People passing by Memorial Park on the Clemson University campus Friday morning June 3, 2022, might have seen what looked like a typical group of visitors getting a tour of the carefully manicured grounds that sit directly across from Memorial Stadium. A cluster of grandfatherly men, some using walkers, most flanked by their wives or other family members, followed attentively as their tour guide walked them through the thoughtfully layered symbolism of the park, which was designed to honor Clemson Alumni who died while serving their country in the military.

This was far from a typical tour group, however, because the men at the center of it all survived being prisoners of war in Vietnam. The visit was part of the Vietnam POWs Return to Freedom 49th Anniversary Reunion, organized by the Vietnam POW Reunion Foundation and NAMPOW, the national organization of former Vietnam POWs.

The POWs were given the tour of Memorial Park by members of Clemson Corps, who treated the occasion with great reverence. The tour ended in silence at the Scroll of Honor, the raised burial mound that is the centerpiece of the park. It displays the names, etched in individual stones that ring it’s gentle slope, of all 497 Clemson alumni who gave the ultimate sacrifice. The POWs and their escorts took their time at the Scroll, walking around it and quietly reading the names in the stones as a light breeze rustled the leaves of the trees that surround the memorial.

The tour of Memorial Park was followed by a tour of the Allen N. Reeves Football Complex given by Tracy Swinney, director of football security and community liaison for the football program. Swinney elicited hearty laughter from the group multiple times as he showed them around the state-of-the-art complex, pointing out luxuries like the miniature golf course and nap room the men could never have imagined during their years in uniform, and teasing a couple of them who had University of Alabama caps on. Head coach Dabo Swinney made a point to break away from his coaching duties to address the group as it was passing through the dining hall.

“None of us would have what we have or enjoy the freedoms we have without heroes like you,” Swinney told the group. “We are so honored to have you here today.”

The POWs’ visit ended with a catered lunch in the West End Zone of Memorial Stadium.

Vietnam POWs represent a generation of warfighters that has become legendary among veterans and current members of the military. The POW group at Clemson on Friday included some of the most experienced and highly decorated veterans living today. In the present-day military, it is very rare to serve alongside someone who has received an award for valor in combat like the Silver Star or the Bronze Star, but Vietnam POWs wear more medals on their uniforms than buttons. Just a few who graced the Clemson campus Friday were:

Elmo “Mo” Baker, who spent 2,030 days in captivity and earned four Silver Stars, four Distinguished Flying Crosses and three Bronze Stars.

Tom McNish, who spent 2,373 days in captivity and earned three Silver Stars, a Distinguished Flying Cross and three Bronze Stars. Seen here giving Dabo Swinney a challenge coin.

Al Agnew, who spent 91 days in captivity and was the last American POW released by the North Vietnamese.

Bob Shumaker, who spent an unimaginable eight years and one day in captivity and coined the term “Hanoi Hilton,” referring to the notorious prison camp in North Vietnam.

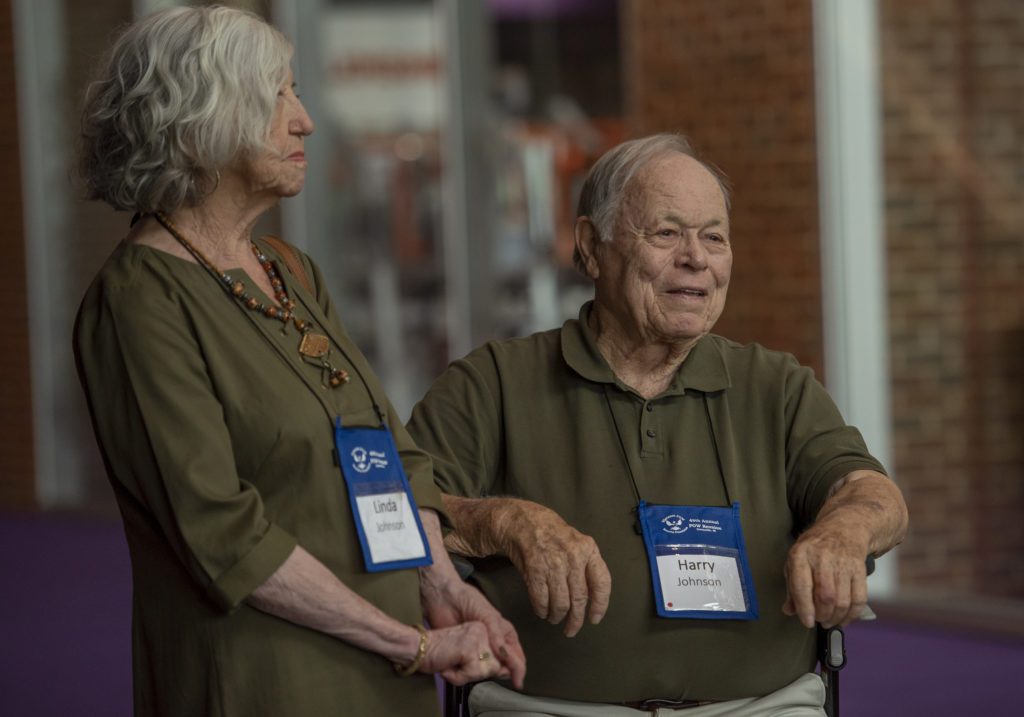

Harry Johnson, who spent 2,135 days in captivity, and is the recipient of the Air Force Cross, two Silver Stars, six Distinguished Flying Crosses and two Bronze Stars. Seen here with his wife, Linda in the Allen N. Reeves Football Complex.

Richard Thomas Simpson, whose father, Arthur Thomas Simpson, was a 1940 graduate of Clemson who served with the 104th Infantry Regiment in World War II, was killed in action in France on November 18, 1944, and has a stone in the Scroll of Honor.

1959 Clemson alumnus Bill Austin, who spent 1,986 days in captivity, is the recipient of two Silver Stars, two Distinguished Flying Crosses and two Bronze Stars.

Being held as a prisoner of war and surviving captivity has always been an exceedingly rare distinction among service members, rarer even than medals for valor. With the technological and strategic advancements of modern-day warfare, as well as better training of the troops, it has been nearly nonexistent since Vietnam, so having so many POWs in one place was an unforgettable experience for those who helped organize and lead the Clemson tours.

Most of the American POWs captured in South Vietnam, North Vietnam and Laos were held in Hanoi in a French-built prison called Hoa Lo. The American captives humorously called their dark and dangerous cells the “Hanoi Hilton.” Six smaller prisons within 100 miles of the city held most of the Army and Marine Corps POWs captured in South Vietnam. There were over 20 escape attempts, but no POW ever successfully escaped from Hanoi. Most of the POWs shot down and captured in North Vietnam (468) were aircrew personnel of the U.S. Air Force (319), Navy (140) and Marine Corps (9).

In total, 662 POWs survived the Vietnam Conflict. According to the Vietnam POW Reunion Foundation, only 407 of those men are alive today, seven of whom live in South Carolina.