Before Rod Andrew became a professor in Clemson’s Department of History & Geography, he was a Marine. Retired Colonel Andrew is a veteran of Operation Desert Storm, serving four years as an active duty member of the Marine Corps and 25 years in the Reserves.

Andrew’s dual identities as an historian and Marine bring perspective to his new book, The Marines’ Fight for Survival: War, Politics, and Institutional Crisis, 1945-1952, which chronicles the Corps’ battle to retain its existence as a distinct branch of the United States Armed Forces following World War II.

According to Andrew, it was a struggle that has shaped the Marine Corps’ identity to the present and offers instructive lessons for its future. He sat down with Clemson News to explain how the book came to be, what his research uncovered, what readers should glean from the book and more.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Clemson News: What led you to write this book?

Andrew: I had already been becoming more and more involved in American military history over the latter decade of my career. Especially in my Marine Corps Reserve job, I was a field historian for the Marine Corps History Division, so I was involved in writing projects and supervising other historians.

But about ten years ago, my oldest daughter bought me a book for Christmas, Underdogs: The Making of the Modern Marine Corps by Aaron B. O’Connell, who was another fellow Marine Corps Reserve officer and professional historian. And there was one chapter in the book that really dealt with this crisis to the Marine Corps’ existence in that decade — the mid-1940s to the 50s. It was a story that most Americans have no memory of and no knowledge of.

Like most Marines, I was just vaguely familiar with it, but I knew how important it was. I thought, “This is a story that needs to be told in full.” It’s never been told fully, but it has a huge impact on the Marine Corps today.

CN: What was threatening the Marines’ survival as an institution after WWII?

Andrew: It was the hostility and the jealousy, but also the genuine and understandable concerns of the key leaders of the War Department and President Harry S. Truman himself.

So we’re talking about Dwight D. Eisenhower, Chief of Staff of the Army after World War II; George C. Marshall, former Chief of Staff of the Army, who was continuing to play a huge role in government; Omar Bradley, who would become the Chief of Staff of the Army and several high-ranking Air Force generals.

Truman was a former army officer himself, and there was a great deal of bitterness amongst some of these senior officers towards the Marine Corps. You have to understand, when these guys were young Army officers, the Marine Corps was basically a naval constabulary. It was not a large combined-arms force capable of serious ground warfare. By the end of WWII, the Marine Corps had its own air wing, its own artillery, its own tanks and combat engineers. It had grown from two brigades to six full divisions. They saw it emerging as a, quote, “Second Land Army,” And they saw that as illogical and wasteful and a threat to the Army, particularly with all the glowing media attention and the popularity that the Marine Corps enjoyed.

I think what surprised me the most was the extreme bitterness of leaders like Eisenhower, Bradley and Marshall against the Marine Corps.

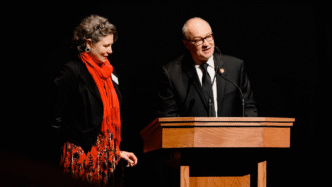

Professor Rod Andrew Jr.

CN: What were the emotional dynamics between the branches during that time period?

It started in World War I with the Battle of Belleau Wood, where a relatively small Marine unit, just a brigade, won an impressive victory. In France in World War I, the Army had lots of divisions, but this was one battle where the Marines did really, really well. No one denied how great a job they did, but they got media attention out of proportion to their numerical presence.

And then in WWII, operations like Guadalcanal, Tarawa and Iwo Jima got tons of glowing press coverage, as opposed to larger Army operations . . . It drove General Marshall crazy how much publicity the Marines were getting, and the Marines were just better at producing publicity.

CN: Did this period of having to fight to maintain its own identity inform the Marines’ self-identity and distinctiveness to this day?

Andrew: One point I make in my book is that this has been an ongoing struggle for the Marine Corps to define its identity, because it’s not intuitive that nations need a Marine Corps.

This was at least the ninth attempt to either abolish the Marine Corps, absorb it, or to radically alter its role so much that it was not relevant. So this ongoing struggle for survival has defined the Marine Corps’ identity, and just about every single time, it was Congress that stepped in to save the Marine Corps.

The attacks came from the other services or from the executive branch, so the Marines’ survival was due to the Marine Corps’ popularity with the public. The Marines were always praised for their valor, their discipline, their effectiveness in combat, even by the other services, and that translated into popularity with the public and support in Congress.

I think that’s why when I read the book by O’Connell, it made so much sense to me, because that’s something that I absorbed intuitively throughout my career as a Marine. You know, the Army can lose a battle, the Navy can lose a battle, but if the Marine Corps loses a battle, then its reputation for invincibility is destroyed, and its love affair with the American public is destroyed, and it’s in great danger. That may not be objectively true, but I think it’s something that Marines feel very deeply.

CN: What was the turning point in this struggle?

Andrew: There were several key events. One was a speech by Commandant Alexander Archer Vandegrift given to the Senate Naval Affairs Committee in 1946, and it’s called the “No Bended Knee Speech,” and he said “the bended knee is not a tradition of our Corps.” It got huge publicity and electrified the hearing chamber.

There was another key speech by the next Commandant Clifton B. Cates in 1949. I argue in my book that all along, there were a lot of backdoor deals, leaked documents and lobbying that kept the Marine Corps on life support until the Korean War. But it was the Korean War and the Marines’ performance that made it politically impossible to keep going after the Marine Corps.

CN: What surprised you most in your research?

Andrew: I think what surprised me the most was the extreme bitterness of leaders like Eisenhower, Bradley and Marshall against the Marine Corps. I make a point in my book to point out the sincere concerns and the patriotic services of those men. On the other hand, Eisenhower was at best misleading and at worst dishonest about his designs against the Marine Corps.

CN: What do you hope people take away from reading your book?

For non-Marines, I would like there to be a better understanding of how unique the U.S. Marine Corps is. I think Americans take it for granted that, for example, we have the only Marine Corps with not only an air wing, but a very robust and effective one. It’s just about the only Marine Corps in the world with its own artillery and — until recently — its own tanks.

And the Marine Corps, as we speak, is in the middle of a real doctrinal and strategic crossroads. I would like to see mid- and senior level officers and future senior-level officers see what a fight it was for the Marine Corps to have the combat arms capability and strategic relevance that it has. I don’t want them to take that for granted.