Jeff Marshall clearly remembers a student in his AP Physics class whose abilities were far beyond the material he was teaching. By the third day of the class, Marshall knew the student—who would later skip his first year at MIT—would quickly grow disinterested in the material. Marshall had to do something, so he started a “game.”

Every day, Marshall would give the student a question or high-level math problem on a half sheet of paper. Some would be silly, some would be unsolvable and others would just be thought provoking. It created a dialogue between them and kept the student challenged in the classroom.

“Years before ‘Mythbusters’ modeled it, I asked him if running or walking through the rain would bring him to his destination drier,” Marshall says. “Years later, during a teacher appreciation day, he called and told me that I was the only teacher that made it a priority to challenge him even though he knew the material being taught. That was a proud moment for me.”

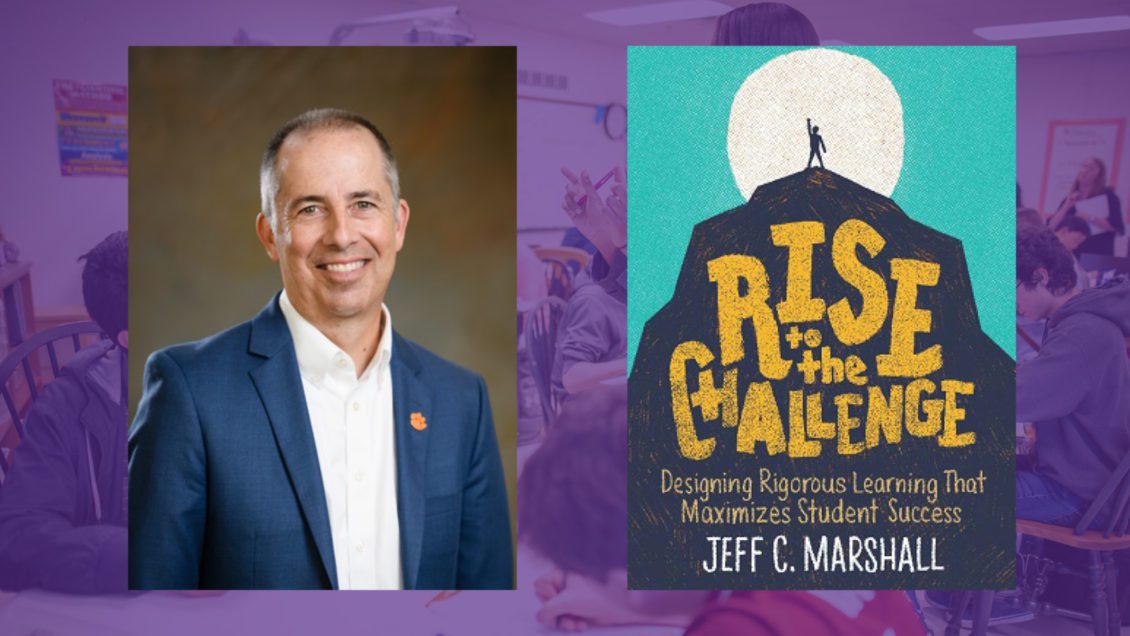

The ability to challenge all students in his class—from those bound for MIT or those that others would label “low performing”—made Marshall exceptionally qualified to write a book on the subject. His latest, “Rise to the Challenge: Designing Rigorous Learning that Maximizes Student Success,” tackles head on the challenge of introducing challenge in the classroom.

The book is Marshall’s sixth overall and his third for the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD). The book is also his second ASCD Member Book, meaning it automatically goes to members of the association before they are offered for sale in the ASCD catalog.

Marshall, who currently serves as associate dean for research and graduate studies in Clemson’s College of Education, knows from experience that the brightest students are often just as hard to keep engaged in the classroom as those who struggle. They’re naturally adept at playing “the game of school,” as Marshall puts it. They quickly find out what their teacher needs to give them a good grade, and they satisfy those requirements. Once they learn to game the system, there’s little reason to keep playing and no real reason to challenge themselves. On the other end of the spectrum, there are students who have too much trouble with material and start to tune out.

He says one of the book’s primary goals is to reveal the most effective kind of rigor to add to a classroom for different audiences. Marshall says he has forged a good relationship with ASCD because his books are based in research but aimed at providing practical applications to teachers.

“Far too often teachers think that rigor just means handing out more worksheets to students,” Marshall says. “Challenge in the classroom is directly linked to student achievement, and that’s for students of all ability levels.”

Marshall does not support grouping or sorting students based on ability level because he doesn’t feel that it prepares them for the real world where adults of many different skill levels must work together. When an educator asks Marshall how they can serve so many different types of learners at once, Marshall asks them to picture a chalk board with only one math problem.

“Why’s there only one? Why aren’t there three different problems?” Marshall asks. “Provide a problem so challenging that only a few can get it, and if they can’t they move to the next one or they team up with a friend to try to solve the hardest one. That’s when learning happens; it certainly doesn’t happen because of rote memorization.”

Through his work as a professional development consultant and author, Marshall seeks to help educators start seeing the development of all learners—the ones who are naturally good at the game of school and those who aren’t—as their own personal challenge.

The answer is often introducing challenge, and more importantly introducing failure as an option. Marshall says the concepts of multiple right answers or no answer at all better prepare students for the real world.

“We bubble wrap our students, and we’re finding ourselves as a society to be more and more anxious all the time,” Marshall says. “I think some of that comes from being told there’s one safe, correct answer. When educators effectively challenge their students, they’re teaching them to learn from failure and that struggling through things is healthy.”

END

Get in touch and we will connect you with the author or another expert.

Or email us at news@clemson.edu