Alyssa Baker, a second year Ph.D. student in the Clemson University Department of Biological Sciences, loves crustaceans.

“Visually, they’re really interesting animals. They have all sorts of body plans and colors. Some of them have remarkable behaviors as well. There’s a lot of important fisheries targeting many crustaceans. When I came to Clemson, I started scuba diving so it’s kind of combining what you like and what you do for work,” said Baker, who earned a master’s degree in biological sciences from Clemson in 2024. “And I think crustaceans are understudied, depending on what groups you’re focusing on.”

Biology of spiny lobsters

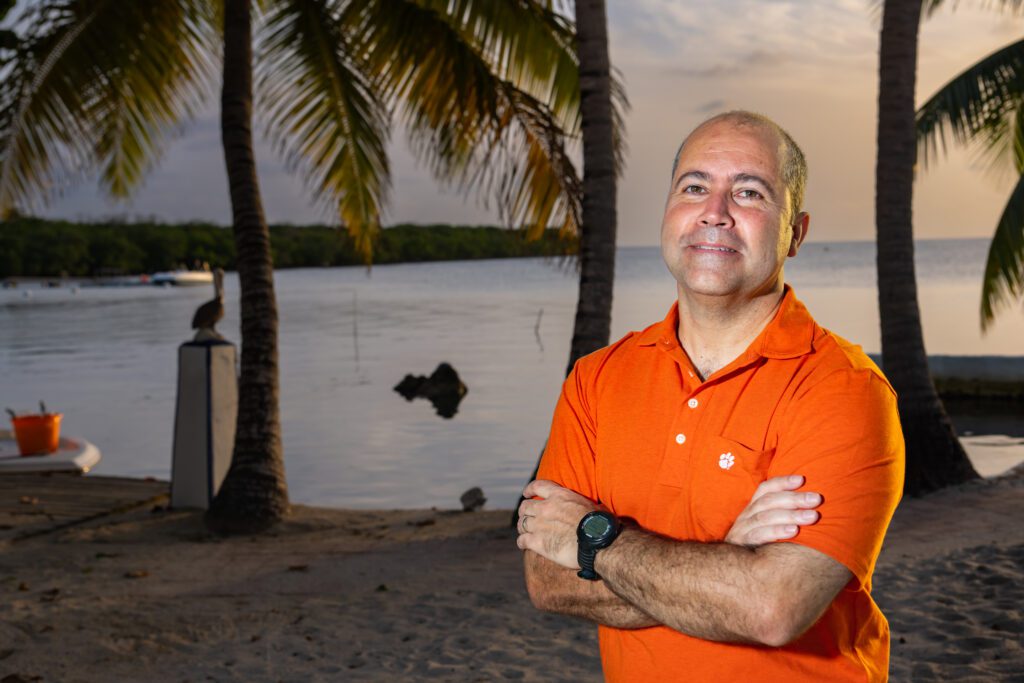

Baker, a member of Associate Professor Antonio Baeza’s lab, is currently studying many aspects of the biology of spiny lobsters.

She recently compiled the first nuclear and mitochondrial genomic portrait of the Juan Fernandez Islands rock lobster Jasus frontalis, also known as Robinson Crusoe’s spiny lobster.

Robinson Crusoe Island is the largest of the Juan Fernandez Islands and is 416 miles west of San Antonio, Chile, in the South Pacific Ocean. The island was home for four years and four months to marooned Scottish sailor Alexander Selkirk, who expressed concern over the seaworthiness of his ship, Cinque Ports, and was left there by Captain Thomas Stradling. It turns out his concern was valid as the ship sank shortly after.

Selkirk at least partially inspired novelist Daniel Defoe’s fictional Robinson Crusoe in his 1719 novel of the same name. The Chilean government changed the name of the island from Mas a Tierra to Robinson Crusoe Island in 1966 in part to attract tourists.

The Jasus frontalis rock lobster is endemic to the Juan Fernandez archipelago and Desventuradas Islands. It is a key part of the local ecosystem and economy. Decreasing catches with increases in fishing effort during the last decades suggests the lobster species is experiencing overfishing, Baeza said.

In this study, Baker generated for the first time genomic resources for the Robinson Crusoe lobster using new bioinformatics tools that can retrieve useful biological information even from limited genomic datasets.

Extracting genomic DNA

Using a muscle tissue sample from the Clemson Crustacean Collection, Baker extracted genomic DNA, which was sequenced using next generation sequencing technology. She then assembled the mitochondrial genome and analyzed the nuclear genome using bioinformatic tools.

“This sample is from a leg preserved in ethanol in 1996, so it’s actually been preserved longer than I’ve been alive,” Baker said.

The leg was donated to Clemson and Michael Childress, an associate professor in the Department of Biological Sciences, about 20 years ago by Ray George, one of the leading authorities on spiny lobsters at the time. Currently, the Clemson Crustacean Collection is small but is expected to growth with time and will support additional genomic research focused on imperiled marine species, both vertebrates and invertebrates, Baeza said.

Aid in identifying mislabeled lobster commodities

The biological insight generated in the study will contribute to the biomonitoring strategies targeting this species using environmental DNA and aid in surveying the public marketplace to identify mislabeling of spiny lobster commodities, Baker said.

“Mislabeling is a really pervasive problem for a lot of different marine organisms. Studies have been done with shrimp, but also with fish sold at sushi restaurants and even sharks,” Baeza said.

Baker’s research also includes understanding the historical biogeography of spiny lobsters, which describes how shifting ocean currents and continental drift or movements affected the diversification or speciation of spiny lobsters over millions of years.

There are 61 species of spiny lobsters. Five are in the genus Jasus. Baker is working on assembling mitogenomes for two more Jasus species — Jasus lalandii (Cape rock lobster, lives along South Africa) and Jasus paulensis (St Paul rock lobster, lives near Saint Paul Island in the Indian Ocean and Tristan da Cunha in the Atlantic Ocean) as well as several other related species of spiny and Spanish lobsters.

Detailed findings about the Robinson Crusoe spiny lobster can be found in the paper titled “A first nuclear and mitochondrial genomic portrait of Robinson Crusoe’s (Juan Fernandez Island) spiny lobster Jasus frontalis (Crustacea: Decapoda: Achelata).”