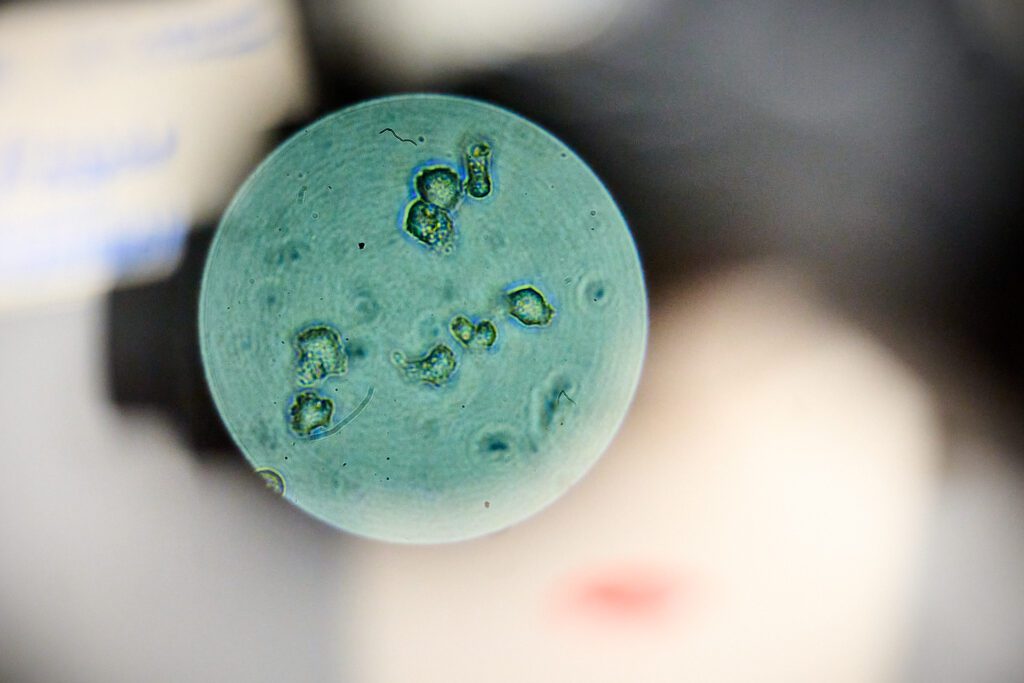

A Clemson University biologist is studying whether an existing drug could treat Acanthamoeba keratitis, an eye infection that primarily affects contact lens wearers and is caused by a parasite that lives everywhere from soil to tap water.

The amoeba, Acanthamoeba castellanii, leads to one to two new cases per 1 million contact wearers annually in the United States. Clemson had two cases of the rare infection about 10 years ago.

The infection is currently treated with painful and potentially damaging drops, but Lesly Temesvari, Alumni Distinguished Professor and associate chair of the Clemson Department of Biological Sciences, is looking at an option that may improve outcomes.

Majority of cases occur in contact lens wearers

About 85% of cases of Acanthamoeba Keratitis occur in contact lens wearers, especially those who rinse contacts in tap water or swim or shower while wearing their contact lenses.

Occasionally, Acanthamoeba keratitis results from corneal trauma in non-contact lens users.

Patients often have severe eye pain, redness and extreme light sensitivity. Health care providers often misdiagnose cases as viral or bacterial keratitis and prescribe antiviral or antibacterial eye drops, but these treatments do not help. A quarter of Acanthamoeba keratitis cases end up requiring corneal transplants.

Temesvari recently received a National Institutes of Health grant to investigate repurposing an already existing drug to treat Acanthamoeba keratitis.

Current treatment is chemical found in pool sanitizer

The current treatment is eye drops that contain a chemical called biguanide, commonly found in Baquacil, a pool sanitizer. Patients must put drops in their eyes every hour, around the clock at the beginning of treatment, before tapering off. Treatment can last from six months to a year. The drops can be painful to apply and can cause damage to the eye.

Temesvari stumbled upon a new potential treatment when she was teaching a cellular biology class. A student asked her about a protein called thymosin beta-4. Temesvari was unsure how to answer the question so she told him she would do some research.

“Between the next two classes, I started reading about thymosin beta-4, and I almost fell out of my seat because it has this ophthalmic use. I’m like, ‘Oh my gosh, we can use this to treat Acanthamoeba infections,’” Temesvari said.

All human cells, except red blood cells, contain thymosin beta-4. This protein usually regulates actin, which helps with cell movement and structure, but scientists recently found a moonlighting function of thymosin beta-4.

Through cell signaling, thymosin beta-4 also aids in wound healing and scar formation. The protein is currently in clinical trials to treat dry eye syndrome and neurotrophic keratitis, a degenerative corneal disease. These trials are showing positive results, like increased healing in a shorter time, and have thus far had no adverse side effects.

Temesvari wanted to test how thymosin beta-4 could be used to treat acanthamoeba keratitis. She and her team grew corneal and retinal cells in tissue culture plates until the cells created a monolayer over the entire plate. They then applied the amoeba parasite and incubated it with the cells. The researchers stained, imaged and examined the percentage of the monolayer left to see the effect of the amoeba. They then compared cell death with and without thymosin beta-4.

Temesvari found that with thymosin beta-4, 90% of the monolayer remains after parasite infection compared to 65% without thymosin beta-4. Thymosin beta-4 provided the same level of protection whether added at the same time as or before the parasite, so Temesvari hypothesizes that the protein affects the host cells rather than the parasite.

Two life cycle stages

The amoeba has two life cycle stages: an active amoeba and a dormant cyst. When the amoeba form is stressed by something like starvation, it changes into a cyst, which is more environmentally stable with longer viability. When patients treat an Acanthamoeba keratitis infection with eye drops, the amoeba is stressed and becomes a cyst. These cysts resist treatment and can remain in the eye for up to two to three years. When patients get corneal transplants, a cyst could reinfect their eyes. Temesvari has shown that thymosin beta-4 can inhibit the transformation from amoeba to cyst.

“So, you can imagine we could do a combination therapy with an antimicrobial agent to kill the parasite and thymosin beta-4 to protect the cornea and prevent stage conversion in the parasite simultaneously,” she said.

This summer, Temesvari plans to take the experiment a step further by purchasing special cells called an EpiCorneal, which is a 3-D tissue model that layers different cells to create an artificial cornea. She will infect these cells with the parasite to see how thymosin beta-4 protects against infection. Temesvari’s grant collaborator at Purdue University, Christopher Rice, will also test the parasite’s effect with thymosin beta-4 on infected cow corneas grown in culture.

The additional 3-D testing will account for the parasite’s ability to burrow into the cornea and allow for simultaneous testing of the parasite’s impact on different cell types in the eyes.