clemson since moving to South Carolina, so he figured he might as well go for the best.

He applied and, being an honor student at GTC, was immediately accepted. Now his only problem was getting to class. Clemson was an hour-long bus ride away, and that sufficed for a while, but it was exhausting. He needed to move closer, but he hadn’t worked since 2008, so he had no resources to make that happen.

That’s when his brothers-in-arms stepped in. When Wigley and the other administrators of Upstate Warrior Solution found out Williams was in need, they contacted the Clemson Student Veteran Association to help. On a cool and overcast Saturday this past January, a squad of Clemson student veterans, strangers until that moment, showed up at Williams’ apartment in Greenville. They loaded his belongings into their cars and moved him to an apartment they had found for him in Clemson. He was one day away from the end of his lease.

It was a reminder from his fellow veterans that, even though he might feel alone sometimes, he is not and never will be.

“This is anecdotal evidence of what every veteran knows: that the bond between service members transcends race, gender, generational gaps, political affiliations, military branches and occupations, and even wars,” said Brennan Beck, Clemson’s assistant director for Military and Veteran Engagement, who was one of the vets that helped Williams move that day. “Despite all of our differences, we’re connected by what unites us: our sworn service to defending and serving our country in the U.S. military. That’s the strongest bond.”

Williams says those student veteran Tigers probably kept him from going homeless that day. He’d had a few reservations about coming back to the American South, where he first experienced blatant racism, but those fears abated as his fellow vets and the greater Clemson Family welcomed him with open arms.

“I did have a few unpleasant thoughts about coming back to the South,” he said. “However, while I have struggled to adapt to university life, Clemson’s administration and its faculty continue to encourage me and treat me with dignity and respect.”

Now, Williams gets up every day and goes to class like very other student and hopes to become a consultant after graduating two years from now, at the age of 80.

“I used to say, ‘Oh well I’ve got time,’” he reflected. “Well, you don’t have time. Believe me. You get to be 20, all of a sudden you’re 30, then all of a sudden you’re 40. Hey, time flies – next year I’ll be 79 and I’m still trying to get an education.”

Williams has taken up studying German in his spare time and likes to recite his favorite quote: Wir werden zu früh alt, schlau zu spä.

“It means ‘We get old too soon, smart too late,’” he said, nodding gently. “Don’t I know it.”

Whether he knows it or not, he’s having an impact on the people around him just by being here.

“He inspires me,” said Ken Robinson, associate professor of sociology, anthropology and criminal justice and a charter member of Clemson’s chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha. “To hear his story is very encouraging. I was introduced to Malcolm by a graduate student who knew that he was an Alpha and recommended that I meet him. Well, I reached out to Malcolm and I’m very pleased that he’s here. I think it’s really good for his fellow students to interact with him, and to learn from his rich experience.”

Williams remains nothing if not pragmatic about what lies ahead for him.

“I’m going to stay with it until I graduate, if I live,” he said, pensively. “When I dress up I want that big Clemson ring on my hand. Dylan Thomas said ‘Don’t go gentle into that good night. Rage, rage against the dying of the light.’ That sticks in my mind all the time. If I go out of here I’m going out kicking and screaming, and that’s a fact.”