Her research aims to revolutionize treatment for atherosclerosis, a leading cause of death worldwide.

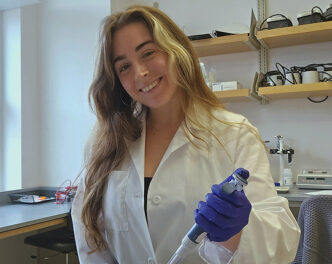

When Ally Brawner transferred to Clemson University as an undergraduate in plant and environmental sciences, she sought more than a degree—she wanted opportunities to learn, grow and make an impact.

As a graduate student in the College of Agriculture, Forestry and Life Sciences, Brawner has done just that. Her research could one day transform how doctors treat atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), the world’s leading cause of death. ASCVD is caused by plaque buildup in the arterial walls of the heart. It refers to conditions that include coronary heart disease, such as myocardial infarction, angina and coronary artery stenosis.

“I came to Clemson because it offered scholarships and hands-on experiences,” said Brawner, who will graduate with a master’s degree on Dec. 18.

From farm to lab: a journey of discovery

Raised in San Angelo, Texas, as a self-described “military brat,” Brawner grew up moving frequently. But Clemson quickly became home. After completing her bachelor’s degree, she pursued a master’s degree in the food, nutrition and packaging sciences program.

Her master’s work focuses on developing a therapy for atherosclerosis using nanotechnology. She will continue her studies at Clemson as a doctoral student under the guidance of associate professor Alexis Stamatikos, advancing her research to the next level.

The problem: a costly and deadly disease

Atherosclerosis occurs when cholesterol builds up in the arterial walls, forming plaques that restrict blood flow. It’s the primary driver of heart attacks and strokes. Information from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows Americans spend about $400 billion annually on cardiovascular disease, much of it on statins, or medications that lower LDL (bad) cholesterol. Yet, many patients still die from the disease.

“Statins work in the liver, but plaque develops in the vascular system,” Brawner explained. “Our approach targets the problem where it starts.”

Arteries carry blood away from the heart. Arterial walls consist of three layers to provide support and regulate blood flow and pressure.

The solution: nanotechnology meets nutrition

Brawner’s research uses polymersomes—tiny, engineered nanoparticles—to deliver therapeutic plasmid DNA directly to arterial cells affected by atherosclerosis. These tiny particles are coated with a special protein chain that sticks to a marker found on blood vessel cells when the cells are inflamed.

Inside the polymersome is a set of instructions (DNA) that tells the cell to turn off a tiny switch called miR-33a-5p. This switch typically prevents the cell from removing cholesterol. When turned off, the cell produces more of a helper protein (ABCA1) that pushes cholesterol out. That cholesterol then joins HDL (good cholesterol), which acts like a garbage truck carrying fat away from arteries to the liver, where it’s broken down.

“This therapy doesn’t just lower LDL like statins do,” Brawner said. “It helps clear cholesterol from the vascular system, addressing the root cause of plaque formation.”

Engineering challenges and breakthroughs

Building a delivery system for specific cells was tricky. Adding a VHPK “address label” to the nanoparticles sometimes caused them to stick together like” wet spaghetti,” which slowed them down.

Brawner worked on keeping them from clumping and ensured each one could carry more of the DNA instructions inside, like packing more letters into individual envelopes without them jamming together.

Her efforts paid off.

“We were surprised by the results,” she said. “Our optimized polymersomes significantly reduced miR-33a-5p expression and increased ABCA1 mRNA levels. It was very encouraging.”

VHPK is a key component in targeted nanomedicine research aimed at treating inflammatory vascular diseases.

Why it matters

This therapy could save lives and reduce health care costs. It could also serve as a preventive measure for patients at risk of developing atherosclerosis decades before symptoms appear, as well as complement existing treatments such as statins.

“This research addresses a major public health burden,” Brawner said. “It’s exciting to think about the impact.”

Next steps: from bench to bedside

Before the therapy can be tested in humans, Brawner and her team must conduct studies to determine how the treatment behaves in the body and what dosage is adequate. They’ll also assess serum stability and safety.

“Drug development is a long process,” she said. “But every step brings us closer to a potential solution.”

Passion for science and service

For Brawner, the project is more than an academic exercise; it’s a calling.

“This work combines nutrition, disease pathology and bioengineering,” she said. “It never gets boring. I love the challenge of applying benchtop science to real-world problems.”

Stamatikos considers Brawner “the ideal graduate student.” He hopes she stays in academia.

“Ally is very knowledgeable, passionate, hard-working, collegial, perseveres under pressure and is extremely enthusiastic about her project and several other projects ongoing in our laboratory,” Stamatikos said. “I believe every graduate student, regardless of what discipline, should emulate all these positive attributes, qualities and characteristics Ally displays.

“Her future is bright as a well-rounded scientist, whether she decides to stay in academia or ventures over to industry after completing her doctoral studies.”

In addition to Stamatikos, her other mentors, Jessica Larsen and Paul Dawson, have played a key role in her success.

“They push me to levels I didn’t know I could reach,” she said.

Looking ahead

Brawner wants to pursue a career in academic research, although she’s open to opportunities in industry. Whatever the future holds, her goal remains the same: to improve human health through science.

“I feel like I’m living a dream,” she said. “To be doing nutrition, drug development and bioengineering is incredible.”