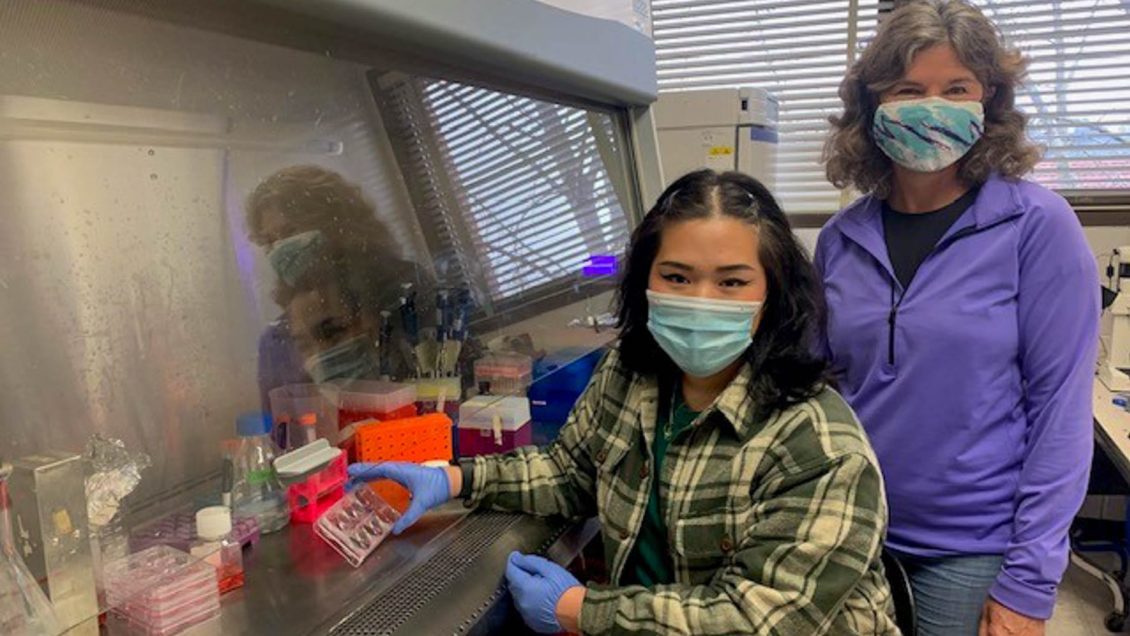

Clemson University scientist Lisa Bain has received a National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences grant to continue researching the effects of arsenic exposure.

The three-year, $441,662 R15 grant will allow Bain and her team of graduate and undergraduate researchers to examine how arsenic affects adult intestinal stem cells.

Arsenic is a contaminant in both drinking water and food. Chronic exposure to unsafe levels can cause a myriad of health issues, including developmental impairments, adverse birth outcomes and an increased risk of cancer.

Bain’s past research centered on investigating how chronic low-level arsenic exposure impacts cell differentiation during embryogenesis.

“For many years, we’ve been investigating what happens if you’re exposed to toxicants early on during development. Can you form muscles properly? Are the neurons forming in your brain talking to each other appropriately? Do you have enough stem cells so if you get injured, later on, you’ll be able to repair yourself?” said Bain, who specializes in toxicology in the College of Science’s Department of Biological Sciences.

But cell differentiation is not limited to embryos, fetuses or even young children.

Adults slough off their intestinal lining every five to seven days and rely on stem cells to divide and differentiate into cells that digest food, absorb nutrients and secrete mucus. This new project will investigate arsenic’s effect on adult intestinal stem cells.

Different way of thinking

“Many times, we think of the intestine as a tube for absorption of pharmaceuticals or toxicants, and then those substances go on to affect other parts of the body,” Bain said. “This is a different way of thinking. We’re thinking about the effects of chemicals on the intestine itself.”

Suppose arsenic causes the intestine to produce fewer cells that absorb nutrients. In that case, it could affect the body’s ability to nourish itself properly and limit a person’s ability to thrive and grow.

“If we understand what arsenic is specifically doing to these cells, it opens the possibility of nutritional supplementation or pharmaceutical intervention,” she said. “We’re hoping these studies will help us better understand these processes of absorption.”

Pilot study

Bain’s lab did a small pilot study that exposed mice to arsenic for approximately one month. Researchers saw changes in the ability of stem cells to divide properly. In that study, arsenic affected the mice’s ability to produce Paneth cells, which Bain called a nurse for stem cells.

“We’re focusing on the mechanisms by which cells respond to arsenic found in food and drinking water,” she said.

Arsenic occurs naturally in bedrock and sediments and can leach into groundwater and infiltrate water wells. The World Health Organization estimates at least 140 million worldwide, including up to 13 million Americans, have been drinking water containing arsenic at levels above the safety threshold of 10 parts per billion. The problem of arsenic-contaminating drinking water is especially acute in Bangladesh, India and Taiwan. In the U.S., the major trouble spots for arsenic are the desert Southwest, Maine, New Hampshire, Minnesota and North Dakota. A recent study by the U.S. Geological Survey estimated that during drought conditions, 4.1 million people in the continental U.S. who rely on private wells for their drinking water could be exposed to unsafe levels of arsenic. About 2.7 million Americans are exposed to harmful arsenic levels during non-drought conditions.

Besides water, arsenic is found in food, especially in rice. Cotton farmers used to use arsenic as a pesticide long ago and the toxin remains in the soil. Many of the former cotton fields now produce rice. Growing crops absorb arsenic when paddies are flooded.

The College of Science pursues excellence in scientific discovery, learning and engagement that is both locally relevant and globally impactful. The life, physical and mathematical sciences converge to tackle some of tomorrow’s scientific challenges, and our faculty are preparing the next generation of leading scientists. The College of Science offers high-impact transformational experiences such as research, internships and study abroad to help prepare our graduates for top industries, graduate programs and health professions. clemson.edu/science

Get in touch and we will connect you with the author or another expert.

Or email us at news@clemson.edu